American inventors never met a phenomenon — natural, manmade, or otherwise — they couldn’t try to patent. From impossible technologies to possible evidence of aliens visiting planet Earth, everything’s fair game if you can sell the idea. After highly-publicized UFO sightings in Washington State and Roswell, New Mexico, for example, patents for flying saucers began pouring into government offices. “As soon as there was a popular ‘spark,’” writes Ernie Smith at Atlas Obscura, “the saucer was everywhere.” It received its own classification in the U.S. Patent Office, with the indexing code B64C 39/001, for “flying vehicles characterized by sustainment without aerodynamic lift, often flying disks having a UFO-shape.”

Google Patents lists “around 192 items in this specific classification,” with surges in applications between 1953–56, 1965–71, and an “unusually dramatic surge… between 2001 and 2004.” Make of that what you will. The story of the UFO gets both stranger and more mundane when we learn that Alexander Weygers, the very first person to file a patent for such a flying vehicle, invented it decades before UFO-mania and patented it in 1945. He was not an American inventor but the Indonesian-born son of a Dutch sugar plantation family. He learned blacksmithing on the farm, received an education in Holland in mechanical engineering and naval architecture, and honed his mechanical skills while taking long sea voyages alone.

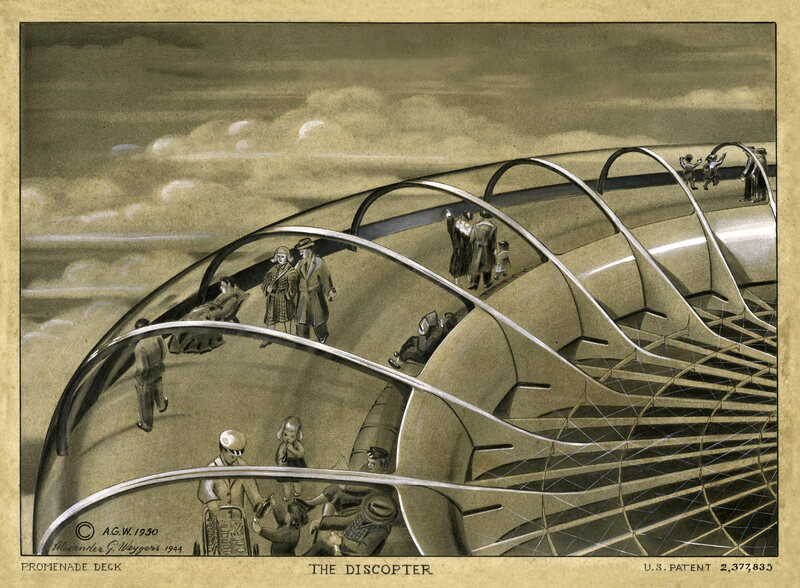

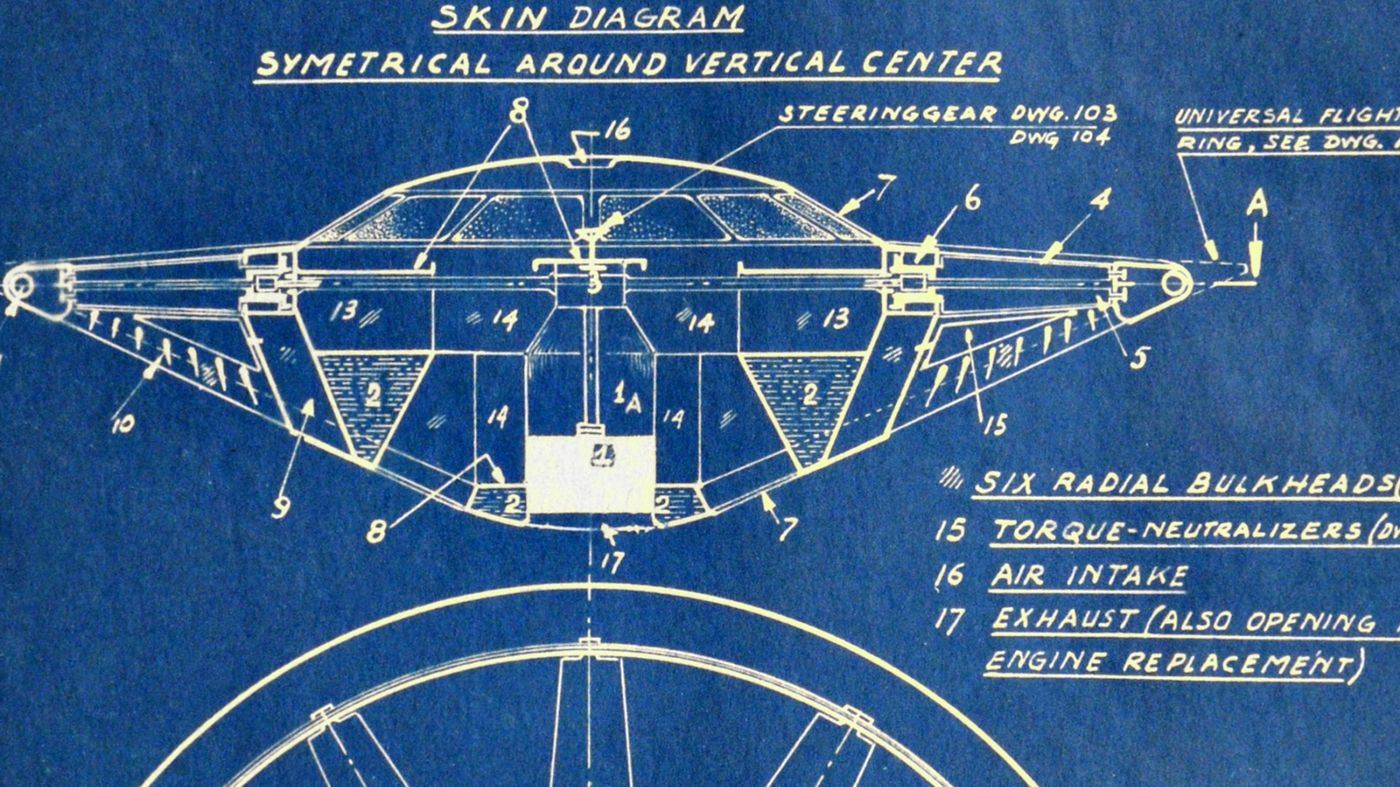

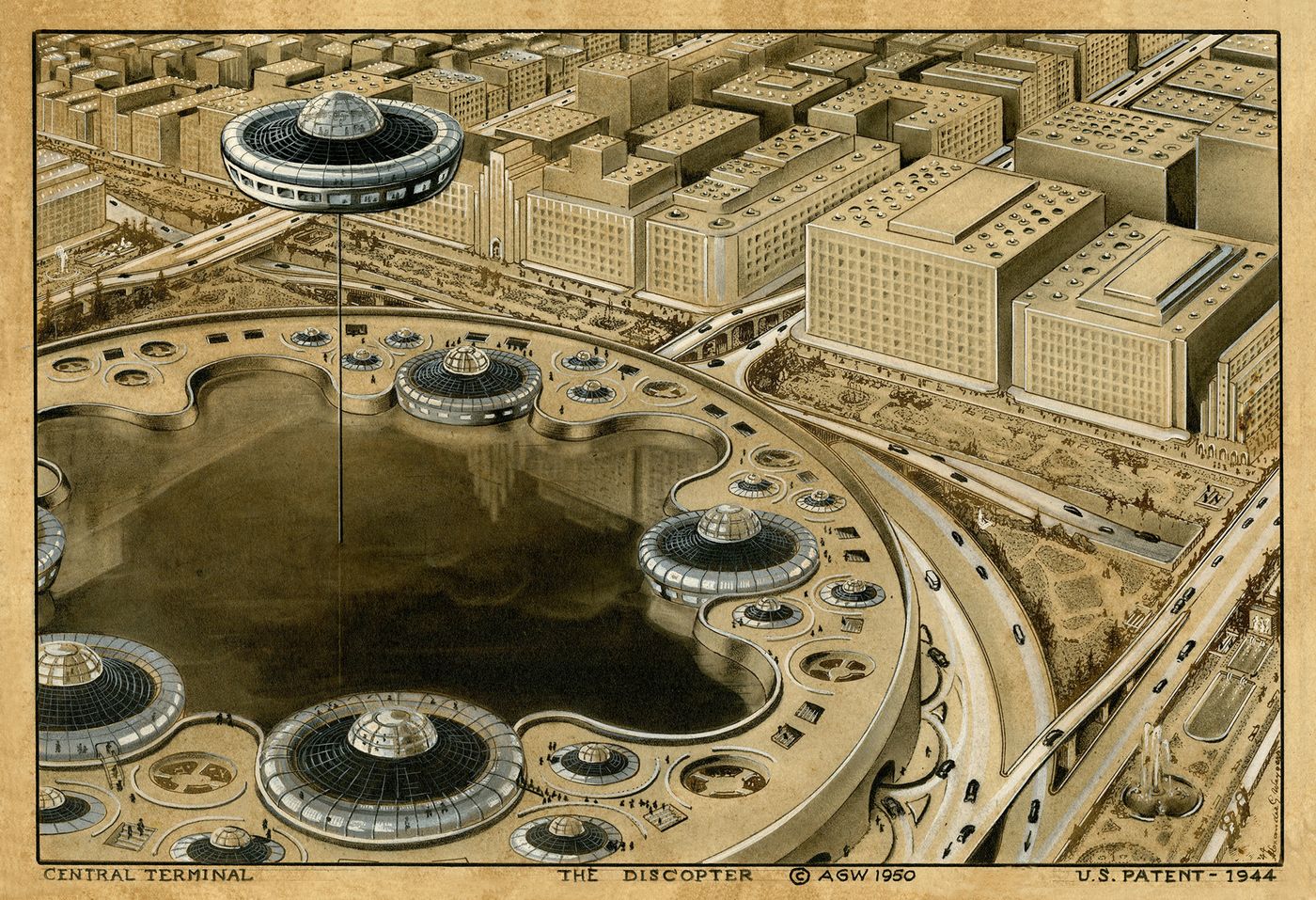

In 1926, Weygers and his wife Jacoba Hutter moved to Seattle, Ashlee Vance writes at Bloomberg Businessweek, “where he pursued a career as a marine engineer and ship architect and began inking drawings of the Discopter” — the flying-saucer-like vehicle he would patent after working for many years as a painter and sculptor, mourning the death of his wife, who died in childbirth in 1928. By the time Weygers was ready to revive the Discopter, the time was ripe, it seems, for a wave of technological convergent evolution — or a technological theft. Perhaps, as Weygers’ claimed, UFOs really were Army test planes: test pilots flying something based on the inventor’s design — which was not a UFO, but an attempt at a better helicopter.

Sightings of strange objects in the sky did not begin in 1947. “Tales of mysterious flying objects date to medieval times,” Vance writes, “and other inventors and artists had produced images of disk-shaped crafts. Henri Coanda, a Romanian inventor, even built a flying saucer in the 1930s that looked similar to what we now think of as the classic craft from outer space. Historians suspect that the designs of Coanda and Weygers, floating around in the public sphere, combined with the postwar interest in sci-fi technology to create an atmosphere that gave rise to a sudden influx of UFO sightings.” In the 1950s, NASA and the U.S. Navy even began testing vertical takeoff vehicles that looked suspiciously like the patented Discopter.

Weygers was livid and “convinced his designs had been stolen.” The press even picked up the story. In 1950 the San Francisco Chronicle ran an article headlined “Carmel Valley Artist Patented Flying Saucer Five Years Ago: ‘Discopter’ May Be What People Have Seen Lately.” Although Weygers never built a Discopter himself, the article goes on to note that “the invention became the prototype for all disk-shaped vertical take-off aircraft since built by the U.S. armed forces and private industry, both here and abroad.” Just how many such vehicles have been constructed, and have actually been air-worthy, is impossible to say.

Smith surveys many of the patents for flying saucers filed over the past 75 years by both individuals and large companies. In the latter category, we have companies like Airbus and startups created by Google co-founder Larry Page currently working on flying saucer-like designs. The history of such vehicles may not provide sufficient evidence to disprove UFO sightings, but it may one day lead to the technology for flying cars we thought would already have arrived this far into the space age. For that we have to thank, though he may never get the credit, the modern Renaissance artist and inventor Alexander Weygers.

Related Content:

Carl Jung’s Fascinating 1957 Letter on UFOs

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness