Purveyors of the shocking, primal idiocy of pure rock and roll can in many cases be some of the most intelligent people in pop. Or at least that’s the case with the king of shocking, primal idiocy, Iggy Pop. He has interpreted Whitman’s “barbaric yawp” and delivered the John Peel Lecture for BBC Music, becoming “a visiting professor from the School of Punk Rock Hard Knocks,” writes Rolling Stone and bringing an elder statesman’s perspective informed not only by his years in the bowels of the music industry but also by his avocation as a scholar of the Roman Empire….

Yes, that’s right, Iggy Pop is not only an adroit stylist of some of the most brilliantly stupid garage rock ever made, but he’s also a serious reader and thinker who once published a brief reflection on his relationship with Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in the academic journal Ireland Classics.

“Iggy Pop, like Bob Dylan,” writes E.J. Hutchinson, “has an avid interest in Roman antiquity and its genetic connection to contemporary life.” He may also be the sharpest, wiliest embodiment of post-industrial American decline—his entire musical personality a punch in the collective face of the nation’s delusions.

In 1982, horrified by the meanness, tedium and depravity of my existence as I toured the American South playing rock and roll music and going crazy in public, I purchased an abridged copy of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Dero Saunders, Penguin).

The grandeur of the subject appealed to me, as did the cameo illustration of Edward Gibbon, the author, on the front cover. He looked like a heavy dude.

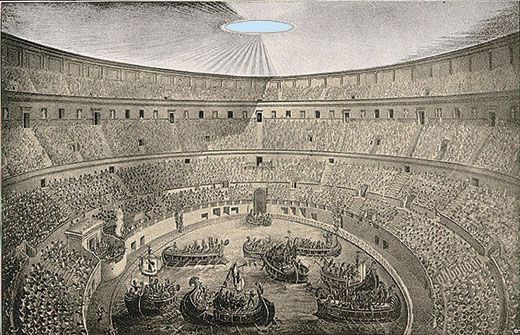

Hutchinson gives us a finely wrought analysis of Pop’s “tour de force of classical Gibbonian English prose, a scrap of Ciceronian periodicity.” (Gibbon did, indeed, look like a heavy dude.) Pop’s reading of Gibbon, “with pleasure around 4 am, with my drugs and whisky in cheap motels,” absorbed him in its “clash of beliefs, personalities and values,” he writes, “played out on antiquity’s stage by crowds of the vulgar, led by huge archetypal characters.” All of this appealed to him, he writes, given his own role in “a political business… the music business, which is not about music at all, but is a kind of religion-rental.”

Gibbon’s massive saga, a monumental example of sweeping Enlightenment historiography, so captivated Pop that a decade later, it inspired “an extemporaneous soliloquy” he called “Caesar,” the closing track on 1993’s “overlooked masterpiece” American Caesar. The spoken word piece “made me laugh my ass off,” he writes, “because it was so true. America is Rome. Of course, why shouldn’t it be? All of Western life and institutions today are traceable to the Romans and their world. We are all Roman children for better or worse.”

But there was much more to Pop’s reading of Gibbon—which he eventually enjoyed in a “beautiful edition in three volumes of the magnificent original unabridged”—than a possibly facile comparison between one failing empire and another. Much more, indeed. Reading Gibbon, he writes (sounding very much like another proponent of the classics, Italo Calvino), taught him how to think about the present, and how to think, humbly, about himself. He ends his essay with a numbered list of “just some of the ways I benefit”:

- I feel a great comfort and relief knowing that there were others who lived and died and thought and fought so long ago; I feel less tyrannized by the present day.

- I learn much about the way our society really works, because the system-origins — military, religious, political, colonial, agricultural, financial — are all there to be scrutinized in their infancy. I have gained perspective.

- The language in which the book is written is rich and complete, as the language of today is not.

- I find out how little I know.

- I am inspired by the will and erudition which enabled Gibbon to complete a work of twenty-odd years. The guy stuck with things. I urge anyone who wants life on earth to really come alive for them to enjoy the beautiful ancestral ancient world.

Read Pop’s full 1995 Ireland Classics essay on Jstor or Medium.

via Hannah Rose Woods

Related Content:

Prof. Iggy Pop Delivers the BBC’s 2014 John Peel Lecture on “Free Music in a Capitalist Society”

The Splendid Book Design of the 1946 Edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Iggy Pop Reads Walt Whitman in Collaborations With Electronic Artists Alva Noto and Tarwater

Iggy Pop Reads Edgar Allan Poe’s Classic Horror Story, “The Tell-Tale Heart”

Stream Iggy Pop’s Two-Hour Radio Tribute to David Bowie

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness