That vast repository of American history that is the Smithsonian Institution evolved from an organization founded in 1816 called the Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences. Its mandate, the collection and dissemination of useful knowledge, now sounds very much of the nineteenth century — but then, so does its name. Columbia, the goddess-like symbolic personification of the United States of America, is seldom directly referenced today, having been superseded by Lady Liberty. Traits of both figures appear in the depiction on the nineteenth-century fireman’s hat above, about which you can learn more at Smithsonian Open Access, a digital archive that now contains some 4.5 million images.

“Anyone can download, reuse, and remix these images at any time — for free under the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license,” write My Modern Met’s Jessica Stewart and Madeleine Muzdakis. “A dive into the 3D records shows everything from CAD models of the Apollo 11 command module to Horatio Greenough’s 1840 sculpture of George Washington.”

The 2D artifacts of interest include “a portrait of Pocahontas in the National Portrait Gallery, an image of the 1903 Wright Flyer from the National Air and Space Museum, and boxing headgear worn by Muhammad Ali from the National Museum of African American History and Culture.”

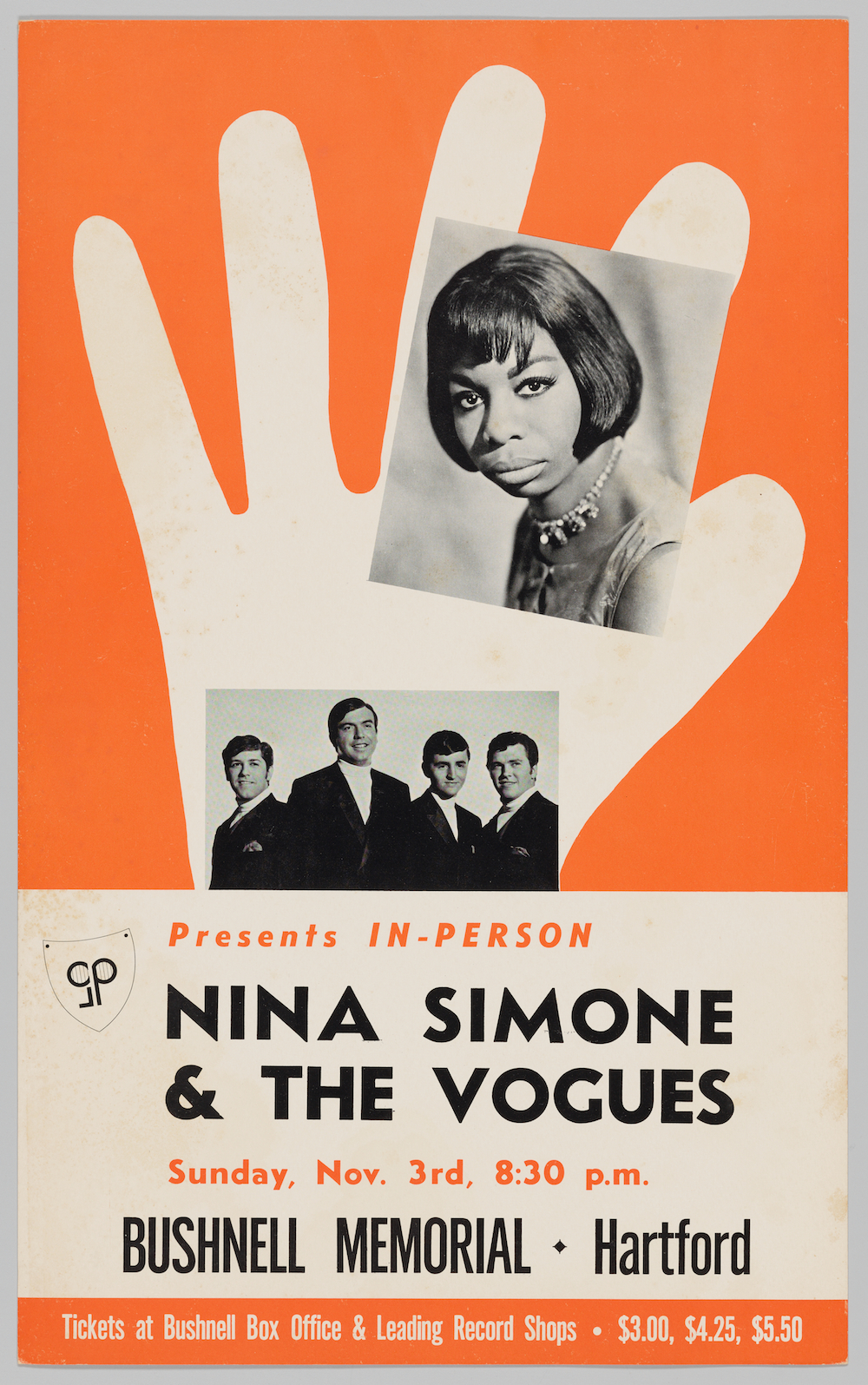

The NMAAHC in particular has provided a great many items relevant to twentieth-century American culture, like James Baldwin’s inkwell, Chuck Berry’s guitar Maybellene, Public Enemy’s boombox, and the poster for a 1968 Nina Simone concert. The more obscure object just above, a Native American kachina figure with the head of Mickey Mouse, comes from the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “When Disney Studios put a mouse hero on the silver screen in the 1930s,” explain the accompanying notes, “Hopi artists saw in Mickey Mouse a celebration of Tusan Homichi, the legendary mouse warrior who defeated a chicken-stealing hawk” — and were thus themselves inspired, it seems, to sum up a wide swath of American history in a single object.

More items are being added to Smithsonian Open Access all the time, each with its own story to tell — and all accessible not just to Americans, but internet users the world over. In that sense it feels a bit like the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, better known as the World’s Columbian Exposition, with its mission of revealing America’s scientific, technological, and artistic genius to the whole of human civilization. You can see a great many photos and other artifacts of this landmark event at Smithsonian Open Access, or, if you prefer, you can click the “just browsing” link and behold all the historical, cultural, and formal variety available in the Smithsonian’s digital collections, where the spirit of Columbia lives on.

Related content:

Why 99% Of Smithsonian’s Specimens Are Hidden In High Security

John Green’s Crash Course in U.S. History: From Colonialism to Obama in 47 Videos

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.