I’m sitting on the balcony

Reading Flannery O’Connor

With a pencil and a plan- Nick Cave, Carnage

Access to technology has transformed the creative process, and many artists who’ve come to depend on it have long ceased to marvel at the labor and time saved, seething with resentment when devices and digital access fails.

Musician Nick Cave, founder and frontman of The Bad Seeds, is one who hasn’t abandoned his analog ways, whether he’s in the act of generating new songs, or seeking respite from the same.

“There has always been a strong, even obsessive, visual component to the (songwriting) process,” he writes, “a compulsive rendering of the lyric as a thing to be seen, to be touched, to be examined:”

I have always done this—basically drawn my songs—for as long as I’ve been writing them…when the pressure of song writing gets too much, well, I draw a cute animal or a naked woman or a religious icon or a mythological creature or something. Or I take a Polaroid or make something out of clay. I do a collage, or write a child’s poem and date stamp and sticker it, or do some granny-art with a set of watercolour paints.

Last year, these extra creative labors became fruits in their own right, with the opening of Cave Things, an online shop well stocked with quirky objects “conceived, sourced, shaped, and designed” by the musician.

These include such longtime fascinations as prayer cards, picture discs, and Polaroids, and a series of enameled charms and ceramic figures that evoke Victorian Staffordshire “flatbacks.”

T‑shirts, guitar picks and egg cups may come graced with doodles of frequent collaborator Warren Ellis’ bearded mug, or the aforementioned naked women, which Cage describes to Interview’s Ben Barna as “a compulsive habit I have had since my school days”:

They have no artistic merit. Rather, they are evidence of a kind of ritualistic and habitual thinking, not dissimilar to the act of writing itself, actually.

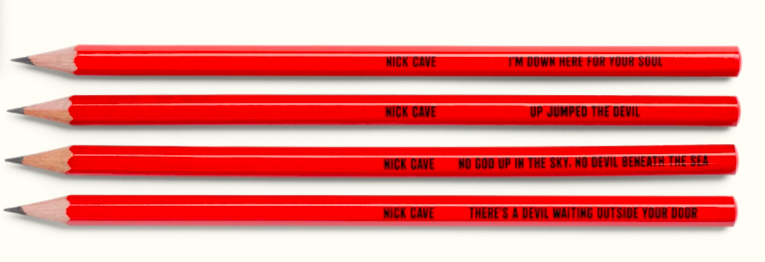

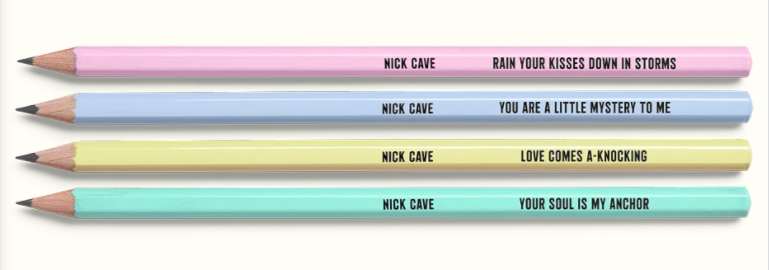

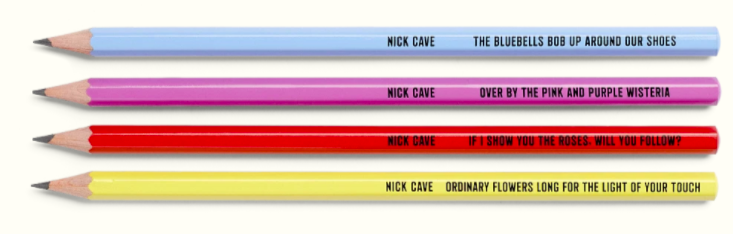

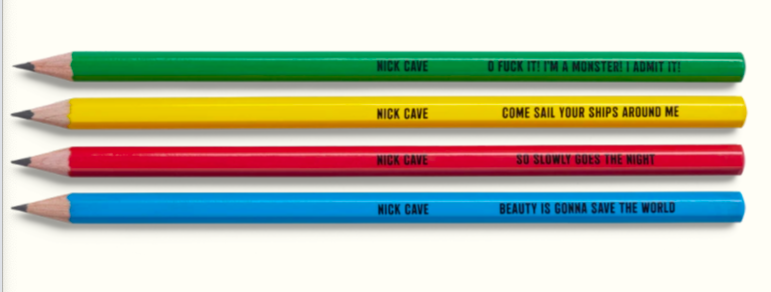

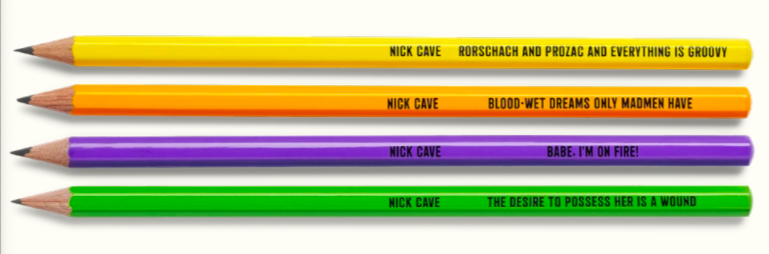

Of all of Cave’s Cave Things, the ones with the broadest appeal may be the pencil sets personalized with thematic snippets of his lyrics.

White god pencils quote from “Into My Arms,” “Idiot Prayer,” “Mermaids,” and “Hand of God.”

A red devil pencil bearing lines from “Brompton Oratory” slips a bit of god into the mix, as well as a reference to the sea, a frequent Cave motif.

Madness and war pencils are counterbalanced by pencils celebrating love and flowers.

The pencils are Vikings, a classic Danish brand well known to pencil nerds, hard and black on the graphite scale.

Put them all in a cup and draw one out at random, or let your mood or feelings about what said pencil will be writing or drawing determine your pick.

Meanwhile Cave’s implements of choice may surprise you. As he told NME’s Will Richards last December:

My process of lyric writing is as follows: For months, I write down ideas in a notebook with a Bic medium ballpoint pen in black. At some point, the songs begin to reveal themselves, to take some kind of form, which is when I type the new lyrics into my laptop. Here, I begin the long process of working on the words, adding verses, taking them away, and refining the language, until the song arrives at its destination. At this stage, I take one of the yellowing back pages I have cut from old second-hand books, and, on my Olympia typewriter, type out the lyrics. I then glue it into my bespoke notebook, number it, date-stamp it, and sticker it. The song is then ‘officially’ completed.

Hmm. No pencils, though there’s a reference to a blind pencil seller in Cave’s contribution to the soundtrack of Wim Wenders’ science fiction epic Until the End of the World.

Two more lyrics about pencils and he’ll have enough to put a Pencil Pencils set up on Cave Things!

Follow Cave Things on Instagram to keep tabs on new pencil drops.

Related Content:

Listen to Nick Cave’s Lecture on the Art of Writing Sublime Love Songs (1999)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.