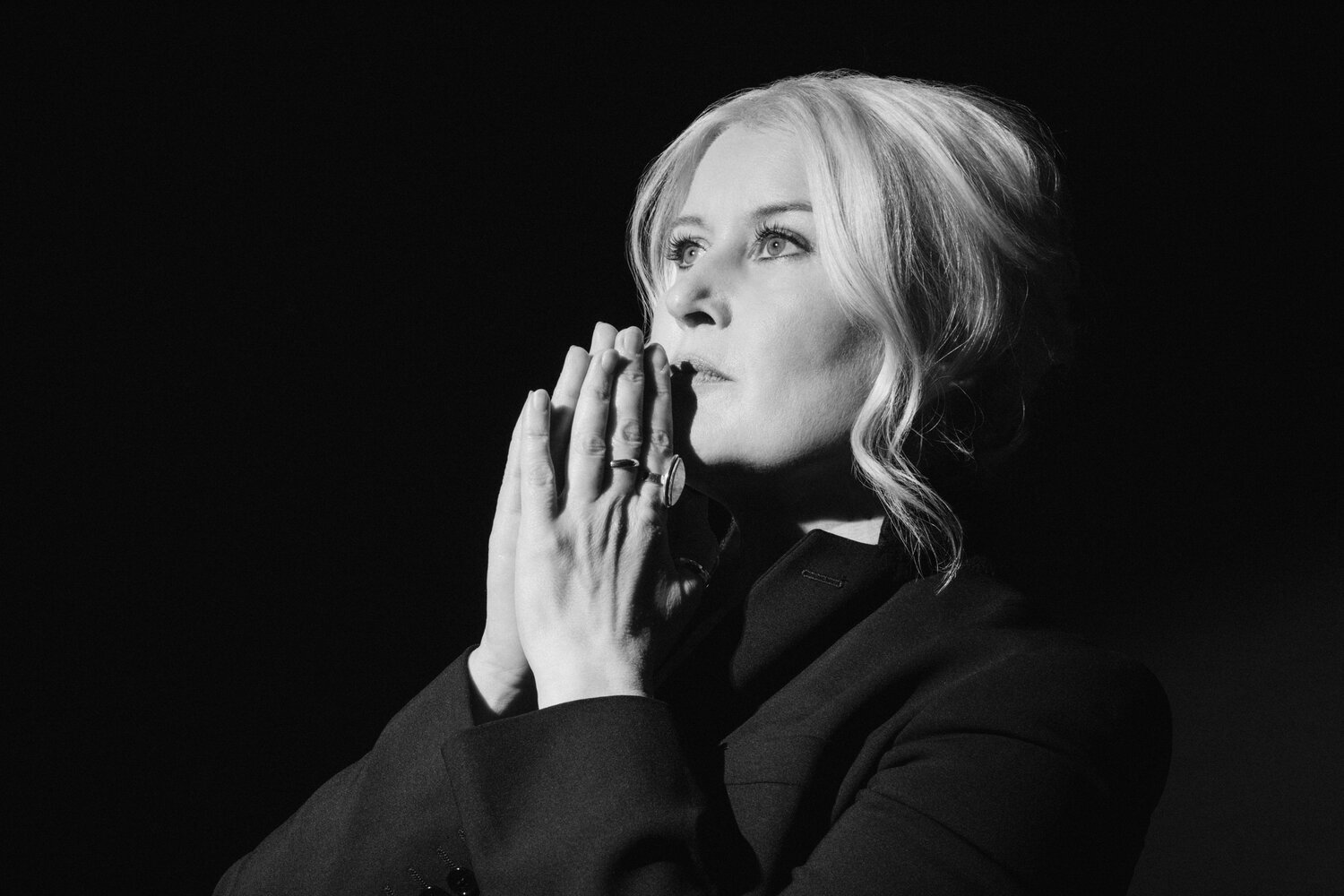

Actress Eartha Kitt amassed dozens of stage and screen credits, but is perhaps most fondly remembered for her iconic turn as Catwoman in the Batman TV series, a role she took over from white actress Julie Newmar.

The producers congratulated themselves on this “provocative, off-beat” casting, executives at network affiliates in Southern states expressed outrage, and Kitt’s 9‑year-old daughter, Kitt Shapiro, understood that her mother’s new gig was a “really big deal.”

As Shapiro recalled to Closer Weekly:

This was 1967, and there were no women of color at that time wearing skintight bodysuits, playing opposite a white male with sexual tension between them! She knew the importance of the role and she was proud of it. She really is a part of history. She was one of the first really beautiful black women — her, Lena Horne, Dorothy Dandridge — who were allowed to be sexy without being stereotyped. It does take a village, but I do think she helped blaze a trail.

Eartha Kitt was a trailblazer in other ways too.

Catwoman vs. the White House, director Scott Calonico’s short documentary for the New Yorker (above), uses vintage photos, clippings and footage to relate how Kitt disrupted a White House luncheon the month after her Batman debut, taking President Lyndon B. Johnson to task over the hardships faced by working parents.

Johnson was clearly under the impression that he was swinging by the White House Family Dining Room as a favor to his wife, Lady Bird, who was hosting 50 guests for the Women Doers’ Luncheon. The theme of the luncheon was “What Citizens Can Do to Help Insure Safe Streets.”

Chairman of the National Council on the Arts Roger Stevens had suggested that Kitt or actress Ruby Dee would be fine additions to the guest list in recognition for their activism with urban youth.

As Janet Mezzack details in her Presidential Studies Quarterly article, “Without Manners You Are Nothing”: Lady Bird Johnson, Eartha Kitt, and The Women Doers’ Luncheon of January 18, 1968, Kitt had an impressive track record of volunteerism.

She taught dance to Black children who could not afford lessons, testified before the House General Subcommittee on Education on behalf of the DC youth-led Rebels with a Cause, and established a non-profit organization in Watts where underprivileged youth studied traditional African and modern dance and “learned about personality development, poise, grooming, diction, and physical fitness.”

She was being vetted for a seat on President Johnson’s Citizens Advisory Board on Youth Opportunity, chaired by Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

Surely, a dream guest!

Mezzack writes:

Having selected Kitt as a guest for the upcoming luncheon, FBI clearance checks were conducted on her and other prospective guests at the White House. The FBI cleared her through normal channels. Because of previous embarrassing situations involving entertainers invited to White House functions, inquiries also were made of Roger Stevens office to determine if Kitt would “do anything to embarrass” the White House, “and the answer was no.”

Call it embarrassment for a good cause.

Johnson was unprepared for spontaneous interaction as hard hitting as Kitt’s, when she stood up to say:

Mr. President, you asked about delinquency across the United States, which we are all interested in and that’s why we’re here today. But what do we do about delinquent parents? The parents who have to go to work, for instance, who can’t spend the time with their children that they should. This is, I think, our main problem. What do we do with the children then, when the parents are off working?

Fumbling for an answer, Johnson intimated that the male policymakers behind recent Social Security Amendments that could offset costs of daycare were “really not the best judges of how to handle children.”

Perhaps Miss Kitt would like to take her concerns with the other women in attendance?

Understandably, Kitt seethed, and continued the conversation by confronting the First Lady over the war in Vietnam.

Director Calonico toggles between Kitt’s recollections of the exchange and excerpts from Mrs. Johnson’s White House audio diary, cobbling together a reconstruction that is surely faithful to the spirit of the thing, if not exactly word for word:

Kitt’s words as recalled by Mrs. Johnson:

You send the best in this country off to be shot and maimed. They rebel in the street. They will take pot and get high. They don’t want to go to school because they’re going to be snatched off from their mothers to be shot in Vietnam.

Kitt’s words as recalled by the speaker herself:

Mrs. Johnson, you are a mother too, although you have had daughters and not sons. I am a mother and I know the feeling of having a baby come out of my gut. I have a baby and then you send him off to war. No wonder the kids rebel and take pot, and Mrs. Johnson, in case you don’t understand the lingo, that’s marijuana.

That last comment seems funny now, and Calanico can’t resist infusing further dark humor with a shot of a masked Kitt tooling around in Catwoman’s campy Kittycar as the actress describes how the White House cancelled her ride home from the luncheon.

The next day’s newspapers were full of emotionally charged reports as to how Kitt’s remarks had left the hostess “stunned to tears” — a description both participants resisted.

Within weeks, North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive, and Johnson announced he would not seek reelection.

Meanwhile Kitt’s outspokenness at the luncheon cast an instantaneous chill on her career, stateside.

She spent the next decade performing in Europe, unaware that the CIA had opened a file on her, compiling information from confidential sources in Paris and New York City as to her “loose morals.”

Her response to the most outrageous allegations in that file should make lifelong fans of feminists who were barely out of diapers when Halle Berry slipped into Catwoman’s skintight pajamas.

Calonico is right to punctuate this with Kitt’s triumphant growl.

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.