The modern artist has what can seem like an unlimited range of materials from which to choose, a variety completely unknown to great Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci. Few, if any, can say, however, that they have anything like the raw talent, ingenuity, and discipline that drove Leonardo to draw incessantly, constantly honing his techniques and exploiting every use of the tools and techniques available to him.

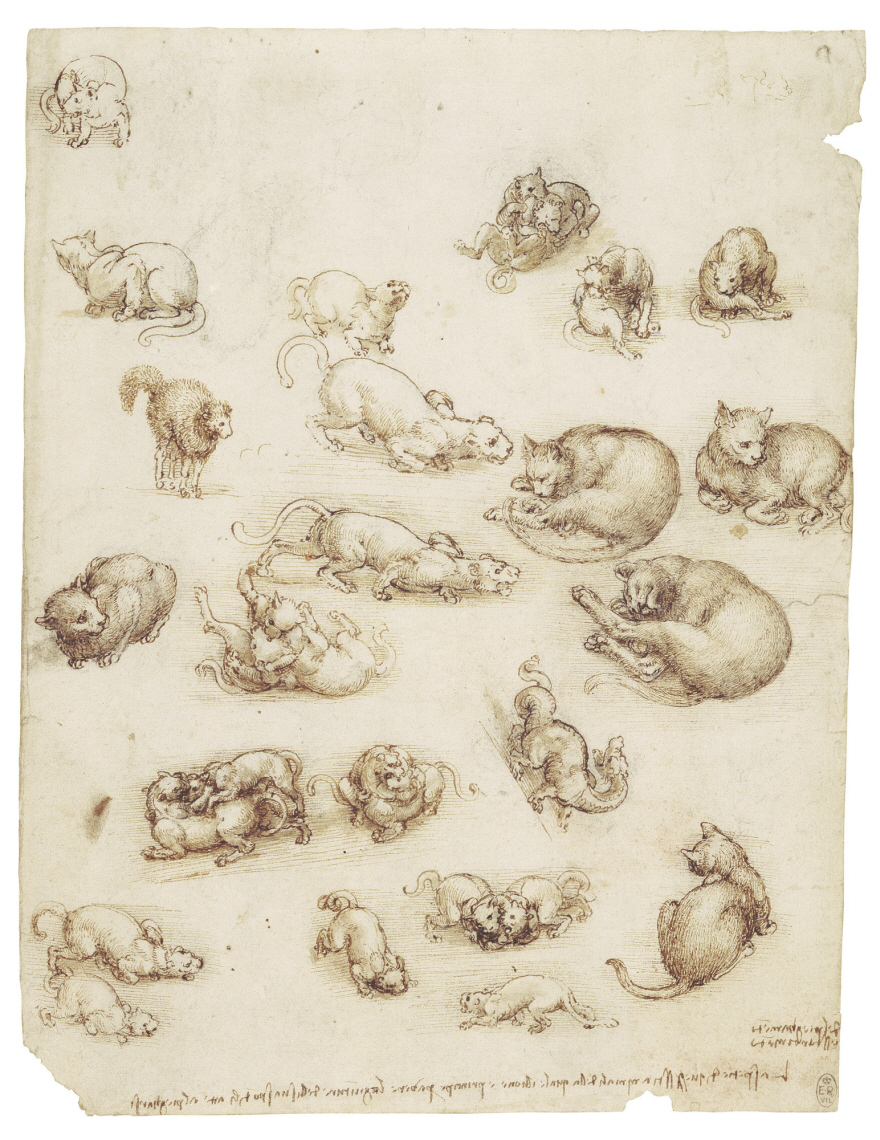

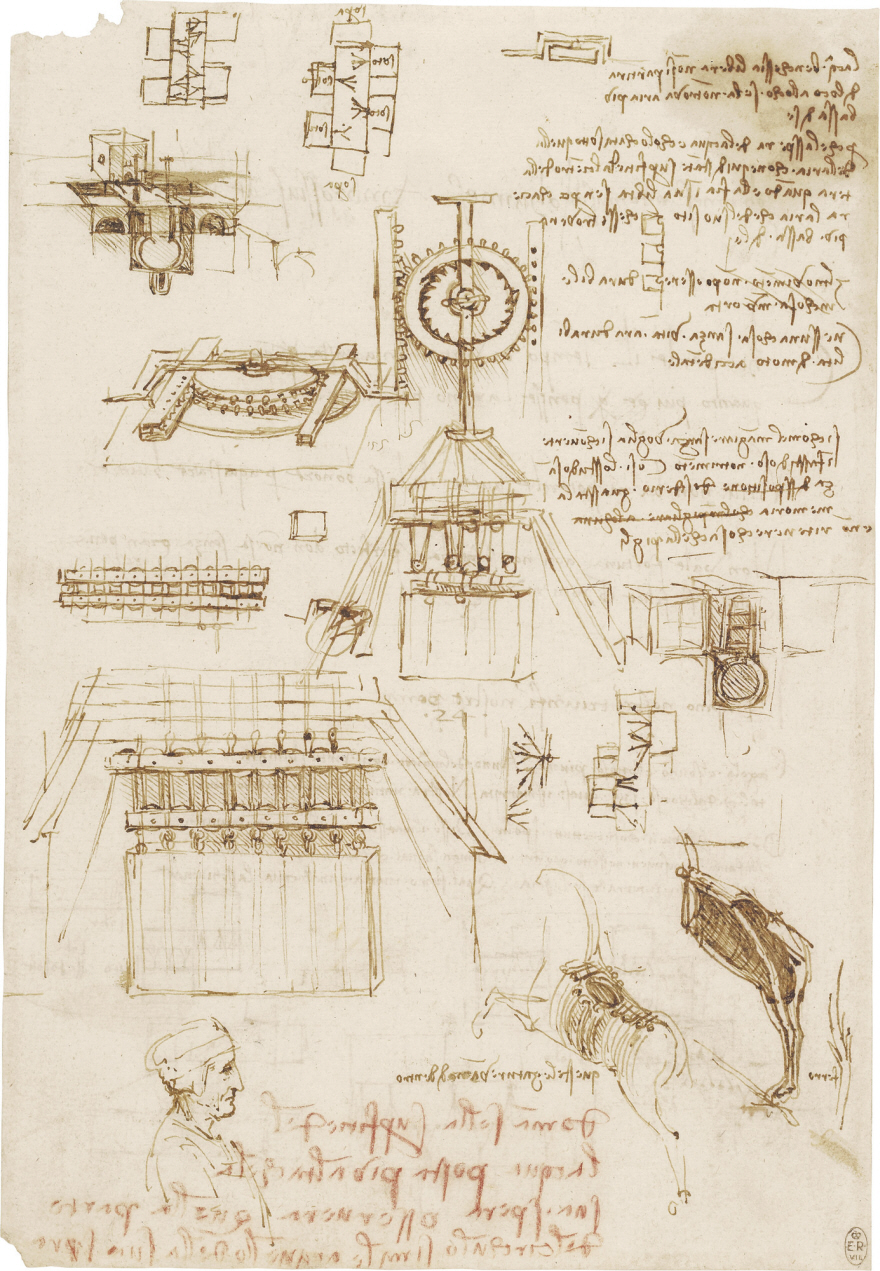

What were those tools and techniques? Conservator Alan Donnithorne demonstrates Leonardo’s materials in the video above, with examples from the holdings of the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. Leonardo “drew incessantly,” the Royal Collection Trust writes, “to devise his artistic projects, to explore the natural world, and to record the workings of his imagination.” He used metalpoint, a method of drawing on coated paper with a metal stylus; pen and ink, with pens made from a goose wing feather; and, after the 1490s, red and black chalks.

Leonardo produced thousands of drawings during his lifetime“many of them of extreme beauty and complexity,” says Donnithorne, “and it’s incredible to think that he produced them using these very simple ingredients.”

The Royal Collection owns around 550 of these drawings, “together as a group since the artist’s death in 1519,” when he bequeathed them to his student, Francesco Melzi. These works “provide unparalleled insight,” the Collection writes, “into the workings of Leonardo’s mind and reflect the full range of his interests, including painting, sculpture, architecture, anatomy, engineering, cartography, geology, and botany.”

The restlessness of Leonardo’s mind and hand also reflect the need to move quickly from project to project as he pursued some commissions and abandoned others. “Across all these themes,” however, Christopher Baker, director of European and Scottish Art and Portraiture at the National Galleries of Scotland, sees “a ravishing range of techniques and materials…. The precision required by metalpoint proved especially appropriate for some of his most incisive human or animal observations, while iron gall ink and red and black chalks allowed an exploratory freedom fitting for compositional trials, fictive works or capturing movement.”

The artist’s “prodigious skills” are evident among his many shifts in style and subject and we see even in utilitarian illustrations how “he overturned so many conventions and sometimes mixed his media to wonderful effect.” Leonardo’s choice of media was hardly expansive compared to the dizzyingly colorful aisles that greet the budding artist at art supply stores today. But what he could do with a stylus, goose-quill pen, and chalk has never been equalled. Learn more about how he used his materials in Donnithorne’s book, Leonardo da Vinci: A Closer Look, published on the 500th anniversary celebrations of Leonardo’s death.

via Core77

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Studies of the Human Heart Were 500 Years Ahead of Their Time

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness