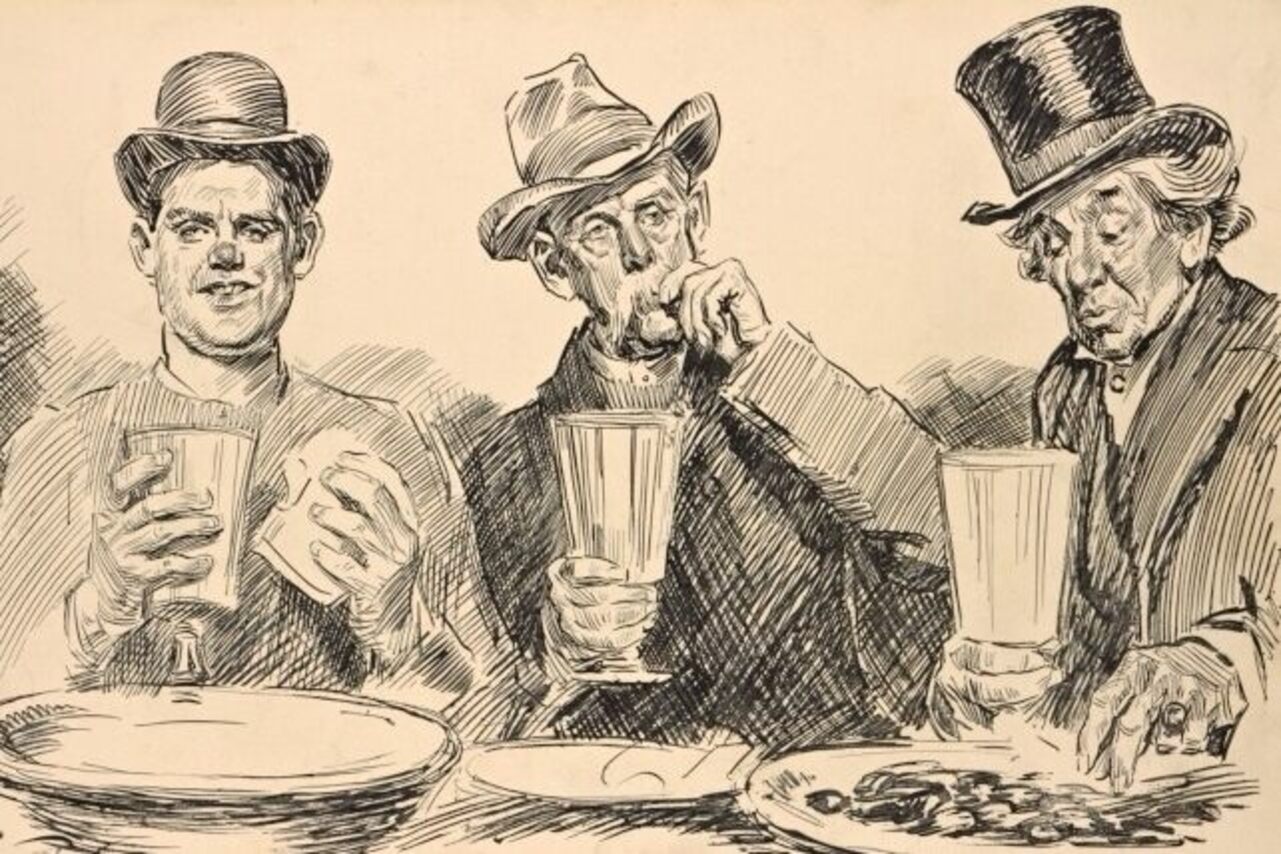

Three men feast on free lunch in a drawing by Charles Dana Gibson

In one of my favorite episodes of The Simpsons, beer-swilling Homer falls in love with a sandwich. He spends his days nibbling away at the “sickening, festering remains of a 10-foot hoagie,” Nathan Rabin writes, “long after decency, self-respect, and survival would all seem to dictate throwing it out.” The sandwich may be yet another instance of the show pulling some obscure detail from American history for comic effect — or maybe writer David M. Stern read Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, in which the playwright describes “an old desiccated ruin of dust-laden bread and mummified ham or cheese.”

O’Neill’s sandwich is so historical, it has a name, the Raines Sandwich, named after New York State Senator John Raines, the author of an 1896 law that raised the cost of liquor licenses substantially, upped the drinking age from sixteen to eighteen, and banned alcoholic beverages on Sundays except in large hotels and lodging houses which served a complimentary meal with their drinks. The law targeted working people and their one day of respite, and it hit bar owners hard. “After all,” writes the Irish Examiner, “labourers mostly worked six days a week, with Sunday their only full day for drinking, and Sunday was the most profitable day for saloons.”

The complimentary-meal-with-drinks mandate, as it were, was designed so that wealthy patrons at luxury hotels could drink on Sundays, but low-rent saloon owners seized on the loophole, transforming dive bars into rooming houses overnight with tablecloths and “alleged bedrooms” made from attics and basements. “It was then that the loosest possible definition of a ‘substantial meal’ became the Raines Sandwich.” The sandwich might be made of anything, even a brick between two slices of bread; it was rarely eaten. Sometimes, it would be served to a guest with their beer or whiskey, then whisked away and given to someone else. A single Raines Sandwich might last the day, or even the whole week.

Some establishments tried to get away with serving crackers and moldy cheese alone (stalwart New York Irish pub McSorley’s gave away crackers, cheese, and onions — a dish for which they now charge). But the courts required a sandwich, at the very least to be served, and the city enforced the law with righteous vigor — thanks in large part to a young Theodore Roosevelt. As Darrell Hartman writes at Atlas Obscura, New York Republicans in Albany “spoke for a constituency largely comprised of rural small-town churchgoers” worried about urban vice. But Raines had a city ally in Roosevelt, then a “37-year-old firebrand… pushing a law-and-order agenda as president of the city’s newly organized police commission.”

Roosevelt canvassed the Lower East Side with patrolman Frank Rathgeber, sending him into saloons in plain clothes to investigate. “Rathgeber said he saw many sandwiches but only one bed,” writes author Richard Zacks in Island of Vice. The sandwiches were moldy, and were taken away uneaten. “He never was asked to buy a second sandwich” with subsequent drinks, “or even to eat the first one.” Despite the reform crackdowns, the shady business of the Raines Sandwich let saloon owners skirt the law until it was repealed, finally, in 1924. As Hartman notes, behind the purported good intentions of the Temperance movement lay a determined culture war:

Those in favor of the Sunday ban, generally middle-class and Protestant, saw it as a cornerstone of social improvement. For those against, including the city’s tide of German and Irish immigrants, it was an act of repression—an especially spiteful one because it limited how the average laborer could enjoy himself on his one day off. The Sunday ban was not popular, to say the least, among the city’s Jews, who’d already observed their Sabbath the day before.

The Raines Law was as much about enforcing religious observance and cultural conformity on immigrants as it was an attempt to combat crime, poverty, and violence in the city. Those whose beliefs did not prevent them from enjoying themselves on Sunday saw no reason to take the law any more seriously than they would a rotting week-old sandwich or a brick between two slices of moldy bread.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Explore Thousands of Free Vintage Cocktail Recipes Online (1705–1951)

The First Known Photograph of People Sharing a Beer (1843)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness