Many of us avoid turning on the oven during a heatwave, but how do we feel about making cookies in a Dutch Oven heaped with glowing embers?

Justine Dorn, co-creator with other half, Ron Rayfield, of the Early American YouTube channel, strives to recreate 18th and early 19th century desserts in an authentic fashion, and if that means whisking egg whites by hand in a 100 degree room, so be it.

“Maybe hotter,” she wrote in a recent Instagram post, adding:

It’s hard work but still I love what I do. I hope that everyone can experience the feeling of being where you belong and doing what you know you were born to do. Maybe not everyone will understand your reasoning but if you are comfortable and happy doing what you do then continue.

Her historic labors have an epic quality, but the recipes from aged cookbooks are rarely complex.

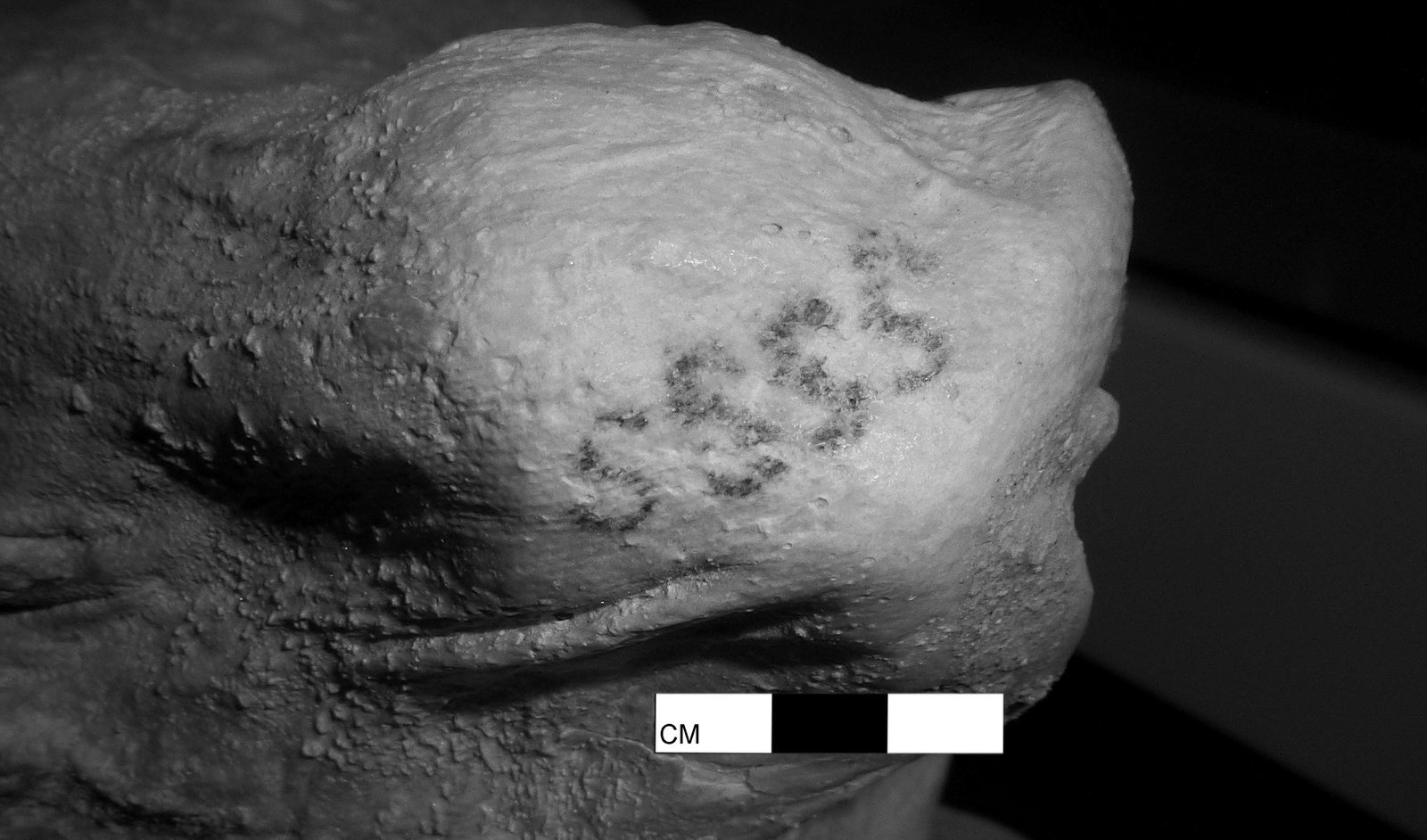

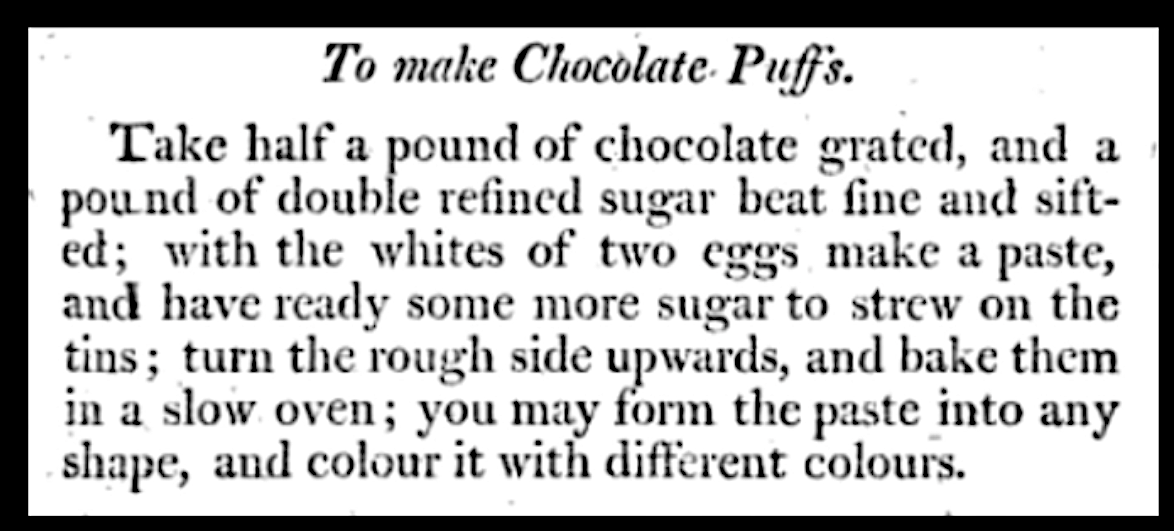

The gluten free chocolate cookies from the 1800 edition of The Complete Confectioner have but three ingredients — grated chocolate, caster sugar, and the aforementioned egg whites — cooked low and slow on parchment, to create a hollow center and crispy, macaron-like exterior.

Unlike many YouTube chefs, Dorn doesn’t translate measurements for a modern audience or keep things moving with busy editing and bright commentary.

Her silent, lightly subtitled approach lays claim to a previously unexplored corner of autonomous sensory meridian response — ASMR Historical Cooking.

The sounds of crackling hearth, eggs being cracked into a bowl, hot embers being scraped up with a metal shovel turn out to be compelling stuff.

So were the cookies, referred to as “Chocolate Puffs” in the original recipe.

Dorn and Rayfield have a secondary channel, Frontier Parrot, on which they grant themselves permission to respond verbally, in 21st century vernacular, albeit while remaining dressed in 1820s Missouri garb.

“I would pay a man $20 to eat this whole plate of cookies because these are the sweetest cookies I’ve ever come across in my life,” Dorn tells Rayfield on the Frontier Parrot Chat and Chew episode, below. “They only have three ingredients, but if you eat more than one you feel like you’re going to go into a coma — a sugar coma!”

He asserts that two’s his limit and also that they “sound like hard glass” when knocked against the table.

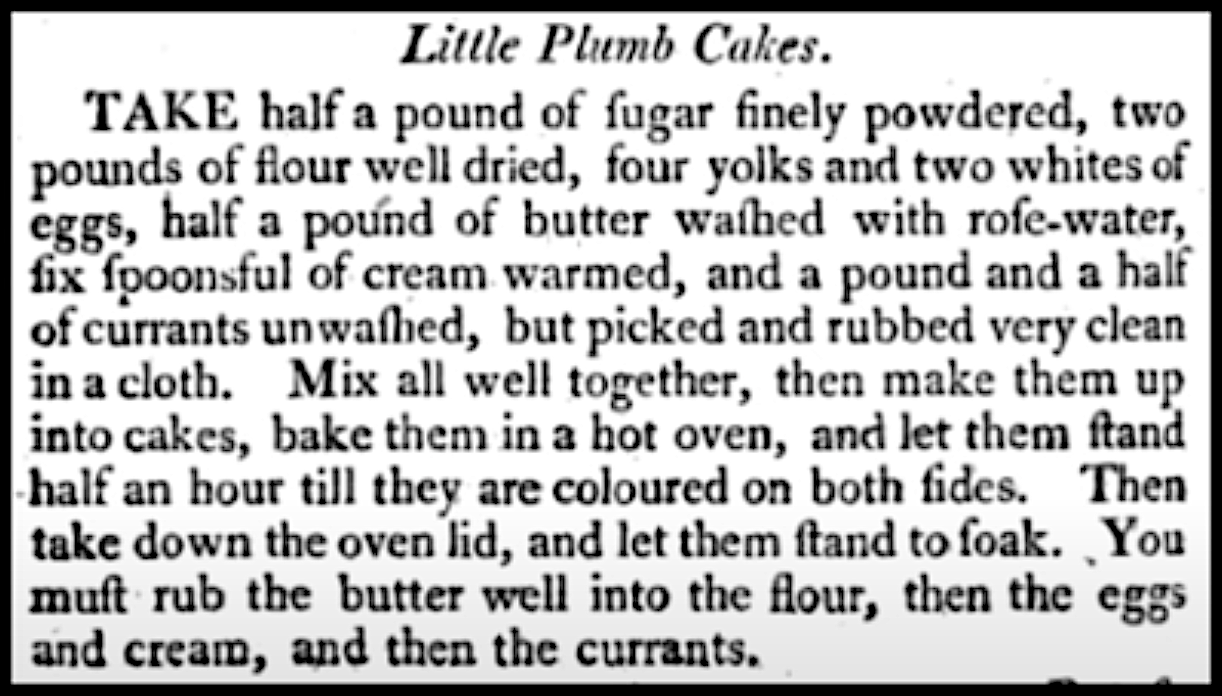

Early Americans would have gaped at the indulgence on display above, wherein Dorn whips up not one but three cake recipes in the space of a single episode.

The plum cakes from the Housekeeper’s Instructor (1791) are frosted with an icing that Rayfield identifies on a solo Frontier Parrot as 2 cups of sugar whipped with a single egg white.

“We suffered for this icing,” Dorn revealed in an Instagram post. “SUFFERED. Ya’ll don’t know true pain until you whip icing from hand using only egg whites and sugar.”

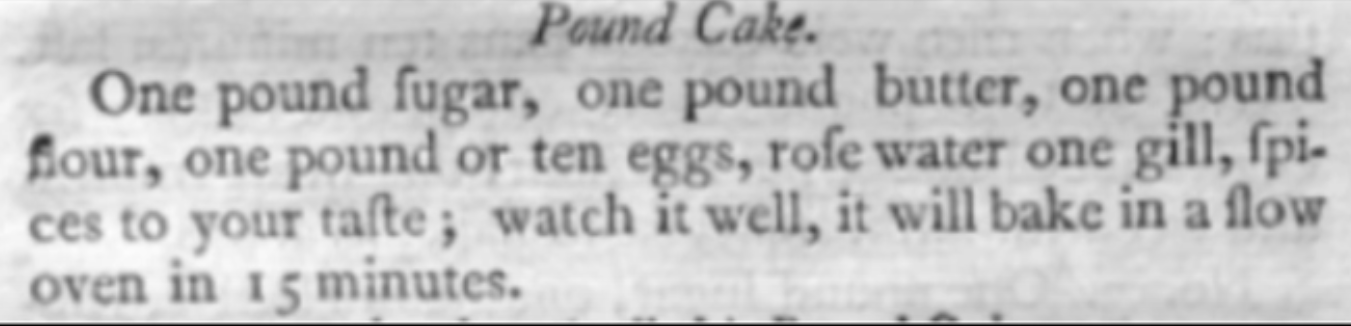

The flat little pound cakes from 1796’s American Cookery call for butter rubbed with rosewater.

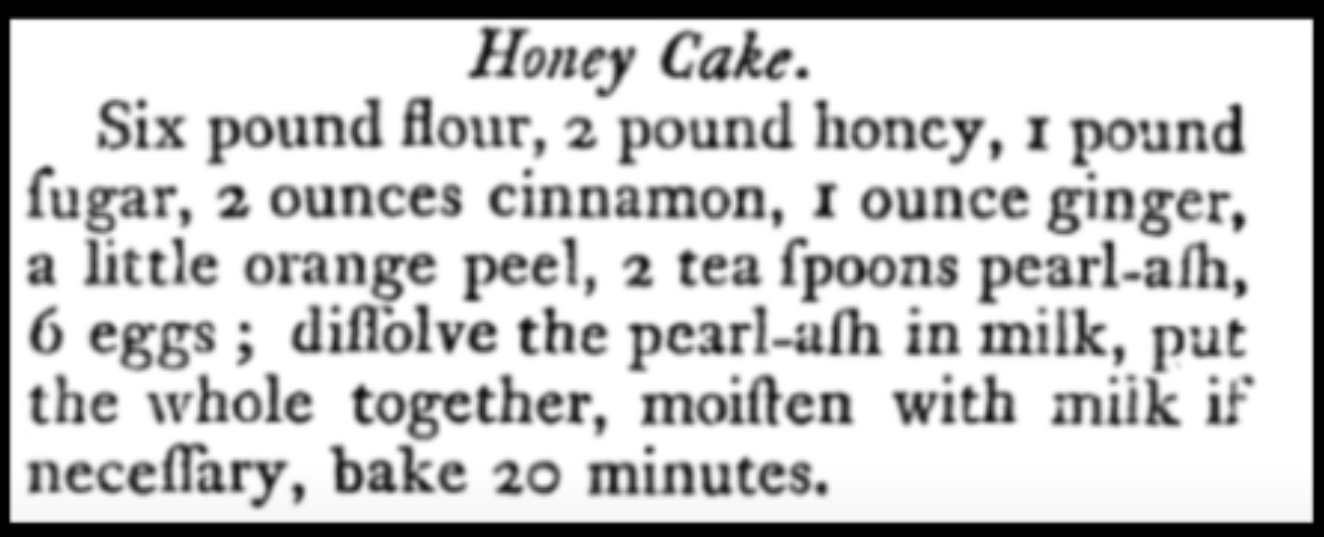

The honey cake from American Domestic Cookery, Formed on Principles of Economy, For the Use of Private Families (1871), gets a lift from pearl ash or “potash”, a German leavening agent that’s been rendered virtually obsolete by baking powder.

Those who insist on keeping their ovens off in summer should take a moment to let the title of the below episode sink in:

Making Ice Cream in the 1820s SUCKS. “

This dish doesn’t call for blood, sweat and tears,” Dorn writes of the pre-Victorian, crank-free experience, “but we’re gonna add some anyway.”

Find a playlist of Dorn’s Early American dessert reconstructions, including an amazing cherry raspberry pie and a cheap seed cake here.

Related Content

Thomas Jefferson’s Handwritten Vanilla Ice Cream Recipe

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.