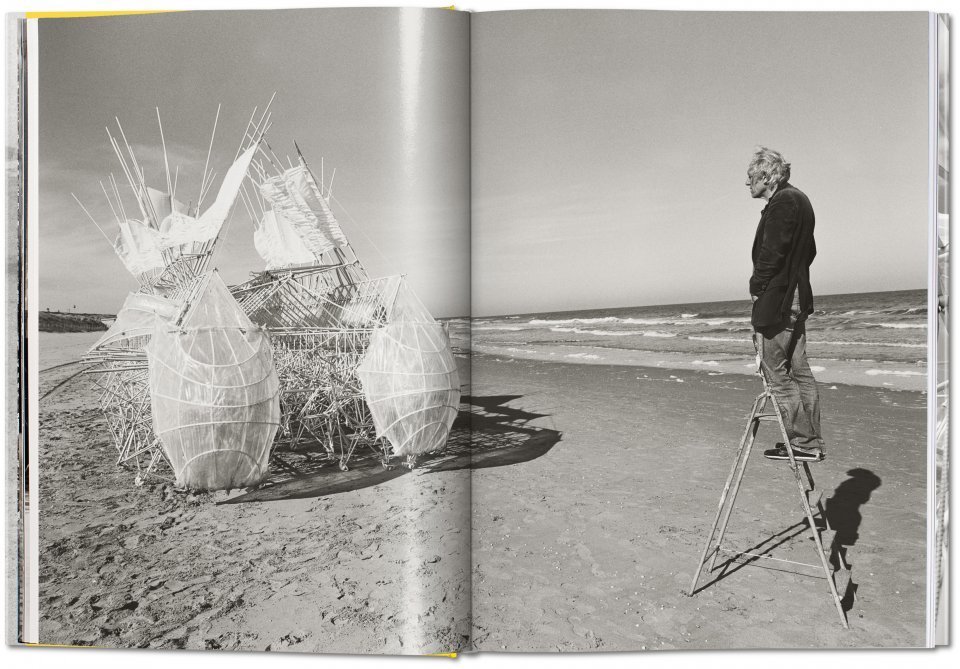

110 years after its first and last voyage, we remember the RMS Titanic and its touted “unsinkability” as one of the resounding ironies of maritime history. But 1912 also saw the launch of another newly built yet ill-fated ship whose name proved all too apt: Endurance, as it was rechristened by Sir Ernest Shackleton when he purchased it to use on his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914. In January of the following year, Endurance got stuck in the ice of the Weddell Sea off Antarctica, and over the following ten months that ice slowly crushed and ultimately sank the ship. But her whole crew survived, thanks to Shackleton’s leading them more than 800 miles over the open ocean to safety.

Shackleton and his men have been celebrated for their endurance; as for Endurance herself, it has spent more than a century unseen at the bottom of the ocean — unseen, that is, until now. “A team of adventurers, marine archaeologists and technicians located the wreck at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, east of the Antarctic Peninsula, using undersea drones,” writes the New York Times’ Henry Fountain. “Battling sea ice and freezing temperatures, the team had been searching for more than two weeks in a 150-square-mile area around where the ship went down in 1915.”

Time turns out to have been kind to Shackleton’s ship: “Endurance’s relatively pristine appearance was not unexpected, given the cold water and the lack of wood-eating marine organisms in the Weddell Sea that have ravaged shipwrecks elsewhere.” You can glimpse Endurance in her watery grave in the Marine Technology TV video at the top of the post. But you’ll also see a lot more of another impressive ship: Agulhas II, the South African icebreaker used by Endurance22, as the $10 million research expedition was called. Whatever the challenges posed by finally tracking down Endurance, their brunt wasn’t borne by that mighty vessel.

“Aside from a few technical glitches involving the two submersibles, and part of a day spent icebound when operations were suspended, the search proceeded relatively smoothly,” reports Fountain. The nature of this expedition, especially in its use of submersibles to observe the wreckage without disturbing it, may bring back to mind (for those of us of a certain age) the 1992 documentary Titanica, which astonished us with the first up-close, IMAX-sized views of the sunken Titanic. Considering the advancements in exploratory and photographic technology in the three decades since — and the condition of Endurance itself — the film that eventually results from Endurance22 should astonish us all over again.

For anyone interested in Shackleton’s remarkable adventure, we recommend the book The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition.

Related content:

Hear Ernest Shackleton Speak About His Antarctic Expedition in a Rare 1909 Recording

Google Street View Opens Up a Look at Shackleton’s Antarctic

How the Titanic Sank: James Cameron’s New CGI Animation

The Titanic: Rare Footage of the Ship Before Disaster Strikes (1911–1912)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.