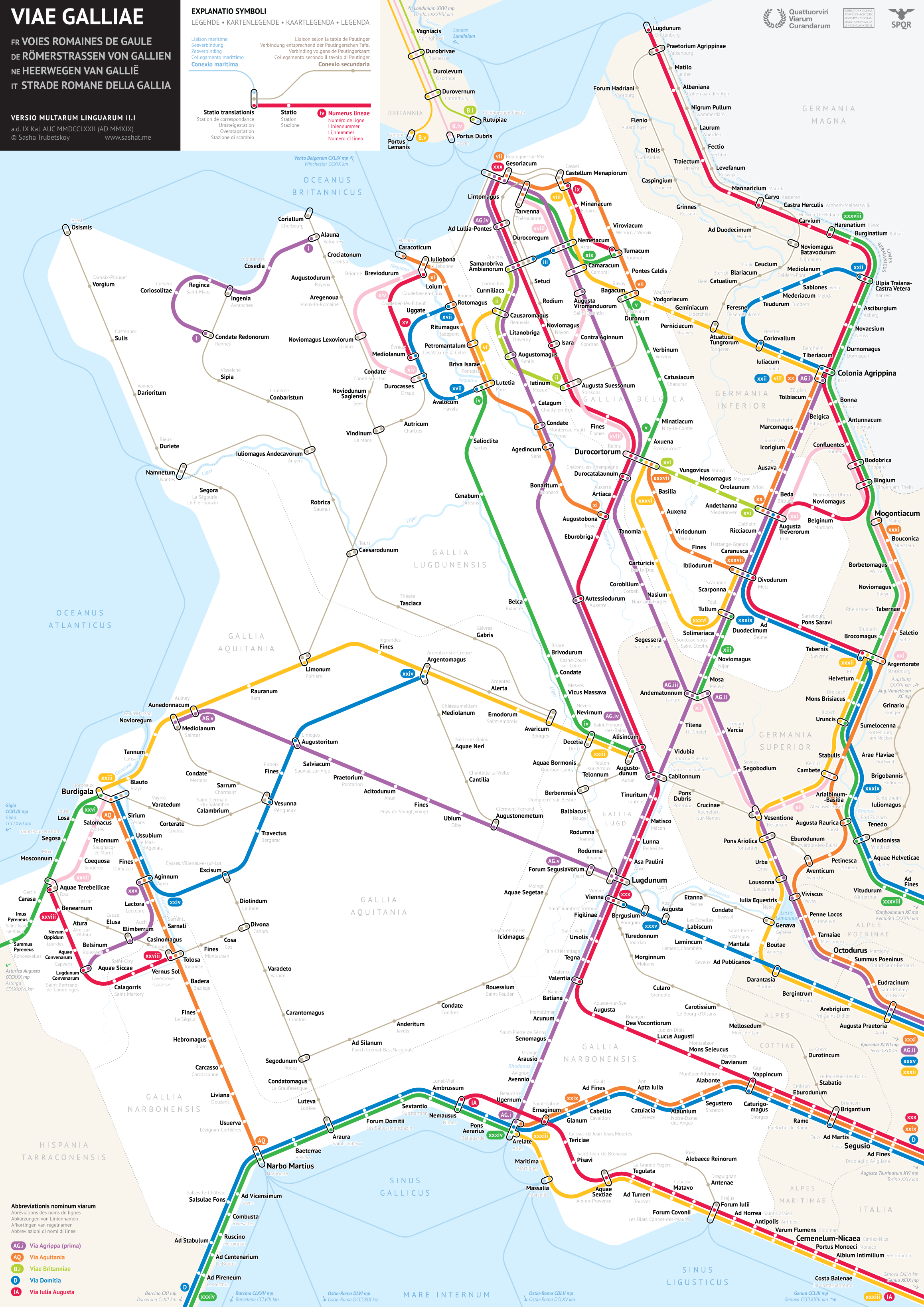

At a casual glance, some travelers may take the map above for a depiction of France’s enviable intercity high-speed rail network Train à Grande Vitesse, better known as TGV. In reality, its content predates that system’s inauguration in the early 1980s — and by nearly two millennia at that. This is in fact a map of Gaul, a region of Europe that, most broadly defined, included modern-day France, Luxembourg, and Belgium, as well as parts of Switzerland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany. Ruled by Rome for five centuries until the fall of the Roman Empire itself, Gaul was run through with a number of Roman roads, a subject of fascination for many archaeologically inclined historians.

They’ve also become a subject of fascination for a young data scientist and graphic designer by the name of Sasha Trubetskoy. His work, much featured here on Open Culture, includes maps of the Roman Roads of Britain, Italy, Spain and Portugal, as well as, at a larger scale, those of the entire empire.

“This was an interesting map to make, but I can’t say it was fun all the time,” writes Trubetskoy. “Generally I enjoyed the process, but it was far more challenging than I had anticipated.” You can hear him describe some of the challenges involved, and even show how solving them played out in his design process, in his three-hour explanatory live stream now archived on Youtube.

You can download Trubetskoy’s Roman Roads of Gaul map from his site, and even buy a high-resolution file suitable for printing as a poster (USD $9). “As far as I can tell, it’s done,” writes Trubetskoy of the work, wisely — or from frustrating personal experience — acknowledging that, despite or because of the centuries of distance between us and the relevant historical and geographical facts, those facts could still change. Just as ancient history cannot both make its way to us and maintain absolutely perfect fidelity to the past, so the kind of practical visual design embodied in a subway map necessitates a great deal of simplification and approximation to be useful. And speaking of the graphic arts, just imagine how useful this particular map would’ve been to Asterix.

Related Content:

Ancient Rome’s System of Roads Visualized in the Style of Modern Subway Maps

The Roman Roads of Britain Visualized as a Subway Map

All the Roman Roads of Italy, Visualized as a Modern Subway Map

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.