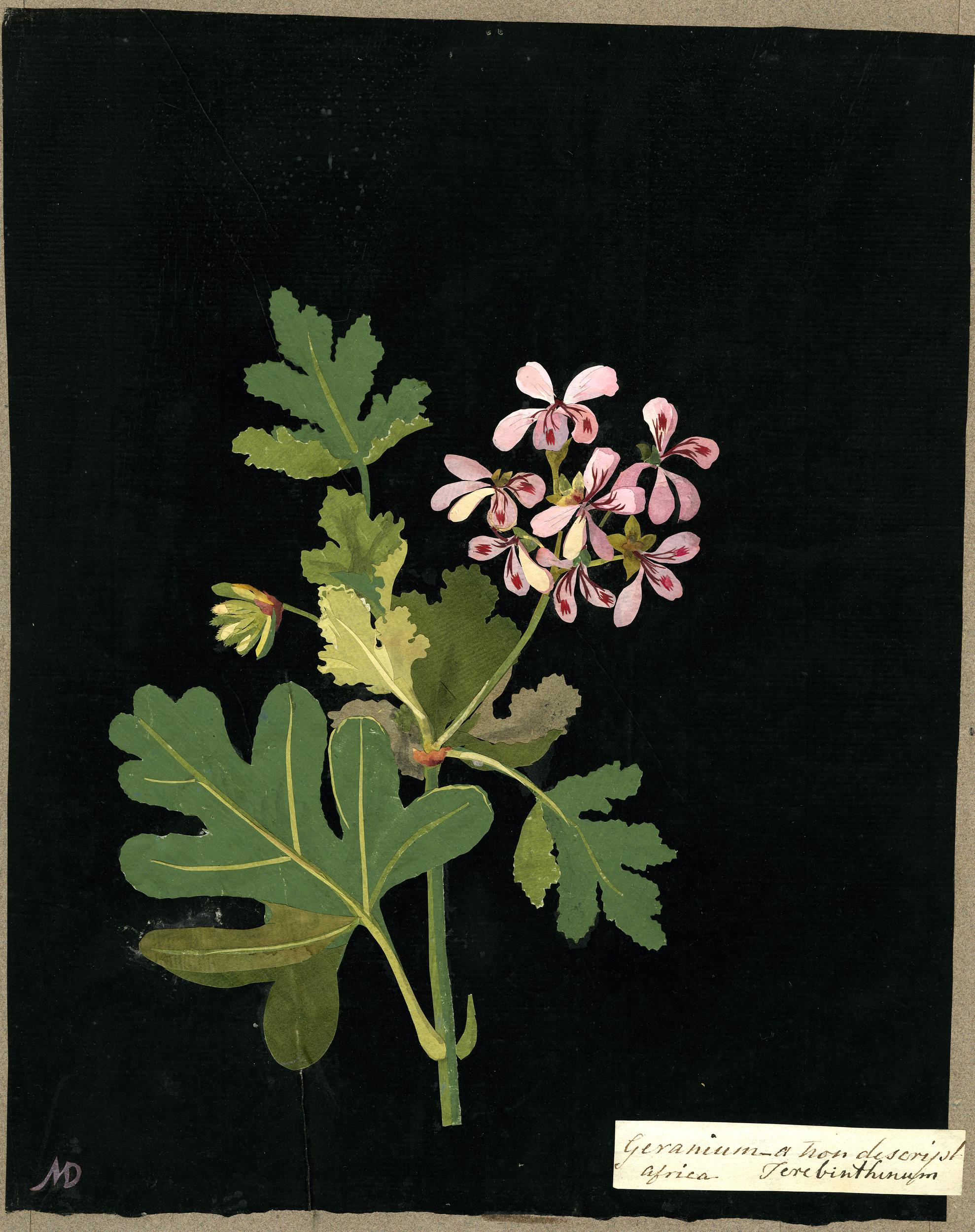

“I have invented a new way of imitating flowers,” Mary Delany, a 72-year-old widow wrote to her niece in 1772 from the grand home where she was a frequent guest, having just captured her hostess’ geranium’s likeness, by collaging cut paper in a nearly identical shade.

Novelty rekindled the creative fire her husband’s death had dampened.

Former pursuits such as needlework, silhouette cut outs, and shell decorating went by the wayside as she dedicated herself fully to her botanical-themed “paper mosaicks.”

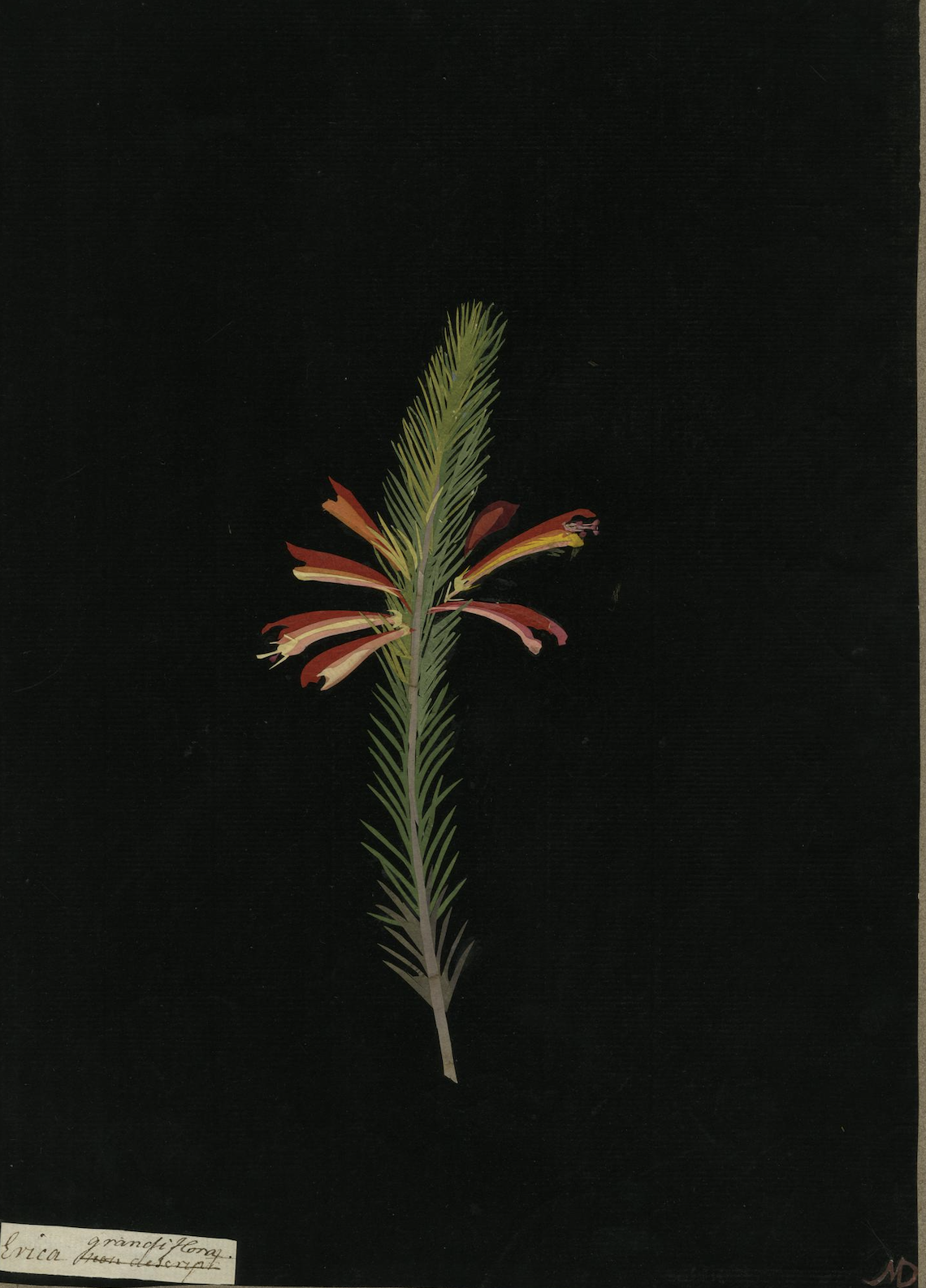

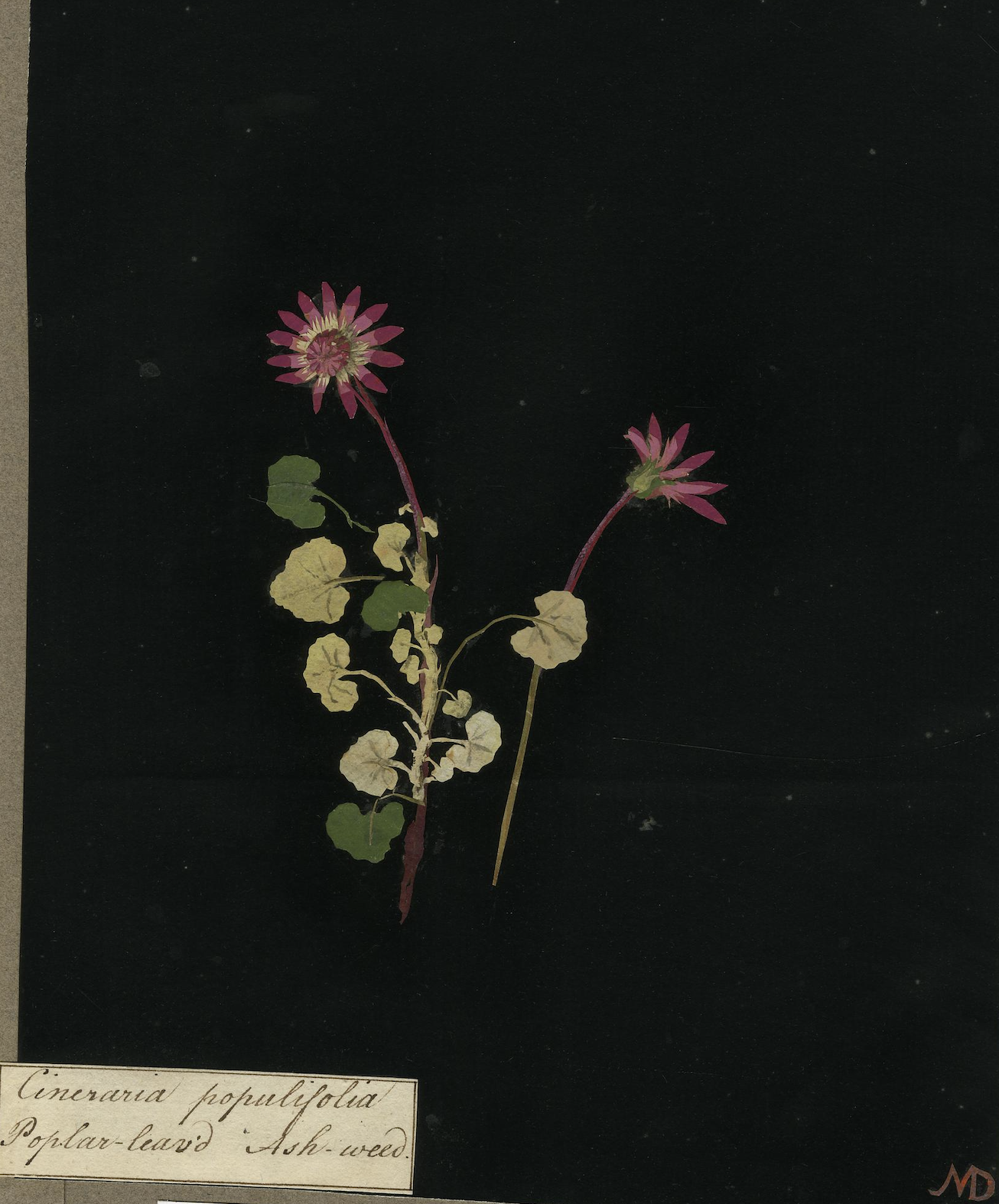

Over the next decade Mrs. Delany produced 985 astonishingly floral representations from meticulously cut, hand colored tissue, which she glued to hand painted black backings, and labeled with the specimens’ taxonomic and common names, as well as a collection of numbers, date and provenance.

In the beginning, she took inspiration from a giant collection of botanical specimens amassed by the celebrated botanist Sir Joseph Banks, with whom she became acquainted while spending summers at Bulstrode, the Buckinghamshire estate of her friend Margaret Bentinck, duchess of Portland and a fellow enthusiast of the natural world.

Bulstrode also provided her with abundant source material. The estate boasted botanic, flower, kitchen, ancient and American gardens, as well a staff botanist, the Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander charged with cataloguing their contents according to the Linnaean system.

Sir Joseph Banks commended Mrs. Delany’s powers of observation, declaring her assemblages “the only imitations of nature” from which he “could venture to describe botanically any plant without the least fear of committing an error.”

They also succeed as art.

Molly Peacock, author of The Paper Garden: An Artist Begins Her Life’s Work at 72, appears quite overcome by Mrs. Delany’s Passiflora laurifolia — more commonly known as water lemon, Jamaican honeysuckle or vinegar pear:

The main flower head … is so intensely public that it’s as if you’ve come upon a nude stody. She splays out approximately 230 shockingly vulvular purplish pink petals in the bloom, and inside the leaves she places the slenderest of ivory veins also cut separately from paper, with vine tendrils finer that a girl’s hair. It is so fresh that it looks wet and full of desire, yet the Passiflora is dull and matte

Mrs. Delany’s exquisitely rendered paper flowers became high society sensations, fetching her no small amount of invitations from titled hosts and hostesses, clamoring for specimens from their gardens to be immortalized in her growing Flora Delanica.

She also received donations of exotic plants at Balstrode, where greenhouses kept non-native plants alive, as she gleefully informed her niece in a 1777 letter, shortly after completing her work:

I am so plentifully supplied with the hothouse here, and from the Queen’s garden at Kew, that natural plants have been a good deal laid aside this year for foreigners, but not less in favour. O! How I long to show you the progress I have made.

Her work was in such demand, that she streamlined her creation process from necessity, coloring paper in batches, and working on several pieces simultaneously.

Her failing eyesight forced her to stop just shy of her goal of one thousand flowers.

She dedicated the ten volumes of Flora Delanica to her friend, the duchess of Portland, mistress of Balstrode “(whose) approbation was such a sanction to my undertaking, as made it appear of consequence and gave me courage to go on with confidence.”

She also reflected on the great undertaking of her seventh decade in a poem:

Hail to the happy hour! When fancy led

My pensive mind this flow’ry path to tread;

And gave me emulation to presume

With timid art to trace fair Nature’s bloom.

Explore The British Museum’s interactive archive of Mary Delany’s botanical paper collages here.

All images © The Trustees of the British Museum, republished under a Creative Commons license.

Related Content

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

A Beautiful 1897 Illustrated Book Shows How Flowers Become Art Nouveau Designs

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.