When westerners first discovered the work of Japanese woodcut artist Katsushika Hokusai, it was primarily through his late-career print The Great Wave off Kanagawa and the series from which it came, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, after the opening of Japan to international trade and the mass consumption of Japanese art in the late 19th century. Impressionists like Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh went wild for Japanese prints; Claude Debussy composed La mer; artists, artisans, and architects on both sides of the Atlantic fell for all things Japonisme.

Hokusai died in 1849 and did not live to see this newfound international admiration. When he completed The Great Wave, he was in his seventies — a master of his craft who had himself absorbed significant influence from western painters.

During his “formative experience of European art,” John-Paul Stonard writes at The Guardian, Hokusai “learnt from European prints brought into Japan by Dutch traders.” He took these lessons in directions all his own, however. His Mount Fuji prints “could not have been further from anything being made in Europe at the time.”

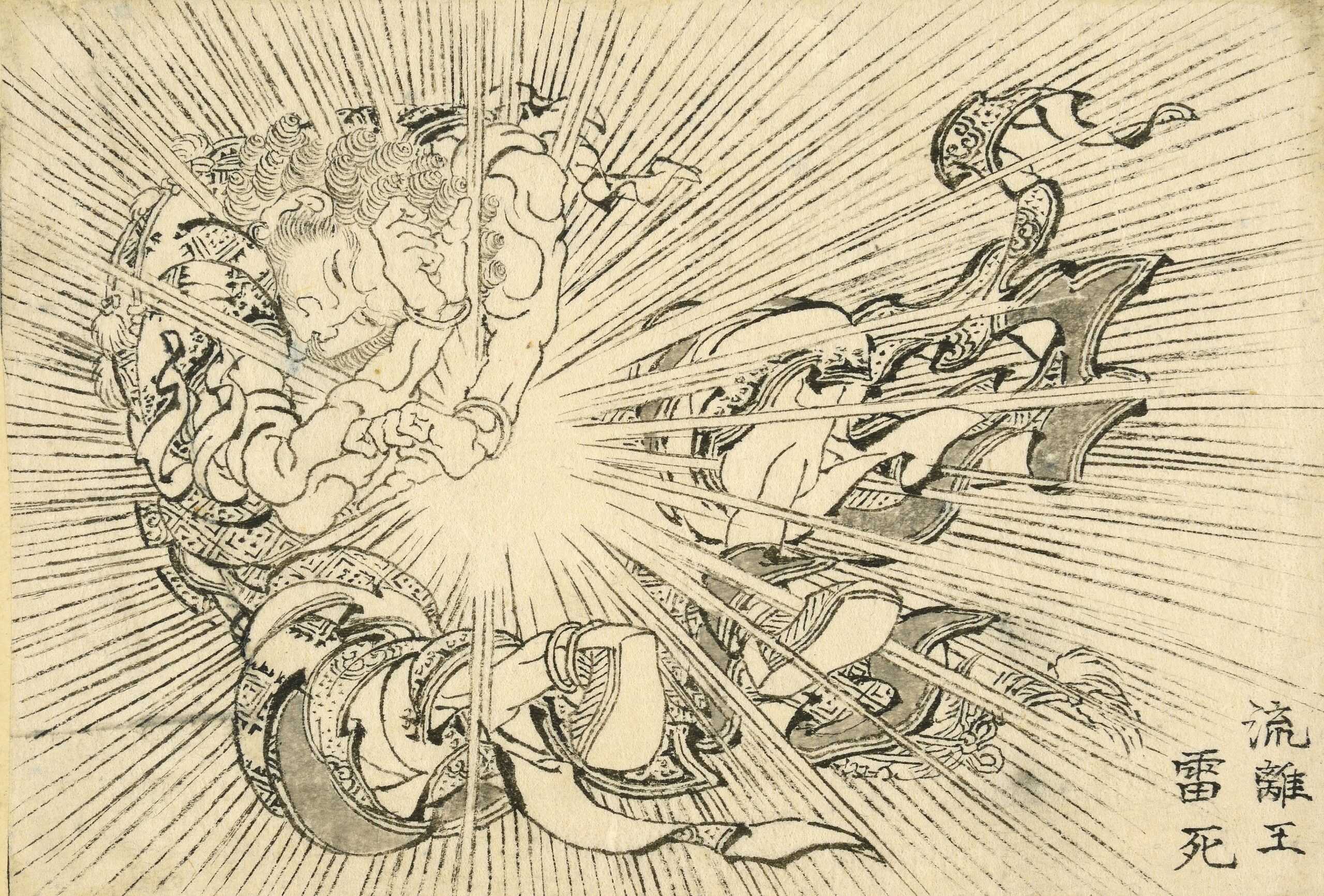

Hokusai’s European and American enthusiasts saw only the barest glimpse of his body of work, which we can now fully appreciate in exhibitions in person and online. And we can now appreciate a series of drawings that have been hidden away for over seventy years and were hardly seen at all in the 200 years since their creation. Made for an unpublished encyclopedia titled Banmotsu eon daises zu (The Great Picture Book of Everything), “The drawings were long thought forgotten,” Valentina Di Liscia writes at Hyperallergic, “last recorded at an auction in Paris in 1948 before they resurfaced in 2019.”

Made sometime between 1820 and the 1840s, “the meticulous, postcard-sized works are known as hanshita‑e, a term for the final drawings used to carve the key blocks in Japanese woodblock printing.” These are usually destroyed in the process, but since the prints were never made, for reasons unknown, “the delicate illustrations remained intact, mounted on cards and stored in a custom-made wooden box.” The drawings depict everything from “the typical inhabitants of lands in East, Southeast, and Central Asian and beyond” to one of the 33 manifestations of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, “Dragon head Kannon.”

At the top, curator Alfred Haft walks us through his favorite drawings from the set, and you can see all 103 of the diminutive illustrations online at the British Museum. Formerly owned by the collector and Art Nouveau jeweler Henri Vever, the prints could have inspired many a western artist, but it seems they were hidden away and have been seen by very few eyes. Discover them yourself for the first time here.

Related Content:

Hokusai’s Iconic Print, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” Recreated with 50,000 LEGO Bricks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness