CBGB is a state of mind — Patti Smith

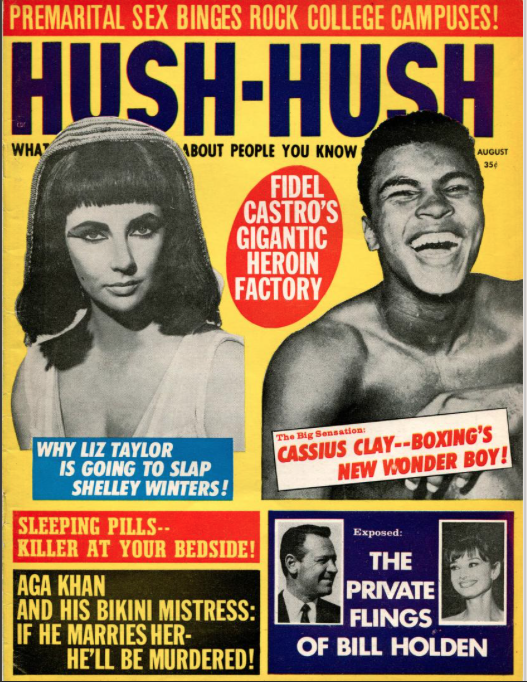

All good things must come to an end, but it hurt when CBGB’s, New York City’s celebrated — and famously filthy — music club shuttered for good on October 15th, 2006, a victim of skyrocketing Lower East Side rents.

While plenty of punk and New Wave luminaries cut their teeth on the legendary venue’s stage — Talking Heads, The Ramones, Blondie — final honors went to Patti Smith, a CBGB’s habitué, whose seven-week residency in 1975 earned her a major record deal.

In her National Book Award-winning memoir, Just Kids, Smith described her first impressions of the place, when she and her guitarist Lenny Kaye headed downtown to catch their friend Richard Hell’s band, Television, following the premiere of the concert film, Ladies & Gentlemen, the Rolling Stones at the Ziegfeld:

CBGB was a deep and narrow room along the right side, lit by overhanging neon signs advertising various brands of beer. The stage was low, on the left-hand side, flanked by photographic murals of turn-of-the-century bathing belles. Past the stage was a pool table, and in back was a greasy kitchen and a room where the owner, Hilly Krystal, worked and slept with his saluki, Jonathan…

It was a world away from the Ziegfeld. The absence of glamour made it seem all the more familiar, a place that we could call our own. As the band played on, you could hear the whack of the pool cue hitting the balls, the saluki barking, bottles clinking, the sounds of a scene emerging. Though no one knew it, the stars were aligning, the angels were calling.

Some 30 years later, Kaye prepared to bid CBGB goodbye, telling the New York Times, “It’s like it’s grown its own barnacles:”

You couldn’t replicate the décor in a million years, and dismantling all those layers of archaeology of music in the club is a daunting task.

The Village Voice observed that it was “a crazy, emotional night for everyone in the crowd and for everyone on the stage,” and the New York Times reported how Smith documented the club’s awning with a Polaroid, explaining, “I’m sentimental…”

But Smith, who actively encouraged young fans to resist worshiping at the altar of the club’s reputation when they could be starting scenes of their own, also pushed back against sentimentality, telling the crowd, “It’s not a fucking temple — it is what it is.”

That may be, but her three-and-a-half-hour performance, above, was still one for the history books, from the opening reading of Piss Factory (I’m gonna be somebody, I’m gonna get on that train, go to New York City /I’m gonna be so bad I’m gonna be a big star and I will never return) to the closing in memoriam recitation (Joe Strummer…Johnny Thunders…Stiv Bators…Johnny, Joey, and Dee Dee Ramone…)

Smith took care that other artists who helped make the scene were represented in her below set lists, from Blondie and Lou Reed to Television and the Dead Boys:

Piss Factory 0:22

Kimberly/Tide is High 12:40

Pale Blue Eyes 20:30

Lou (Reed) had a gift of taking very simple lines, ‘Linger on, your pale blue eyes,’ and make it so they magnify on their own. That song has always haunted me. (The Associated Press)

Marquee Moon/We Three 29:02

Television will help wipe out media. They are not theatre. Neither were the early Stones or the Yardbirds. They are strong images procduce from pain and speed and the fanatic desire to make it. They are also inspired enough below the belt to prove that SEX is not dead in rock ’n’ roll. (Rock Scene)

Distant Fingers 38:48

Without Chains 47:50

We had emotional duties, and I respected that. But I also thought it was important to do a song like that. (Rolling Stone)

Ghost Dance 55:30

Birdland 1:00:08

Sonic Reducer 1:11:52

Redondo Beach 1:16:00

Free Money 1:20:44

Pissing in a River 1:28:27

Gimme Shelter 1:33:50

I was thinking about the words to that: “War, children, it’s just a shot away.” To me, a song like that is more meaningful than ever. (Rolling Stone)

Space Monkey 1:43

Blitzkrieg Bop / Beat on the Brat / Do You Remember Rock ‘N’ Roll Radio? / Sheena Is a Punk Rocker 1:48:30

Ain’t It Strange 1:55:20

So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star 2:02:11

Babelogue/Rock n Roll N — - — - — - 2:10:17

Happy Birthday to Flea 2:21:38

For Your Love 2:22:15

My Generation 2:27:22

Land/Gloria 2:36:51

Even though I wrote the poem at the beginning of “Gloria” in 1970, it took all those years to evolve, to merge into “Gloria.” And that was pretty much done at CBGB. We recorded Horses in 1975, and did all the groundwork at CBGB. (Rolling Stone)

Elegie 2:55:57

As I was reading that little list, those people seemed in that moment — because of the intense emotional energy in that room — to be alive. Everyone in the room knew or heard of or loved one of those people. That collective love and sorrow and recognition made those people seem as alive as any of us. (Rolling Stone)

Related Content

Patti Smith Plays at CBGB In One of Her First Recorded Concerts, Joined by Seminal Punk Band Television (1975)

NYC’s Iconic Punk Club CBGBs Comes Alive in a Brilliant Short Animation, Using David Godlis’ Photos of Patti Smith, The Ramones & More

Beautiful New Photo Book Documents Patti Smith’s Breakthrough Years in Music: Features Hundreds of Unseen Photographs

Patti Smith’s 40 Favorite Books

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.