Surfing is generally believed to have originated in Hawaii and will be forever associated with the Polynesian islands. Yet anthropologists have found evidence of something like surfing wherever humans have encountered a beach — on the coasts of West Africa, in the Caribbean, India, Syria, and Japan. Surfing historian Matt Warshaw sums up the problem with locating the origins of this human activity: “Riding waves simply for pleasure most likely developed in one form or another among any coastal people living near warm ocean water.” Could one make a similar point about skiing?

It seems that wherever humans have settled in places covered with snow for much of the year, they’ve improvised all kinds of ways to travel across it. Who did so with the first skis, and when? Ski-like objects dating from 6300–5000 BC have been found in northern Russia. A New York Times article recently described evidence of Stone Age skiers in China. “If skiing, as it seems possible,” Nils Larsen writes at the International Skiing History Association, “dates back 10,000 years or more, identifying a point of origin (or origins) will be difficult at best.” Such discussions tend to get “bogged down in politics and national pride,” Larsen writes. For example, “since the emergence of skiing in greater Europe in the late 1800s” — as a sport and purely recreational activity — “Norway has often been considered the birthplace of skiing. Norway has promoted this view and it is a point of national pride.”

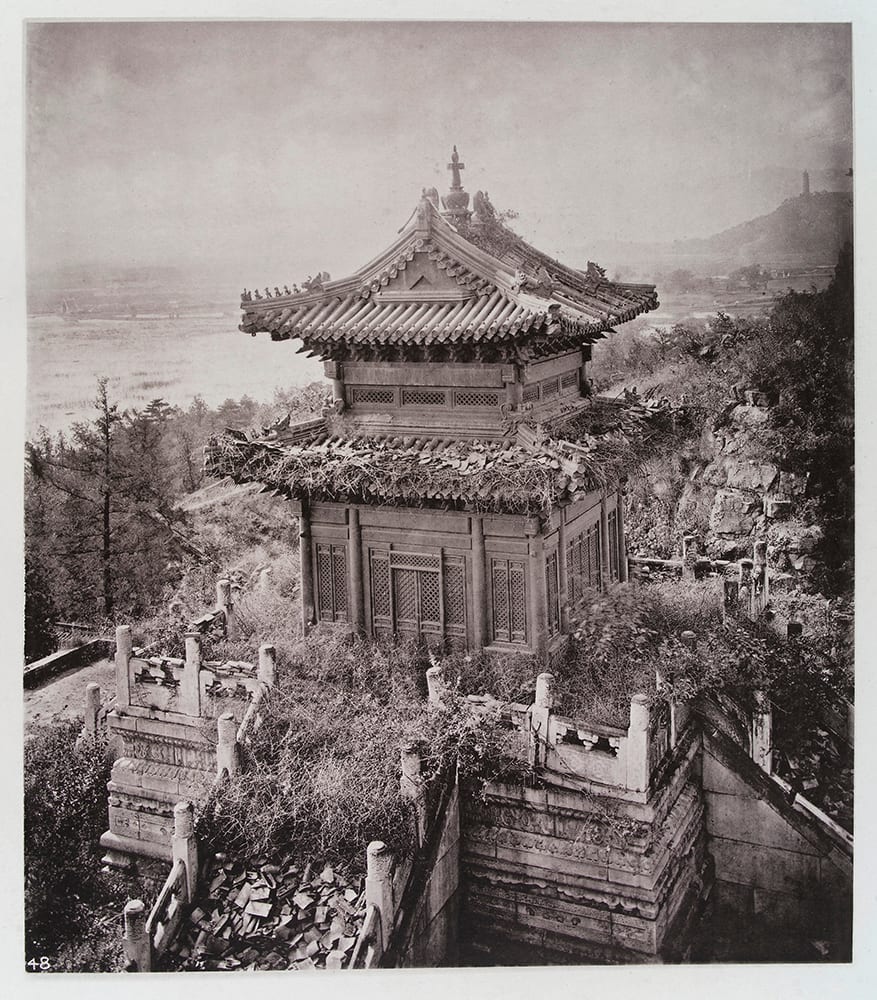

Despite its earliest records of skiing dating millennia later than other regions, Norway has some claim. The word ski is, after all, Norwegian, derived from Old Norse skíð, meaning “cleft wood” or “stick.” And the best-preserved ancient skis ever found have been discovered in a Norwegian ice field. “Even the bindings are mostly intact,” notes Kottke. The first ski, believed to be 1300 years old, turned up in 2014, found by the Glacier Archeology Program (GAP) in the mountains of Innlandet County, Norway. The archaeologists decided to wait, let the ice melt, and see if the other ski would appear. It did, just recently, and in the video above, you can watch the researchers pull it from the ice.

Photo: Andreas Christoffer Nilsson, secretsoftheice.com

“Measuring about 74 inches long and 7 inches wide,” notes Livia Gershon at Smithsonian, “the second ski is slightly larger than its mate. Both feature raised footholds. Leather straps and twisted birch bark bindings found with the skis would have been attached through holes in the footholds. The new ski shows signs of heavy wear and eventual repairs.” The two skis are not identical, “but we should not expect them to be,” says archaeologist Lars Pilø. “The skis are handmade, not mass-produced. They have a long and individual history of wear and repair before an Iron Age skier used them together and they ended up in the ice.”

The new ski answered questions the researchers had about the first discovery, such as how the ancient skis might have maintained forward motion uphill. “A furrow on the underside along the length of the ski, as you find on other prehistoric skis (and on modern cross-country skis), would solve the question,” they write, and the second ski contained such a furrow. While they may never prove that Norway invented skiing, as glacier ice melts and new artifacts appear each year, the team will learn much more about ancient Norwegian skiers and their way of life. See their current discoveries and follow their future progress at the Secrets of the Ice website and on their YouTube channel.

Related Content:

Archaeologists Find the Earliest Work of “Abstract Art,” Dating Back 73,000 Years

Medieval Tennis: A Short History and Demonstration

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness