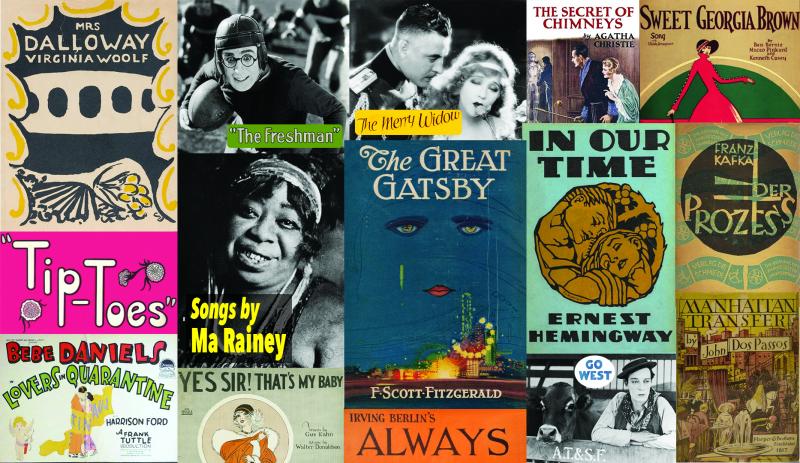

“The year 1925 was a golden moment in literary history,” writes the BBC’s Jane Ciabattari. “Ernest Hemingway’s first book, In Our Time, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby were all published that year. As were Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer, Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy and Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith, among others.” In that year, adds Director of Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain Jennifer Jenkins, “the stylistic innovations produced by books such as Gatsby, or The Trial, or Mrs. Dalloway marked a change in both the tone and the substance of our literary culture, a broadening of the range of possibilities available to writers.”

In the year 2021, no matter what area of culture we inhabit, we now find our own range of possibilities broadened. Works from 1925 have entered the public domain in the United States, and Duke University’s post rounds up more than a few notable examples. These include, in addition to the aforementioned titles, books like W. Somerset Maugham’s The Painted Veil and Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto’s A Daughter of the Samurai; films like The Freshman and Go West, by silent-comedy masters Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton; and music like Irving Berlin’s “Always” and several compositions by Duke Ellington, including “Jig Walk” and “With You.”

These works’ public-domain status means that, among many other benefits to all of us, the Internet Archive can easily add them to its online library. In addition, writes Jenkins, “HathiTrust will make tens of thousands of titles from 1925 available in its digital repository. Google Books will offer the full text of books from that year, instead of showing only snippet views or authorized previews. Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can afford to publicly perform, or rearrange, the music.” And the creators of today “can legally build on the past — reimagining the books, making them into films, adapting the songs.”

Does any newly public-domained work of 2021 hold out as obvious a promise in that regard as Fitzgerald’s great American novel? Any of us can now make The Great Gatsby “into a film, or opera, or musical,” retell it “from the perspective of Myrtle or Jordan, or make prequels and sequels,” writes Jenkins. “In fact, novelist Michael Farris Smith is slated to release Nick, a Gatsby prequel telling the story of Nick Carraway’s life before he moves to West Egg, on January 5, 2021.” Whatever results, it will further prove what Ciabattari calls the “continuing resonance” of not just Jay Gatsby but all the other major characters created by the novelists of 1925, inhabitants as well as embodiments of a “transformative time” who are “still enthralling generations of new readers” — and writers, or for that matter, creators of all kinds.

Related Content:

Free: The Great Gatsby & Other Major Works by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black, Starring a 19-Year-old Billie Holiday

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.