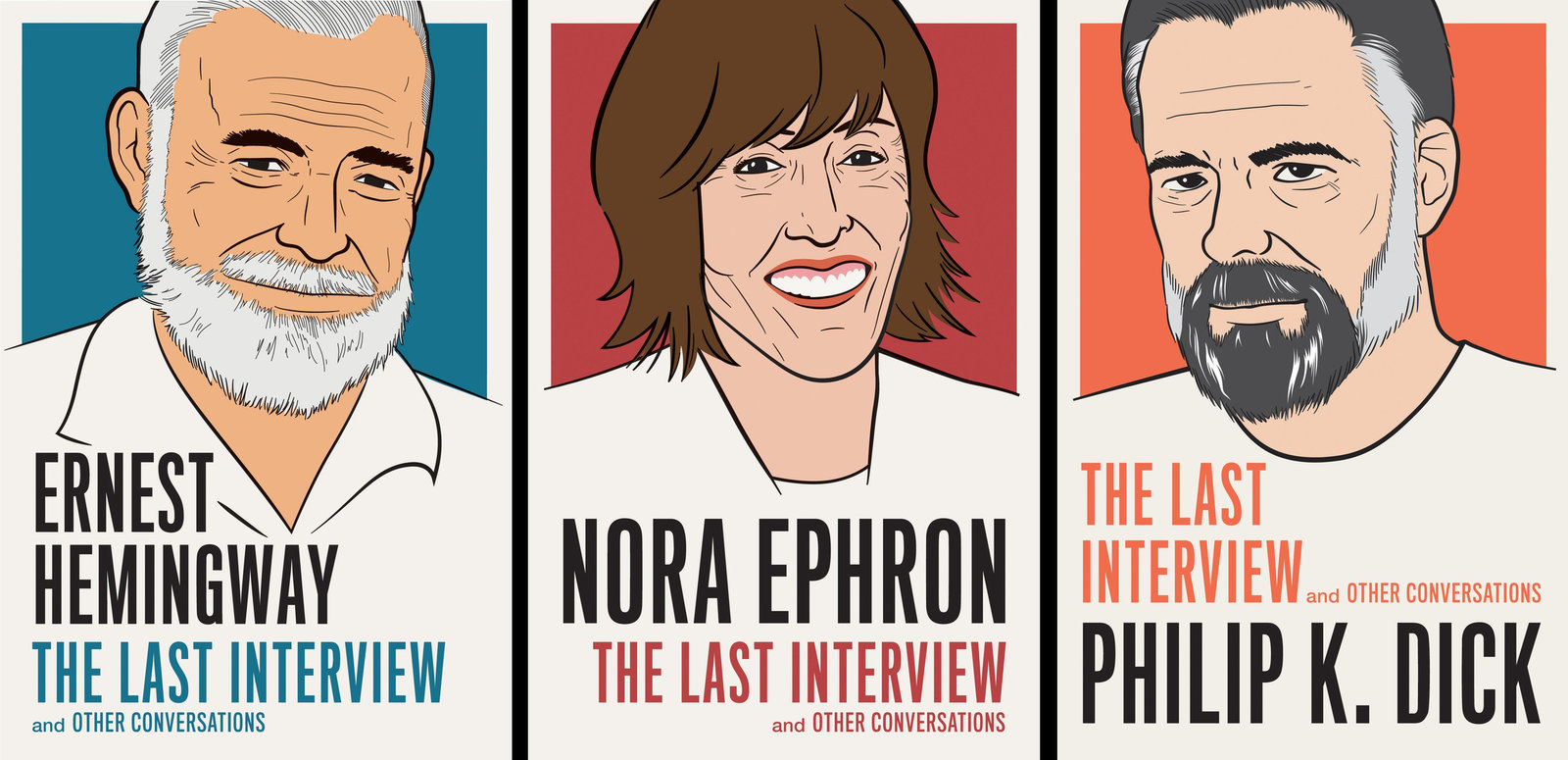

Dick Cavett was sometimes called the “thinking man’s Johnny Carson,” and he came up in a similar fashion—a stand-up, a joke writer for hire— until he was given a chance to host a late night show. But compare a Cavett episode to any late night host today, and it feels like a very different time. Sure, stars were booked to talk about their upcoming movie or album or television show, but Cavett was so laid back, so chatty and conversant, that it often felt like you were eavesdropping. It’s a style you find more on podcasts these days than television—Cavett is genuinely inquisitive. He never got high ratings because of it, but he certainly got an impressive guest list.

We’ve been writing about some of the clips here on Open Culture, but Shout! Factory, the DVD company that has pivoted to streaming, offers full episodes of Dick Cavett’s show to watch for free. They sometimes have ads, but these days so do most YouTube channels we feature. (Of the episodes I let run, I didn’t really see any commercials so your mileage may vary as they say).

And what a cultural trove is there on their site: a selected history of Cavett’s show, arranged into themed “seasons” that stretch from 1969 to 1995. There’s “Rock Icons” (Sly Stone, Janis Joplin, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, George Harrison, David Bowie, Frank Zappa, etc.),

“Hollywood Greats” (Alfred Hitchcock, Groucho Marx, Betty Davis, et al), authors, sports icons, politicians, visionaries (from Jim Henson to Terry Gilliam), film directors (including Akira Kurosawa, Jean-Luc Godard, and Ingmar Bergman), and one called “Black History Month” although it’s from different months and different years, featuring interviews with Shirley Chisholm, Alice Walker, and James Earl Jones. (Let’s also mention that Cavett’s interview with John Cassavetes, Peter Falk, and Ben Gazzara is one of the most anarchic television interviews in history). Enter the Cavett collection here.

Along similar lines, Shout! Factory features 18 themed “seasons” of The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, the man who refined the talk show template that late night has followed ever since. There’s “Animal Antics” with Carson encountering various zoo animals brought on by Joan Embery and Jim Fowler; a wide selection of stand-up comedians—The Tonight Show was considered the big break for any comedian (and sometimes future host); and a selection of Hollywood legends. (View the episodes here.)

In fact, the whole website is a fantastic time-suck of the first order: a huge assortment of Mystery Science Theater 3000, episodes of Ernie Kovacs, The Prisoner and its prequel of sorts Secret Agent, and much more.

And a special mention to hosting the first season of Soul! the 1968–69 performance/variety hour that exclusively focused on the African-American experience. In its heyday, Soul! was watched by nearly three-quarters of the Black population. And why not: guests included Muhammad Ali, James Baldwin, Bill Withers, Al Green, Gladys Knight, Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, and jazz legends Lee Morgan, Horace Silver, and Bobbi Humphrey.

Explore the entire Shout! Factory media collection.

Related Posts:

Carl Sagan Issues a Chilling Warning to America in His Final Interview (1996)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.