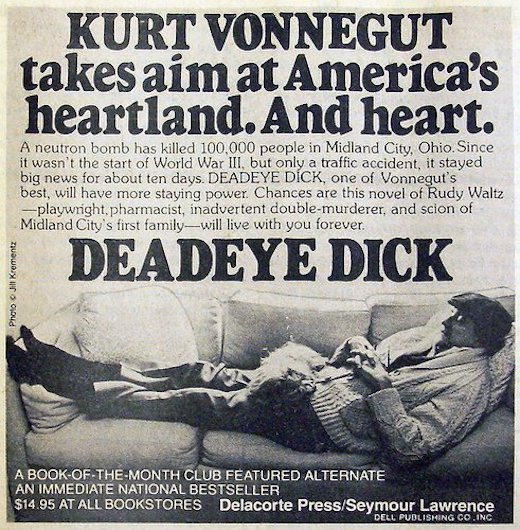

Author Kurt Vonnegut incorporated several recipes into his 1982 novel Deadeye Dick, inspired by James Beard’s American Cookery, Marcella Hazan’s The Classic Italian Cook Book, and Bea Sandler’s The African Cookbook.

He writes in the preface that these recipes are intended to provide “musical interludes for the salivary glands,” warning readers that “no one should use this novel for a cookbook. Any serious cook should have the reliable originals in his or her library anyway.”

So with that caveat in mind…

Early on, the narrator/titular character, née Rudy Waltz, shares a recipe from his family’s former cook, Mary Hoobler, who taught him “everything she knew about cooking and baking”:

MARY HOOBLER’S CORN BREAD

Mix together in a bowl half a cup of flour, one and a half cups of yellow corn-meal, a teaspoon of salt, a teaspoon of sugar, and three teaspoons of baking powder.

Add three beaten eggs, a cup of milk, a half cup of cream, and a half cup of melted butter.

Pour it into a well-buttered pan and bake it at four hundred degrees for fifteen minutes.

Cut it into squares while it is still hot. Bring the squares to the table while they are still hot, and folded in a napkin.

Barely two paragraphs later, he’s sharing her barbecue sauce. It sounds delicious, easy to prepare, and its placement gives it a strong flavor of Slaughterhouse-Five’s “so it goes” and “Poo-tee-weet?” — as ironic punctuation to Father Waltz’s full on embrace of Hitler, a seeming non sequitur that forces readers to think about what comes before:

When we all posed in the street for our picture in the paper, Father was forty-two. According to Mother, he had undergone a profound spiritual change in Germany. He had a new sense of purpose in life. It was no longer enough to be an artist. He would become a teacher and political activist. He would become a spokesman in America for the new social order which was being born in Germany, but which in time would be the salvation of the world.

This was quite a mistake.

MARY HOOBLER’S BARBECUE SAUCE

Sauté a cup of chopped onions and three chopped garlic cloves in a quarter of a pound of butter until tender.

Add a half cup of catsup, a quarter cup of brown sugar, a teaspoon of salt, two teaspoons of freshly ground pepper, a dash of Tabasco, a tablespoon of lemon juice, a teaspoon of basil, and a tablespoon of chili powder.

Bring to a boil and simmer for five minutes.

Rudy’s father is not the only character to falter.

Rudy’s mistake happens in the blink of an eye, and manages to upend a number of lives in Midland City, a stand in for Indianapolis, Vonnegut’s hometown.

His family loses their money in an ensuing lawsuit, and can no longer engage Mary Hoobler and the rest of the staff.

Young Rudy, who’s spent his childhood hanging out with the servants in Mary’s cozy kitchen, finds it “easy and natural” to cater to his parents in the manner to which they were accustomed:

As long as they lived, they never had to prepare a meal or wash a dish or make a bed or do the laundry or dust or vacuum or sweep, or shop for food. I did all that, and maintained a B average in school, as well.

What a good boy was I!

EGGS À LA RUDY WALTZ (age thirteen)

Chop, cook, and drain two cups of spinach.

Blend with two tablespoons of butter, a teaspoon of salt, and a pinch of nutmeg.

Heat and put into three oven-proof bowls or cups.

Put a poached egg on top of each one, and sprinkle with grated cheese.

Bake for five minutes at 375 degrees. Serves three: the papa bear, the mama bear, and the baby bear who cooked it—and who will clean up afterwards.

By high school, Rudy’s heavy domestic burden has him falling asleep in class and reproducing complicated desserts from recipes in the local paper. (“Father roused himself from living death sufficiently to say that the dessert took him back forty years.”)

LINZER TORTE (from the Bugle-Observer)

Mix half a cup of sugar with a cup of butter until fluffy.

Beat in two egg yolks and half a teaspoon of grated lemon rind.

Sift a cup of flour together with a quarter teaspoon of salt, a teaspoon of cinnamon, and a quarter teaspoon of cloves. Add this to the sugar-and-butter mixture.

Add one cup of unblanched almonds and one cup of toasted filberts, both chopped fine.

Roll out two-thirds of the dough until a quarter of an inch thick.

Line the bottom and sides of an eight-inch pan with dough.

Slather in a cup and a half of raspberry jam.

Roll out the rest of the dough, make it into eight thin pencil shapes about ten inches long. Twist them a little, and lay them across the top in a decorative manner. Crimp the edges.

Bake in a preheated 350-degree oven for about an hour, and then cool at room temperature.

A great favorite in Vienna, Austria, before the First World War!

Rudy eventually relocates to the Grand Hotel Oloffson in Port au Prince, Haiti, which is how he manages to survive the — SPOILER — neutron bomb that destroys Midland City.

Here is a recipe for chocolate seafoams, courtesy of one of Midland City’s fictional residents:

MRS. GINO MARTIMO’S SPUMA DI CIOCCOLATA

Break up six ounces of semisweet chocolate in a saucepan.

Melt it in a 250-degree oven.

Add two teaspoons of sugar to four egg yolks, and beat the mixture until it is pale yellow.

Then mix in the melted chocolate, a quarter cup of strong coffee, and two tablespoons of rum.

Whip two-thirds of a cup of cold, heavy whipping cream until it is stiff. Fold it into the mixture.

Whip four egg whites until they form stiff peaks, then fold them into the mixture.

Stir the mixture ever so gently, then spoon it into cups, each cup a serving.

Refrigerate for twelve hours.

Serves six.

Other recipes in Rudy’s repertoire originate with the Grand Hotel Oloffson’s most valuable employee, headwaiter and Vodou practitioner Hippolyte Paul De Mille, who “claims to be eighty and have fifty-nine descendants”:

He said that if there was any ghost we thought should haunt Midland City for the next few hundred years, he would raise it from its grave and turn it loose, to wander where it would.

We tried very hard not to believe that he could do that.

But he could, he could.

HAITIAN FRESH FISH IN COCONUT CREAM

Put two cups of grated coconut in cheesecloth over a bowl.

Pour a cup of hot milk over it, and squeeze it dry.

Repeat this with two more cups of hot milk. The stuff in the bowl is the sauce.

Mix a pound of sliced onions, a teaspoon of salt, a half teaspoon of black pepper, and a teaspoon of crushed pepper.

Sauté the mixture in butter until soft but not brown.

Add four pounds of fresh fish chunks, and cook them for about a minute on each side.

Pour the sauce over the fish, cover the pan, and simmer for ten minutes. Uncover the pan and baste the fish until it is done—and the sauce has become creamy.

Serves eight vaguely disgruntled guests at the Grand Hotel Oloffson.

HAITIAN BANANA SOUP

Stew two pounds of goat or chicken with a half cup of chopped onions, a teaspoon of salt, half a teaspoon of black pepper, and a pinch of crushed red pepper. Use two quarts of water.

Stew for an hour.

Add three peeled yams and three peeled bananas, cut into chunks.

Simmer until the meat is tender. Take out the meat. What is left is eight servings of Haitian banana soup.

Bon appétit!

The recipe that closes the novel is couched in an anecdote that’s equal parts scatology and epiphany.

As a daughter of Indianapolis who was a junior in high school the year Deadeye Dick was published, I can attest that Polka-Dot Brownies would have been a hit at the bake sales of my youth:

POLKA-DOT BROWNIES

Melt half a cup of butter and a pound of light-brown sugar in a two-quart saucepan. Stir over a low fire until just bubbly.

Cool to room temperature.

Beat in two eggs and a teaspoon of vanilla.

Stir in a cup of sifted flour, a half teaspoon of salt, a cup of chopped filberts, and a cup of semisweet chocolate in small chunks.

Spread into a well-greased nine-by-eleven baking pan.

Bake at two hundred and thirty-five degrees for about thirty-five minutes.

Cool to room temperature, and cut into squares with a well-greased knife.

Enjoy, in moderation of course.

I was wearing my best suit, which was as tight as the skin of a knackwurst. I had put on a lot of weight recently. It was the fault of my own good cooking. I had been trying out a lot of new recipes, with considerable success. — Rudy Waltz

Related Content:

Why Should We Read Kurt Vonnegut? An Animated Video Makes the Case

Watch a Sweet Film Adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s Story, “Long Walk to Forever”

The Recipes of Iconic Authors: Jane Austen, Sylvia Plath, Roald Dahl, the Marquis de Sade & More

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday