The internet as we know it today began with a coffee pot. Despite the ring of exaggeration, that claim isn’t actually so far-fetched. When most of us go online, we expect something new: often not just something new to read, but something new to watch. This, as those of us past a certain age will recall, was not the case with the early World Wide Web, consisting as it mostly did of static pages of text, updated irregularly if at all. Younger readers will have to imagine even that being a cutting-edge thrill, but we didn’t really feel like we were living in the future until the fall of 1993, when XCoffee first went live.

This groundbreaking technological project “started back in the dark days of 1991,” writes co-creator Quentin Stafford-Fraser, “when the World Wide Web was little more than a glint in CERN’s eye.” At the time, Stafford-Fraser was employed as one of fifteen researchers in the “Trojan Room” of the University of Cambridge Computer Lab. “Being poor, impoverished academics, we only had one coffee filter machine between us, which lived in the corridor just outside the Trojan Room. However, being highly dedicated and hard-working academics, we got through a lot of coffee, and when a fresh pot was brewed, it often didn’t last long.”

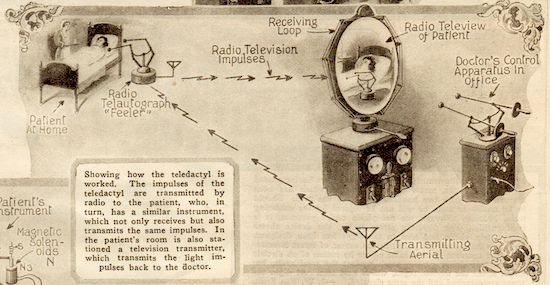

It occurred to Stafford-Fraser to train an unused video camera from the Trojan Room on the coffee pot (and thus the amount of coffee available within), then connect it to a computer, specifically an Acorn Archimedes. His colleague Paul Jardetzky “wrote a ‘server’ program, which ran on that machine and captured images of the pot every few seconds at various resolutions, and I wrote a ‘client’ program which everybody could run, which connected to the server and displayed an icon-sized image of the pot in the corner of the screen. The image was only updated about three times a minute, but that was fine because the pot filled rather slowly, and it was only greyscale, which was also fine, because so was the coffee.”

XCoffee, the resulting program, was meant only to provide this much-needed information to Computer Lab members elsewhere in the building. But after the release of image-displaying web browsers in 1993, it found a much wider audience as the world’s first streaming webcam. Stafford-Fraser’s successors “resurrected the system, treated it to a new frame grabber, and made the images available on the World Wide Web. Since then, hundreds of thousands of people have looked at the coffee pot, making it undoubtedly the most famous in the world.” Stafford-Fraser wrote these words in 1995; in the years thereafter XCoffee went on to receive millions of views before its eventual shutdown in 2001.

In the Centre for Computing History video above, Stafford-Fraser shows the very Olivetti camera he originally used to monitor the coffee level. (He’d previously worked at the Olivetti Research Laboratory, whose parent company also owned Acorn Computers.) “We could see things at a distance before,” he says. “We could view television programs, we could look through telescopes.” But only after the Trojan Room’s coffee pot hit the internet could we “see what’s happening now, somewhere else in the world,” on demand. Thirty years after XCoffee’s development, we’re mesmerized by live-streaming stars and surrounded by “smart” home appliances, hoping for nothing so much as way to concentrate on our immediate surroundings again — to wake up, if you like, and smell the coffee.

Related Content:

See Web Cams of Surreally Empty City Streets in Venice, New York, London & Beyond

The Coffee Pot That Fueled Honoré de Balzac’s Coffee Addiction

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.