The Stettheimer Dollhouse has been wowing young New Yorkers since it entered the Museum of the City of New York’s collection in 1944.

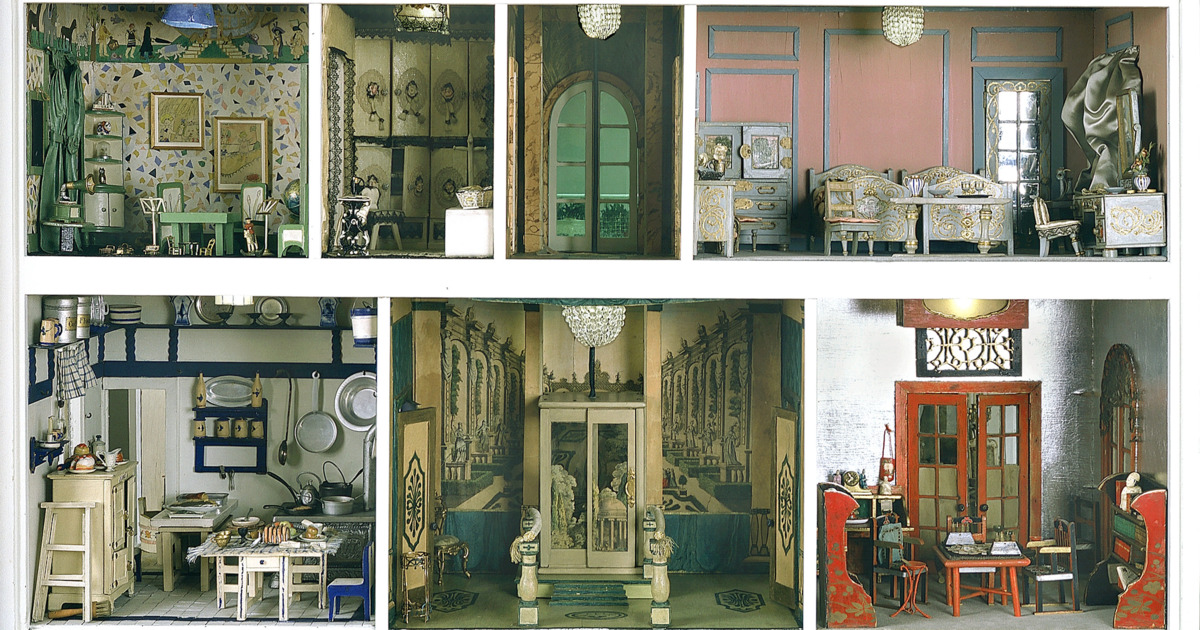

The luxuriously appointed, two-story, twelve-room house features tiny crystal chandeliers, trompe l’oeil panels, an itty bitty mah-jongg set, and a delicious-looking dessert assortment that would have driven Beatrix Potter’s Two Bad Mice wild.

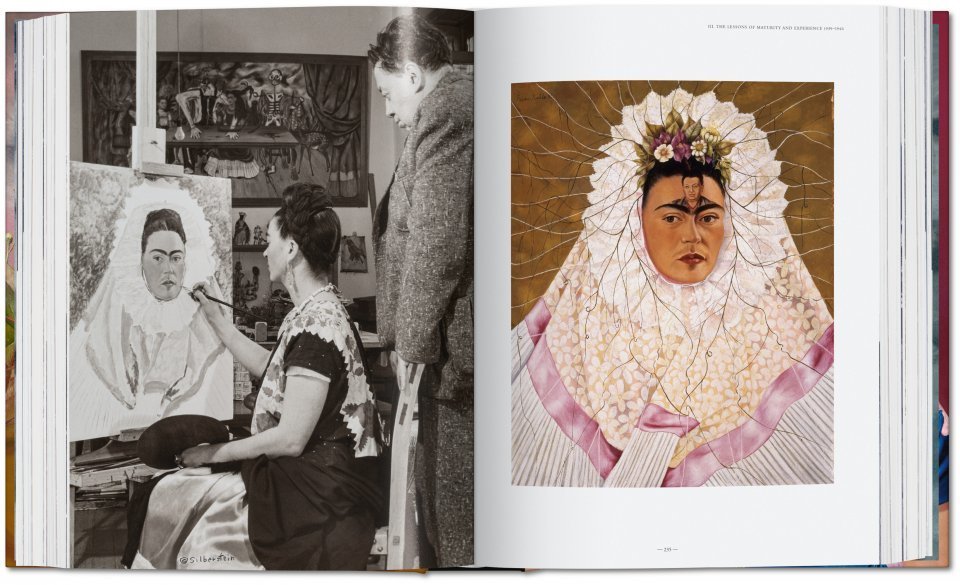

Its most astonishing feature, however, tends to go over its youngest fans’ heads — an art gallery filled with original modernist paintings, drawings, and sculptures by the likes of Marcel Duchamp, George Bellows, Gaston Lachaise, and Marguerite Zorach.

The house’s creator, Carrie Walter Stettheimer, drew on her family’s close personal ties to the avant-garde art world to secure these contributions.

The art dealer Paul Rosenberg described the affinity between these artists and the three wealthy Stettheimer sisters, one of whom, Florine, was herself a modernist painter:

Artists… went there and not at all merely because of the individualities of the trio of women and their tasteful hospitality. They went for the reason that they felt themselves entirely at home with the Stetties—so the trio was called—and the Stetties seemed to feel themselves entirely at home in their company. Art was an indispensable component of the modern, open intellectual life of the place. The sisters felt it as a living issue. Sincerely they lived it.

Art is definitely part of the dollhouse’s life.

Duchamp recreated Nude Descending a Staircase, inscribing the back “Pour la collection de la poupée de Carrie Stettheimer à l’occasion de sa fête en bon souvenir. Marcel Duchamp 23 juillet 1918 N.Y.”

Marguerite Thompson Zorach, Alexander Archipenko, and Paul Thevenaz also felt no compunction about furnishing a dollhouse with nudes.

Louis Bouché — the “bad boy of American art” as per the Stettheimers’ friend, writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten, made a tiny version of his painting, Mama’s Boy.

Carrie wrote to Gaston Lachaise, to thank him for two miniature nude drawings and an alabaster Venus:

My dolls and I thank you most sincerely for the lovely drawings that are to grace their art gallery. I think that the dolls—after they are born, which they are not, yet—ought to be the happiest and proudest dolls in the world as owners of the drawings and the beautiful statue. I am now hoping that they will never be born, so that I can keep them [the art works] forever in custody, and enjoy them myself, while awaiting their arrival.

Carrie worked on the dollhouse from from 1916 to 1935. Her sister Ettie donated it to the museum and took it upon herself to arrange the artwork. As Johanna Fateman writes in 4Columns:

Twenty-eight of the artists’ gifts were stored separately; Ettie selected thirteen from the collection, and her graceful arrangement became permanent, though it’s likely that the pieces were meant to be shown in rotation.

The Museum of the City of New York’s current exhibition, The Stettheimer Dollhouse: Up Close, includes photos of the artworks that Ettie did not choose to install.

The works that have always been on view are Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, Alexander Archipenko’s Nude, Louis Bouche’s Mama’s Boy, Gaston Lachaise’s Venus and two nudes, Carl Sprinchorn’s Dancers, Albert Gleizes’ Seated Figure and Bermuda Landscape, Paul Thevenaz’s L’Ombre and Nude with Flowing Hair, Marguerite Zorach’s Bather and Bathers, William Zorach’s Mother and Child, and a painting of a ship by an unknown artist.

Related Content:

The Gruesome Dollhouse Death Scenes That Reinvented Murder Investigations

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.