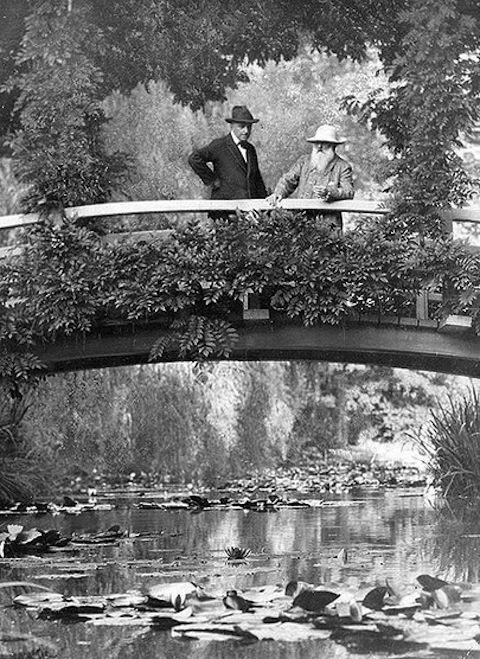

What could be more charmingly idyllic than a glimpse of snowy-bearded Impressionist Claude Monet calmly painting en plein-air in his garden at Giverny?

A wide-brimmed hat and two luxuriously large patio-type umbrellas provide shade, while the artist stays cool in a pristine white suit.

His canvas is off camera for the most part, but given the coordinates, it seems safe to assume the subject’s got something to do with the famous Japanese footbridge spanning Monet’s equally famous lily pond.

The sun’s still high when he puts down his cat’s tongue brush and heads back to the house with his little dog at his heels, no doubt anticipating a delicious, relaxed luncheon.

Even in black-and-white, it’s an irresistible pastoral vision!

And quite a contrast to the recent scene some 300 km away in Ypres, where German troops weaponized chlorine gas for the first time, releasing it in the Allied trenches the same year the above footage of Monet was shot.

Lendon Payne, a British sapper, was an eyewitness to some of the mayhem:

When the gas attack was over and the all clear was sounded I decided to go out for a breath of fresh air and see what was happening. But I could hardly believe my eyes when I looked along the bank. The bank was absolutely covered with bodies of gassed men. Must have been over 1,000 of them. And down in the stream, a little bit further along the canal bank, the stream there was also full of bodies as well. They were gradually gathered up and all put in a huge pile after being identified in a place called Hospital Farm on the left of Ypres. And whilst they were in there the ADMS came along to make his report and whilst he was sizing up the situation a shell burst and killed him.

The early days of the Great War are what spurred director Sacha Guitry, seen chatting with Monet above, to visit the 82-year-old artist as part of his 22-minute silent documentary, Ceux de Chez Nous (Those of Our Land).

The entire project was an act of resistance.

With German intellectuals trumpeting the superiority of Germanic culture, the Russian-born Guitry, a successful actor and playwright, sought out audiences with aging French luminaries, to preserve for future generations.

In addition to Monet, these include appearances by painters Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas, sculptor Auguste Rodin, writer Anatole France, composer Camille Saint-Saens, and actor Sarah Bernhardt.

Although Ceux de Chez Nous was silent, Guitry carefully documented the content of each interview, revisiting them in 1952 for the expanded version with commentary, below.

Beneath his placid exterior, Monet, too, was quite consumed by the horrors unfolding nearby.

James Payne, creator of the web series Great Art Explained, views Monet’s final eight water lily paintings as a “direct response to the most savage and apocalyptic period of modern history…a war memorial to the millions of lives tragically lost in the First World War.”

In 1914, Monet wrote that while painting helped take his mind off “these sad times” he also felt “ashamed to think about my little researches into form and colour while so many people are suffering and dying for us.”

As curator Ann Dumas notes in RA Magazine:

The peace of his garden was sometimes shattered by the sound of gunfire from the battlefields only 50 kilometres away. His stepson was fighting at the front and his own son Michel was called up in 1915. Many of the inhabitants of Giverny fled to safety but Monet stayed behind: “…if those savages must kill me, it will be in the middle of my canvases, in front of all my life’s work.” Painting was what he did and he saw it, in a way, as his patriotic contribution. A group of paintings of the weeping willow, a traditional symbol of mourning, was Monet’s most immediate response to the war, the tree’s long, sweeping branches hanging over the water, an eloquent expression of grief and loss.

Related Content

1540 Monet Paintings in a Two Hour Video

Why Monet Painted The Same Haystacks 25 Times

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.