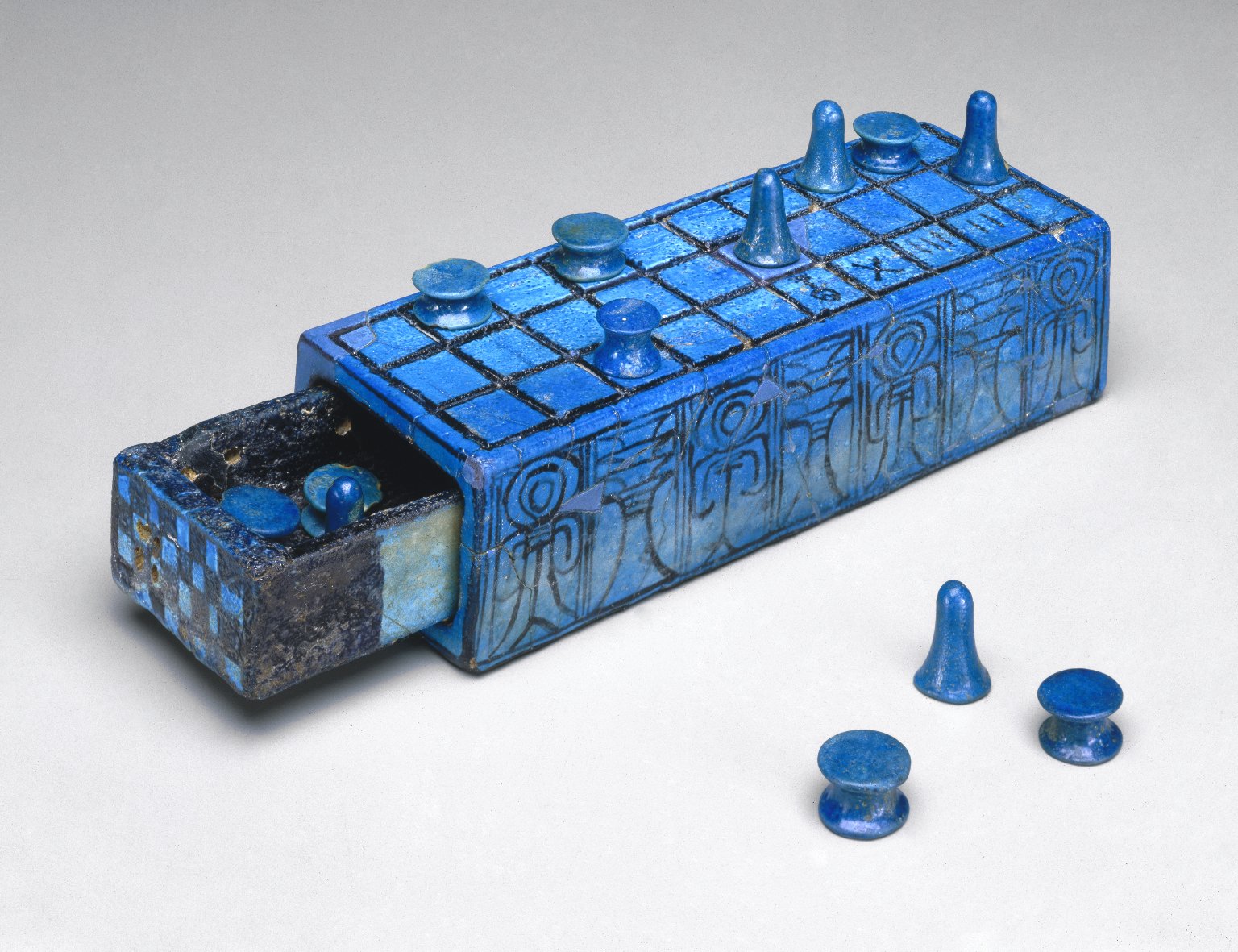

Senet gaming board inscribed for Amenhotep III with separate sliding drawer, via Wikimedia Commons

Games don’t just pass the time, they enact battles of wits, proxy wars, training exercises…. And historically, games are correlated with, if not inseparable from, forms of divination and occult knowledge. We might point to the ancient practice of “astragalomancy,” for example: reading one’s fate in random throws of knucklebones, which were the original dice. Games played with bones or dice date back thousands of years. One of the most popular of the ancient world, the Egyptian Senet, may not be the oldest known, but it could be “the original board game of death,” Colin Barras writes at Science, predating the Ouija board by millennia.

Beginning as “a mere pastime,” Senet evolved “over nearly 2 millennia… into a game with deep links to the afterlife, played on a board that represented the underworld.” There’s no evidence the Egyptians who played around 5000 years ago believed the game’s dice rolls meant anything in particular.

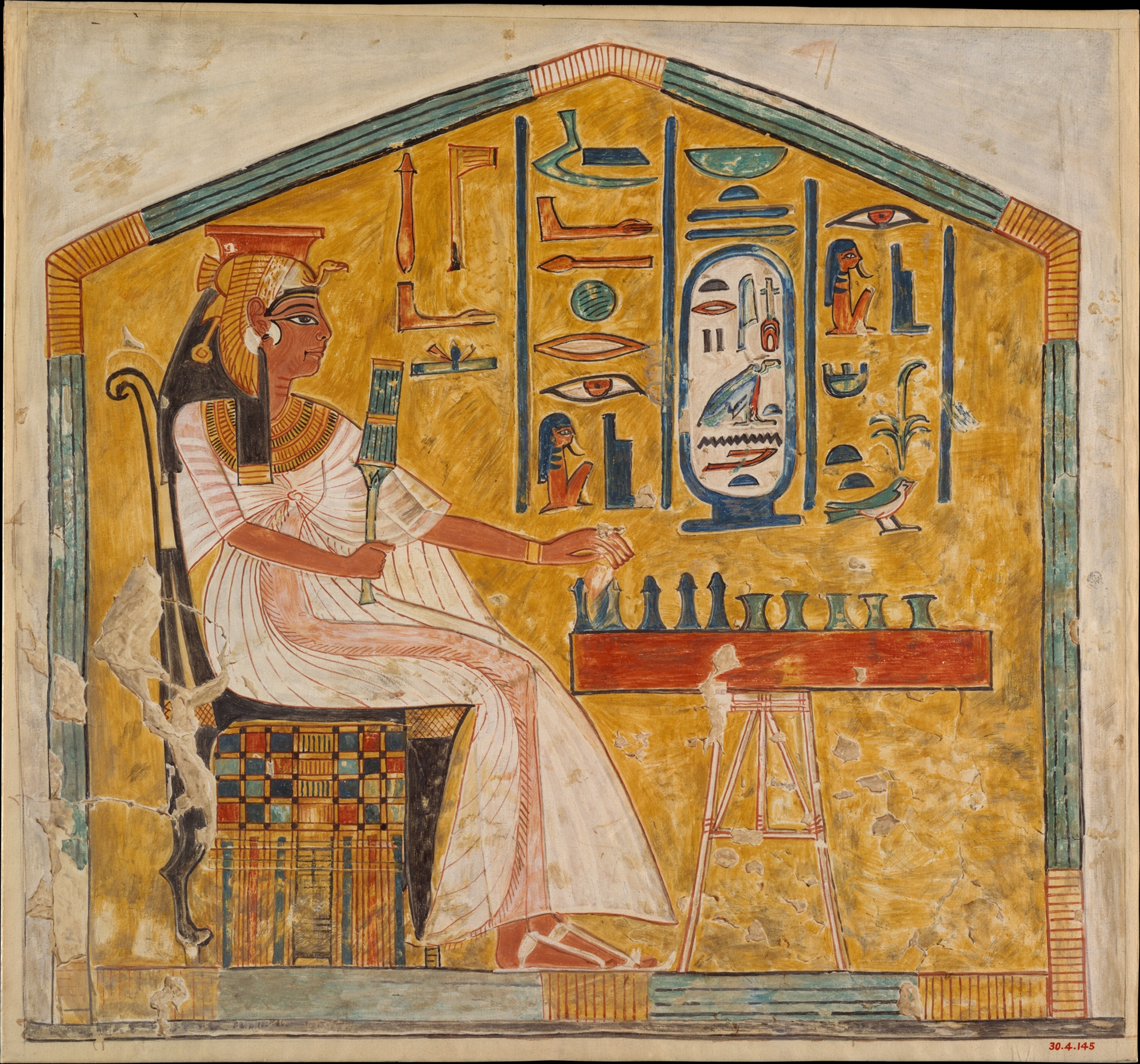

Over the course of a few hundred years, however, images of Senet began appearing in tombs, showing the dead playing against surviving friends and family. “Texts from the time suggest the game had begun to be seen as a conduit through which the dead could communicate with the living” through moves over a grid of 30 squares arranged in three rows of ten.

Facsimile copy of ca. 1279–1213 B.C. painting of Queen Nefertiti playing Senet, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Beloved by such luminaries as the boy pharaoh Tutankhamun and Queen Nefertari, wife of Ramesses II,” Meilan Solly notes at Smithsonian, Senet was played on “ornate game boards, examples of which still survive today.” (Four boards were found in Tut’s tomb.) “Those with fewer resources at their disposal made do with grids scratched on stone surfaces, tables or the floor.” As the game became a tool for glimpsing one’s fate, its last five spaces acquired hieroglyphics symbolizing “special playing circumstances. Pieces that landed in square 27’s ‘waters of chaos,’ for example, were sent all the way back to square 15 — or removed from the board entirely,” sort of like hitting the wrong square in Chutes and Ladders.

Senet gameplay was complicated. “Two players determined their moves by throwing casting sticks or bones,” notes the Met. The object was to get all of one’s pieces across square 30 — each move represented an obstacle to the afterlife, trials Egyptians believed the dead had to endure and pass or fail (the game’s name itself means “passing”). “Because of this connection, senet was not just a game; it was also a symbol for the struggle to obtain immortality, or endless life,” as well as a means of understanding what might get in the way of that goal.

The game’s rules likely changed with its evolving purpose, and might have been played several different ways over the course 2500 years or so. As Brandeis University professor Jim Storer notes in an explanation of possible gameplay, “the exact rules are not known; scholars have studied old drawings to speculate on the rules” — hardly the most reliable guide. If you’re interested, however, in playing Senet yourself, resurrecting, so to speak, the ancient tradition for fun or otherwise, you can easily make your own board. Storer’s presentation of what are known as Jequier’s Rules can be found here. For another version of Senet play, see the video above from Egyptology Lessons.

Related Content:

A Brief History of Chess: An Animated Introduction to the 1,500-Year-Old Game

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness