In the perennial conflict between art and our corporate entertainment machine, animation seems designed to be mechanized, given how labor-intensive it is, and yes, most of our animation comes aimed at children (or naughty adults) from a few behemoths (like, say, Disney).

Your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by Benjamin Goldman to discuss doing animation on your own, with only faint hope of “the cavalry” (e.g. Netfilx money or the Pixar fleet of animators) coming to help you realize (and distribute and generate revenue from) your vision. As an adult viewer, what are we looking for from this medium?

We talk about what exactly constitutes “indie,” shorts vs. features, how the image relates to the narration, realism or its avoidance, and more. Watch Benjamin’s film with Daniel Gamburg, “Eight Nights.”

Some of our other examples include Jérémy Clapin’s I Lost My Body and Skhizein, World of Tomorrow, If Anything Happens I Love You, The Opposites Game, Windup, Fritz the Cat, Spike & Mike’s Sick and Twisted Festival of Animation, and Image Union.

Hear a few lists and comments about this independent animation:

- Some history from Wikipedia

- “How Independent European Animation Is Taking on the US Studios” by Geoffrey Macnab

- “The 20 Best Indie Animation Features of the 2010s” by Vassilis Kroustallis

- “Oscars Predictions: Best Animated Short – Netflix’s Look at the Aftermath of School Shootings is the One to Beat” by Clayton Davis

- “Oscars Predictions: Best Animated Feature – Can Anything Beat ‘Soul’ at the Oscars?” by Clayton Davis

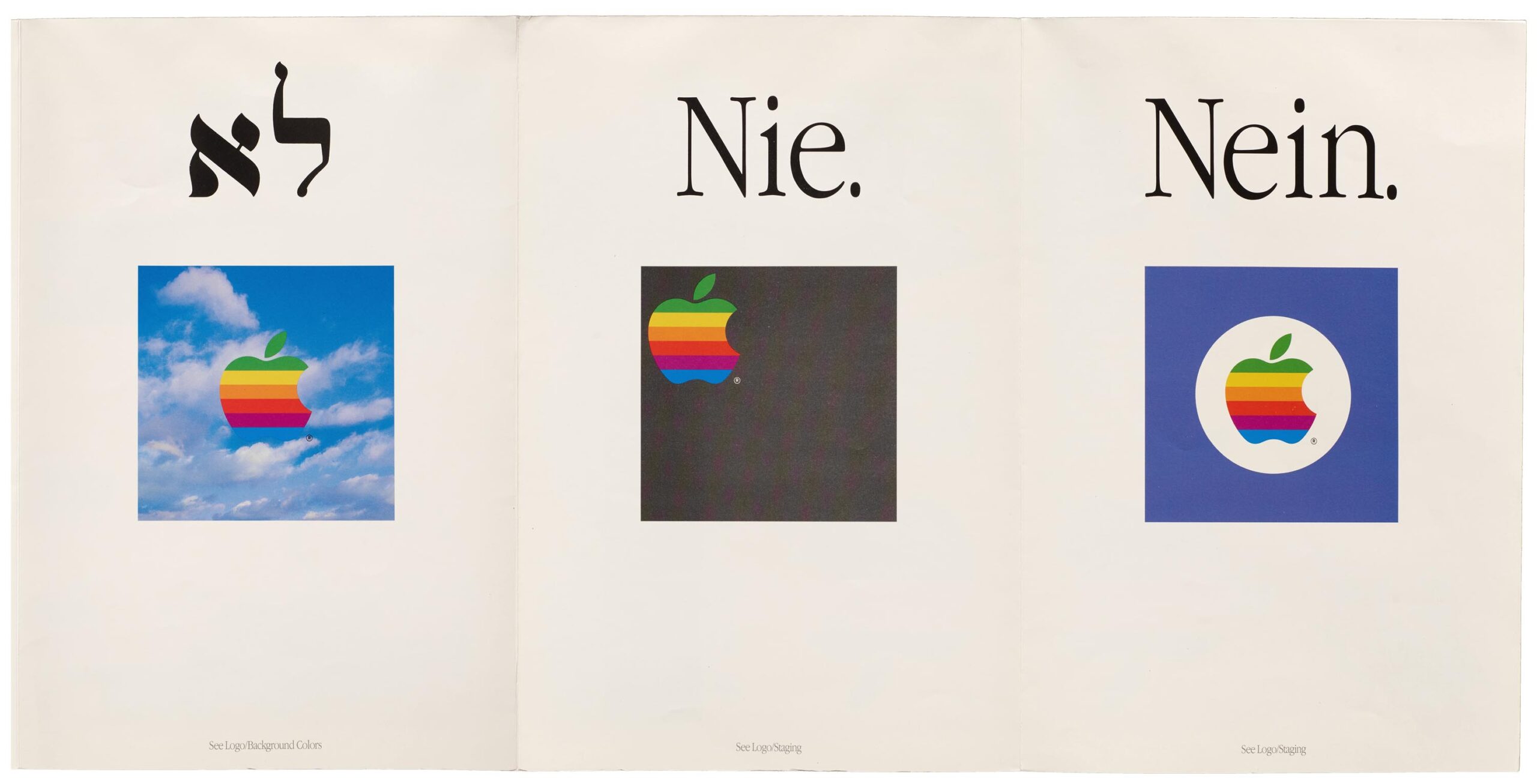

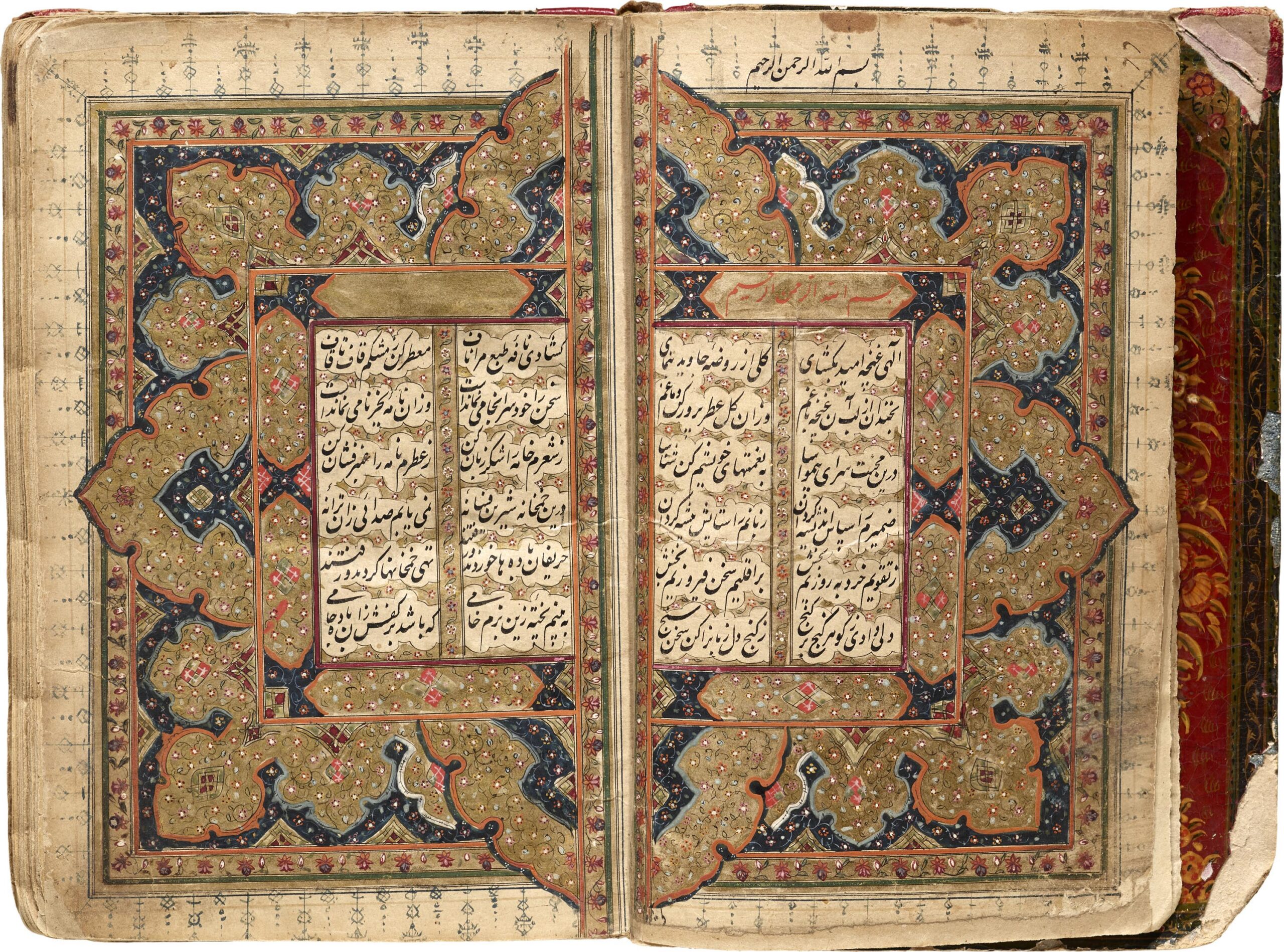

Follow Benjamin on Instagram @bgpictures. Here’s something he did for a major film studio that you might recognize, from the film version of A Series of Unfortunate Events:

Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.