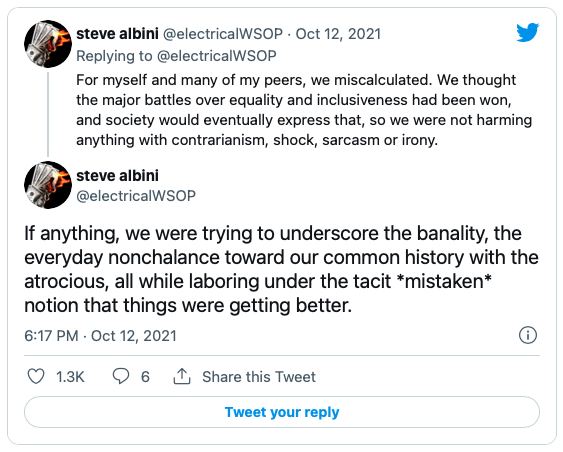

In a recent series of Tweets and a follow-up interview with MEL magazine, legendary alt-rock producer and musician Steve Albini took responsibility for what he saw as his part in creating “edgelord” culture — the jokey, meme-worthy use of racist, misogynist and homophobic slurs that became so normalized it invaded the halls of Congress. “It was genuinely shocking when I realized that there were people in the music underground who weren’t playing when they were using language like that,” he says. “I wish that I knew how serious a threat fascism was in this country…. There was a joke made about the Illinois Nazis in The Blues Brothers. That’s how we all perceived them — as this insignificant, unimportant little joke. I wish that I knew then that authoritarianism in general and fascism specifically were going to become commonplace as an ideology.”

Perhaps, as Stephen Fry explains in the video clip above from his BBC documentary series Planet Word, we might better understand how casual dehumanization leads to fascism and genocide if we see how language has worked in history. The Holocaust, the most prominent but by no means only example of mass murder, could never have happened without the willing participation of what Daniel Goldhagen called “ordinary Germans” in his book Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men, about the Final Solution in Poland, makes the point Fry makes above. Cultural factors played their part, but there was nothing innately Teutonic (or “Aryan”) about genocide. “We can all be grown up enough to know that it was humanity doing something to other parts of humanity,” says Fry. We’ve seen examples in our lifetimes in Rwanda, Myanmar, and maybe wherever we live — ordinary humans talked into doing terrible things to other people.

But no matter how often we encounter genocidal movements, it seems like “a massively difficult thing to get your head around,” says Fry: “how ordinary people (and Germans are ordinary people just like us)” could be made to commit atrocities. In the U.S., we have our own version of this — the history of lynching and its attendant industry of postcards and even more grisly memorabilia, like the trophies serial killers collect. “In each one of these genocidal moments… each example was preceded by language being used again and again and again to dehumanize the person that had to be killed in the eyes of their enemies,” says Fry. He briefly elaborates on the varieties of dehumanizing anti-Semitic slurs that became common in the 1930s, referring to Jewish people, for example, as vermin, apes, untermenschen, viruses, “anything but a human being.”

“If you start to characterize [someone this way], week after week after week after week,” says Fry, citing the constant radio broadcasts against the Tutsis in the Rwandan genocide, “you start to think of someone who is slightly sullen and disagreeable and you don’t like very much anyway, and you’re constantly getting the idea that they’re not actually human. Then it seems it becomes possible to do things to them we would call completely unhuman, and inhuman, and lacking humanity.” While it’s absolutely true, he says, that language “guarantees our freedom” through the “free exchange of ideas,” it can really only do that when language users respect others’ rights. When, however, we begin to see “special terms of insult for special kinds of people, then we can see very clearly, and history demonstrates it time and time again, that’s when ordinary people are able to kill.”

Related Content:

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness