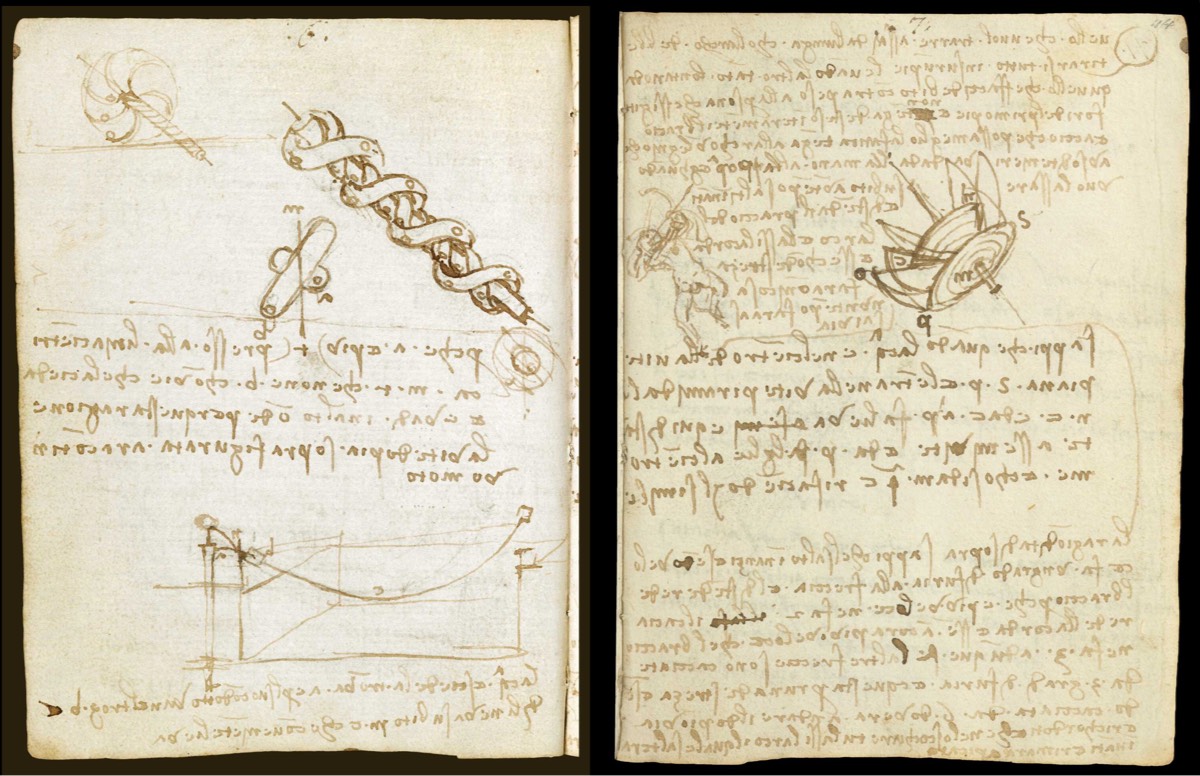

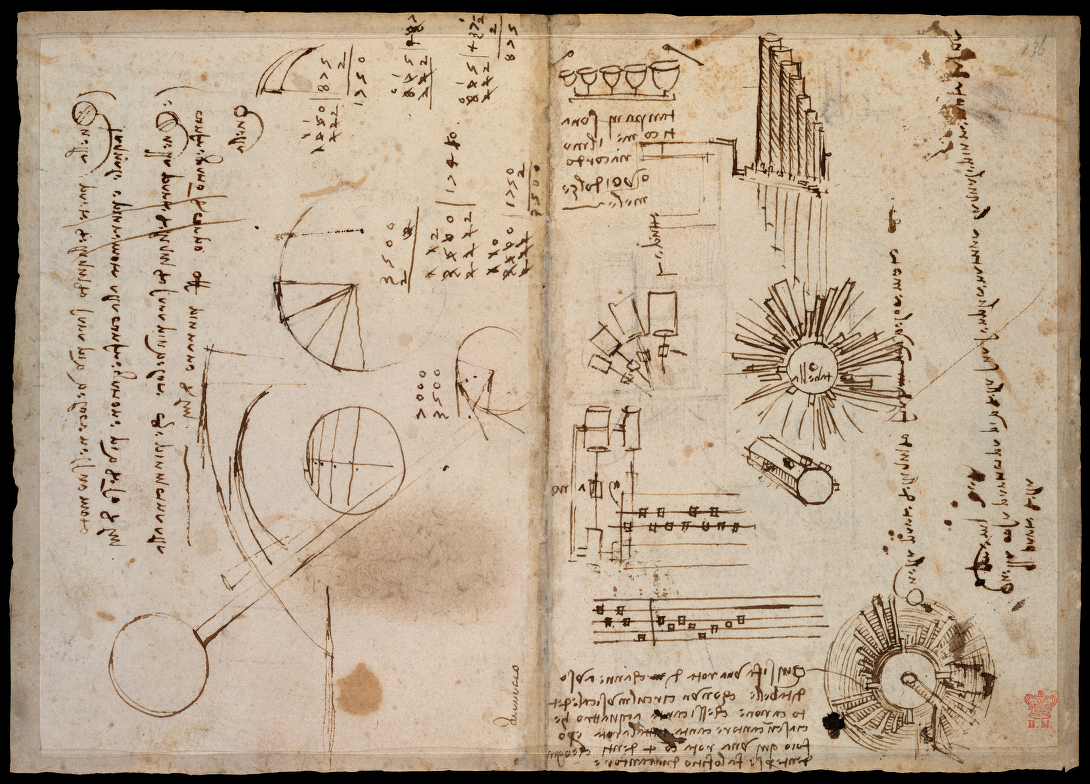

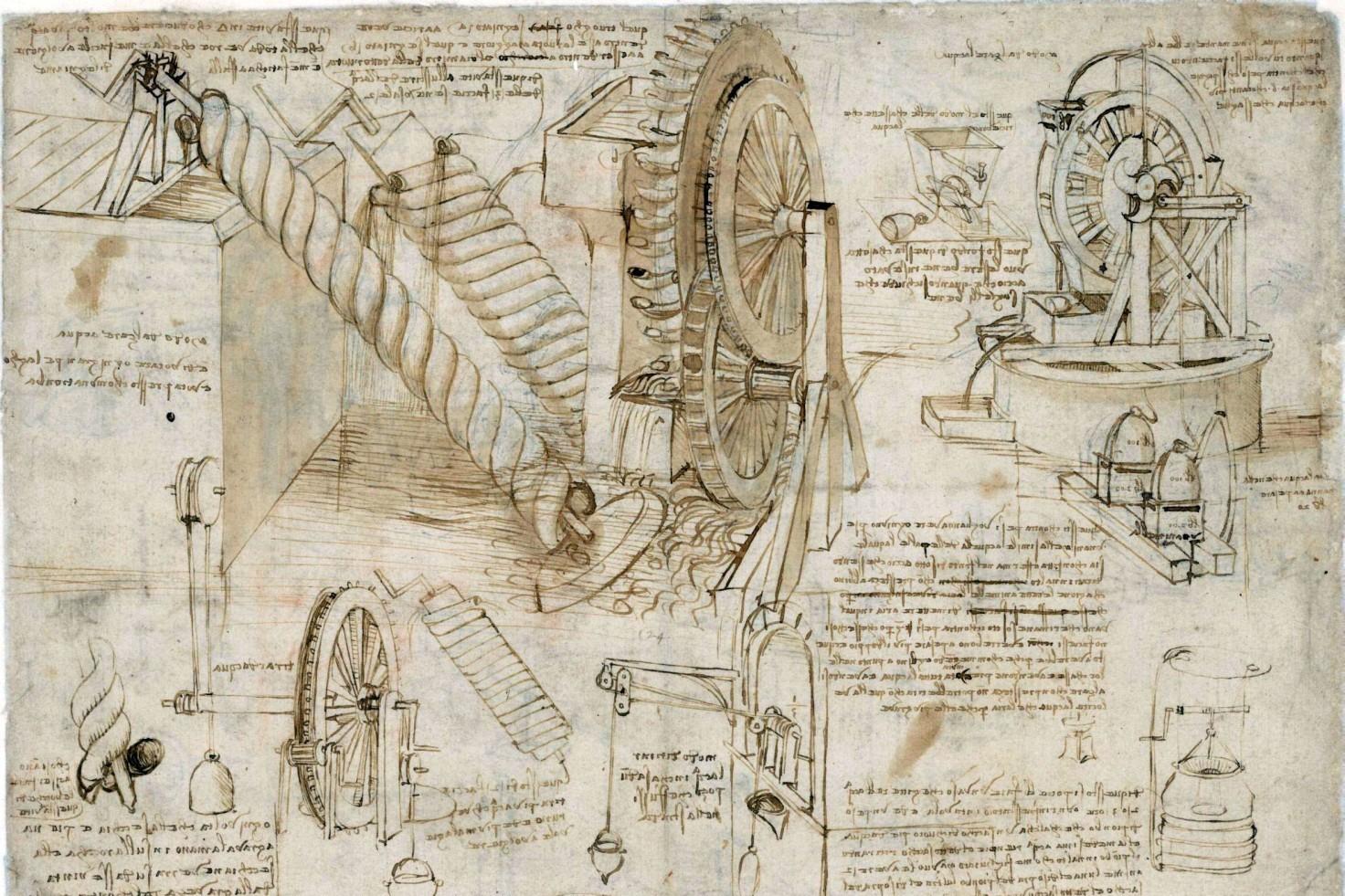

From the hand of Leonardo da Vinci came the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, among other art objects of intense reverence and even worship. But to understand the mind of Leonardo da Vinci, one must immerse oneself in his notebooks. Totaling some 13,000 pages of notes and drawings, they record something of every aspect of the Renaissance man’s intellectual and daily life: studies for artworks, designs for elegant buildings and fantastical machines, observations of the world around him, lists of his groceries and his debtors. Intending their eventual publication, Leonardo left his notebooks to his pupil Francesco Melzi, by the time of whose own death half a century later little had been done with them.

Absent a proper steward, Leonardo’s notebooks scattered across the world. Six centuries later, their surviving pages constitute a series of codices in the possession of such entities as the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the British Museum, the Institut de France, and Bill Gates.

In recent years, they and their collaborating organizations have made efforts to open Leonardo’s notebooks to the world, digitizing them, translating them, and organizing them for convenient browsing on the web. Here on Open Culture, we’ve previously featured the Codex Arundel as made available to the public by the British Library, Codex Atlanticus by the Visual Agency, and the three-part Codex Forster by the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Other collections of Leonardo’s notebooks made available to view online include the Madrid Codices at the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Codex Trivulzianus at the Archivo Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana, and the Codex on the Flight of Birds at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. (Published as a standalone book, his Treatise on Painting is available to download at Project Gutenberg.) Even so, many of the pages Leonardo wrote haven’t yet made it to the internet, and even when they do, generations of interpretive work — well beyond reversing his “mirror writing” — will surely remain. Much as humanity is only now putting some of his inventions to the test, the full publication of his notebooks remains a work in progress. Leonardo himself would surely understand: after all, one can’t cultivate a mind like his without patience.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings

Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (1482)

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To Do List (Circa 1490) Is Much Cooler Than Yours

Why Did Leonardo da Vinci Write Backwards? A Look Into the Ultimate Renaissance Man’s “Mirror Writing”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A superb work on the greatest genius of all time my congratulations, oot, well written, imputable information and very well illustrated

A superb work on the greatest genius of all time my congratulations

Congratulations on your excellent work.