Georges Méliès directed, produced, edited, and starred in over 500 films between 1896 and 1913, most of them brimming with special effects the filmmaker himself invented. Before Méliès, such things as split screens, dissolves, and double exposures did not exist. After him, they were critical to cinema’s vocabulary, and the image of a rocket in the Moon’s eye became iconic. Méliès shocked, scared, and delighted popular audiences while also earning recognition from the avant garde. “The Surrealists would hail him as a great poet,” writes Darrah O’Donohue at Senses of Cinema, “in particular his erasure or subversion of boundaries.” Critics would later call him the first auteur.

Méliès originally set out to become a stage illusionist. He performed in — and purchased, in 1888 — famous magician Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin’s theater, where he became obsessed with film in 1895 at a private demonstration of the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph. When they refused to sell him one, he hunted down another projector — Robert W. Paul’s animatograph — and modified it to work as a camera he called the “coffee grinder” and “machine gun.”

Noisy cameras were not a serious issue in the age of silent film, but Méliès was perpetually dissatisfied with his equipment and strove to improve at every turn while learning to make better cinematic illusions, 194 of which you can watch for free in chronological order in this YouTube playlist. The playlist appears in full at the bottom of this post.

In an autobiographical sketch (ghostwritten in the third person for a journalist tasked with compiling a “dictionary of illustrious men”), Méliès describes himself “an engineer of great precision” and “ingenious by nature.” Modest, he was not, but the great showman was not wrong about his critical importance to early film. He describes the difficulties in detail, prefacing them with a statement about the mechanical heroism of the first filmmakers.

Those who today seek to make motion pictures will find all the required equipment available, complete and perfected: all they need is the necessary funds. They cannot begin to imagine the difficulties against which the creators of this industry had to struggle, at a time when no such material yet existed and when each innovator kept their work and research a closely guarded secret. Therefore Méliès, just like Pathé, Gaumont and others, was only able to progress by making numerous machines, subsequently abandoned and replaced by others which were themselves in due course replaced.

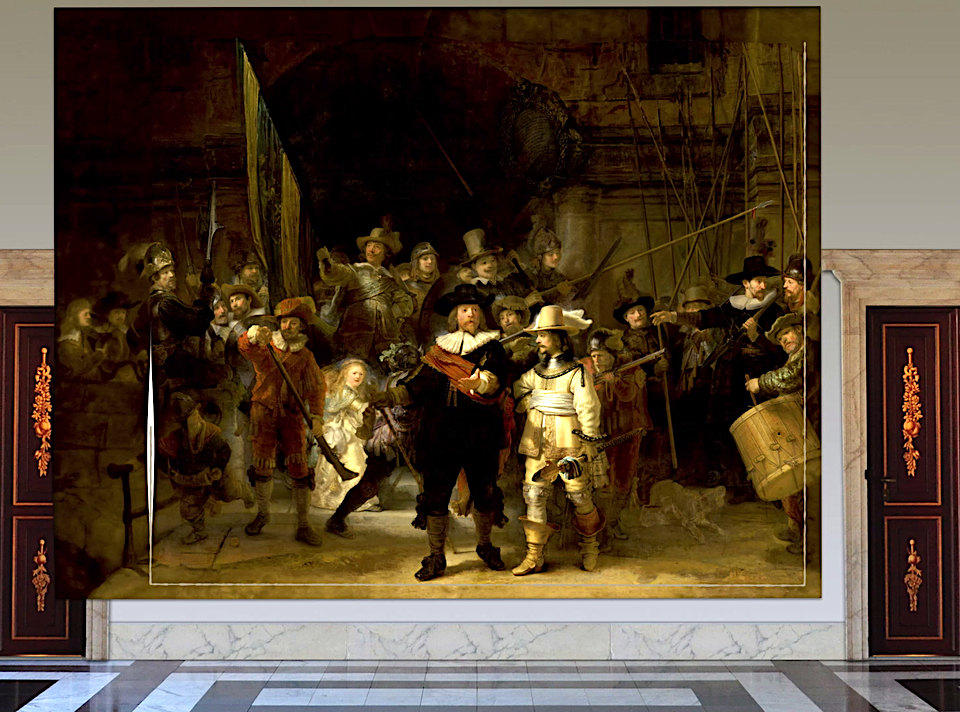

Celebrated as the ultimate fantasist in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, Méliès now presides over one of cinema’s great ironies. As he helped invent cinema, he also invented the special effects-laden genre film — the sort of thing Scorsese has denied the status of cinematic art. Méliès directed the first horror film, The Haunted Castle (above) and first adaptation of Cinderella (top). He built the first film studio in Europe while making and starring in hundreds of fantasies, ranging from one minute to 40 minutes. While computers do most of the labor in the kinds of genre films we’re used to seeing now, it’s safe to say, for better or worse, that without Méliès, there would be no Marvel Universe.

But without Méliès, there would also be no Scorsese, as he says himself: “Méliès,” argues the director of such gritty neo-realist films as Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, “invented everything.” His technological innovations are only a small part of his influence. “The locked room, containing forbidden sights, darkened but illumined,” O’Donohue observes, “becomes the metaphor for Méliès’ cinema, a manifestation of private desires in a public or communal medium. The flat theatricality of the social world gives way to ‘effects,’ vision, dreams, nightmares, desires, fears, perversions — the releasing of the unconscious and the inner life.” Find films by Méliès in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

A Trip to the Moon (and Five Other Free Films) by Georges Méliès, the Father of Special Effects

The First Horror Film, George Méliès’ The Haunted Castle (1896)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness