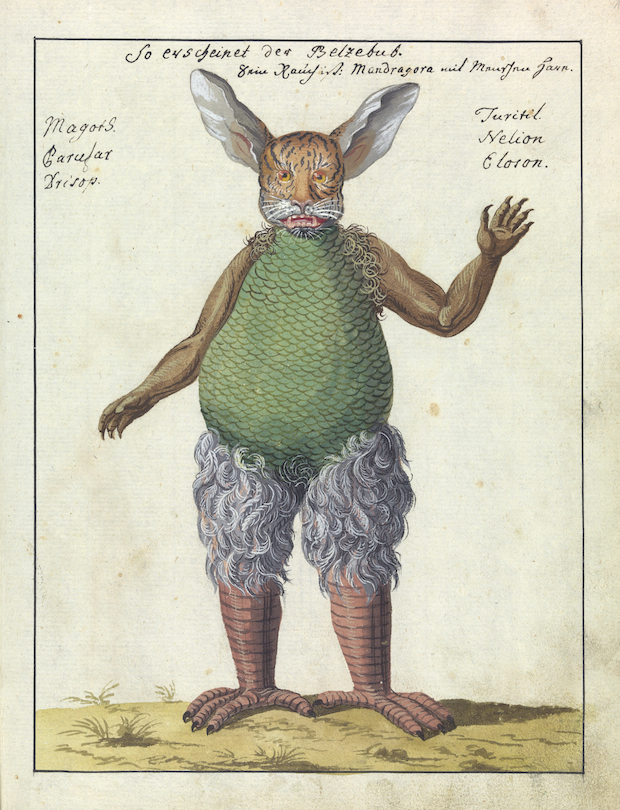

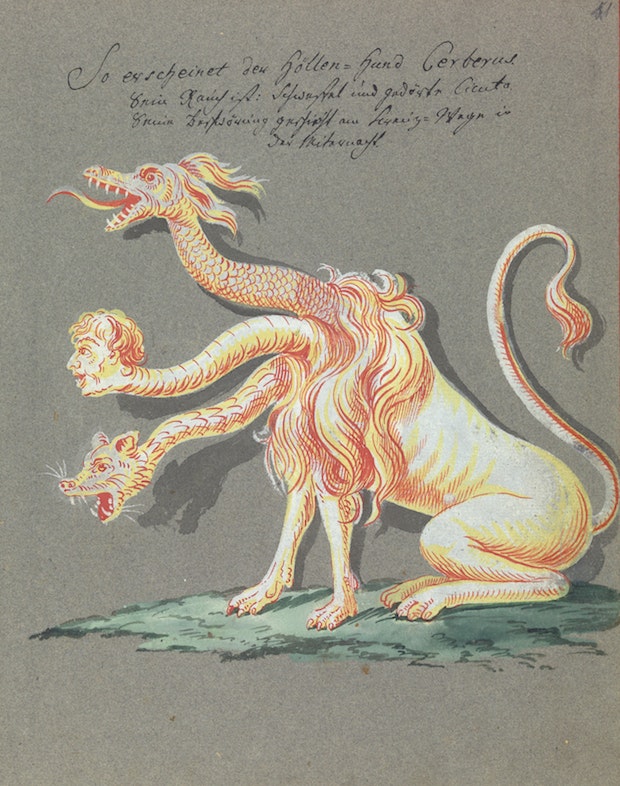

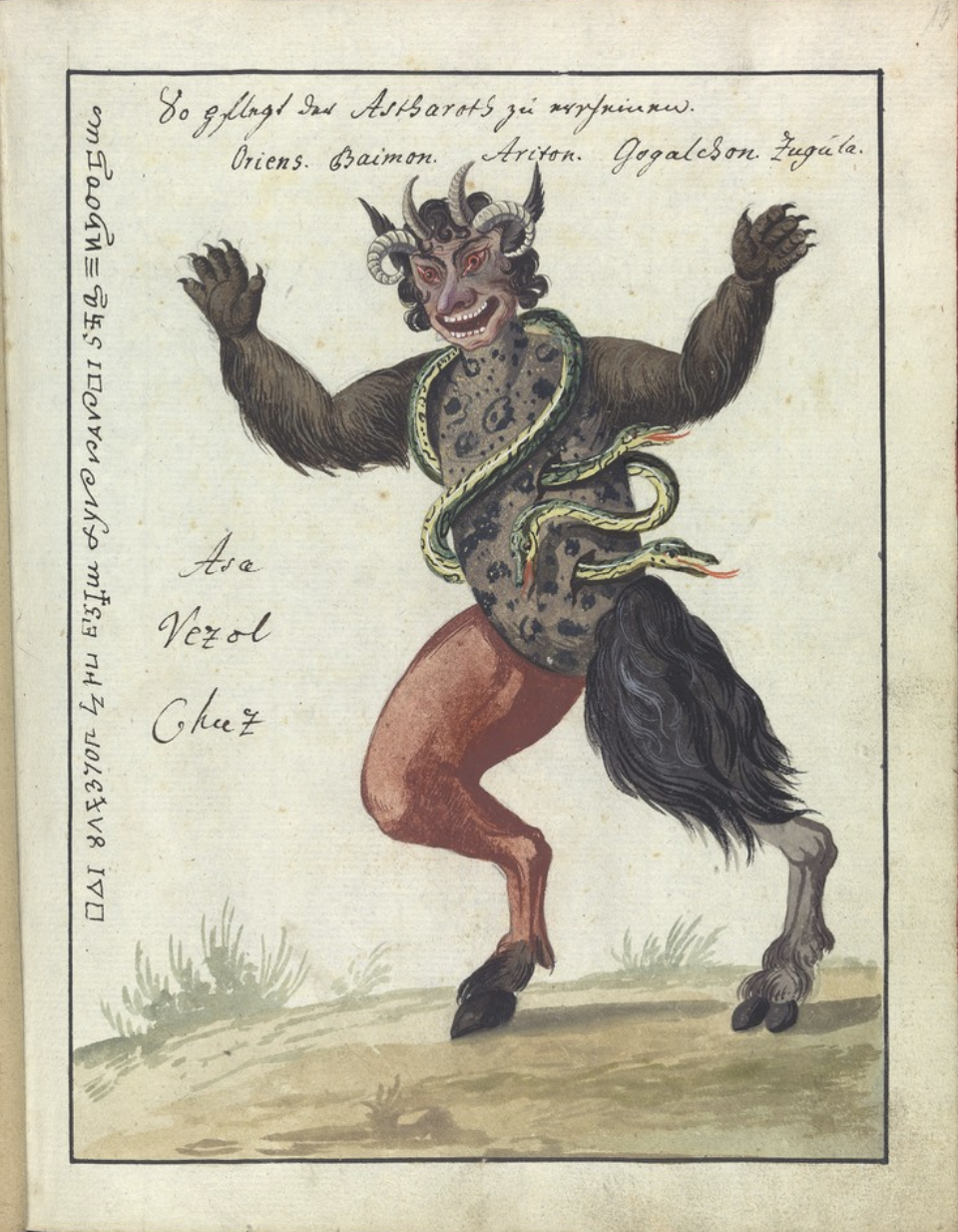

Noli me tangere, says the title page of the Compendium of Demonology and Magic: “Do not touch me.” For the book’s target audience, one suspects, this was more enticement than warning. Written in Latin (its full title is Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae sistematisatae per celeberrimos Artis hujus Magistros) and German, the book purports to come from the year 1057. In fact it’s been dated as more than 700 years younger, though to most 21st-century beholders a book from around 1775 carries enough historical weight to be intriguing — especially if, as the Public Domain Review puts it, it depicts “a varied bestiary of grotesque demonic creatures.”

The specimens catalogued in the Compendium of Demonology and Magic are “up to all sorts of appropriately demonic activities, such as chewing down on severed legs, spitting fire and snakes from genitalia, and parading around decapitated heads on sticks.”

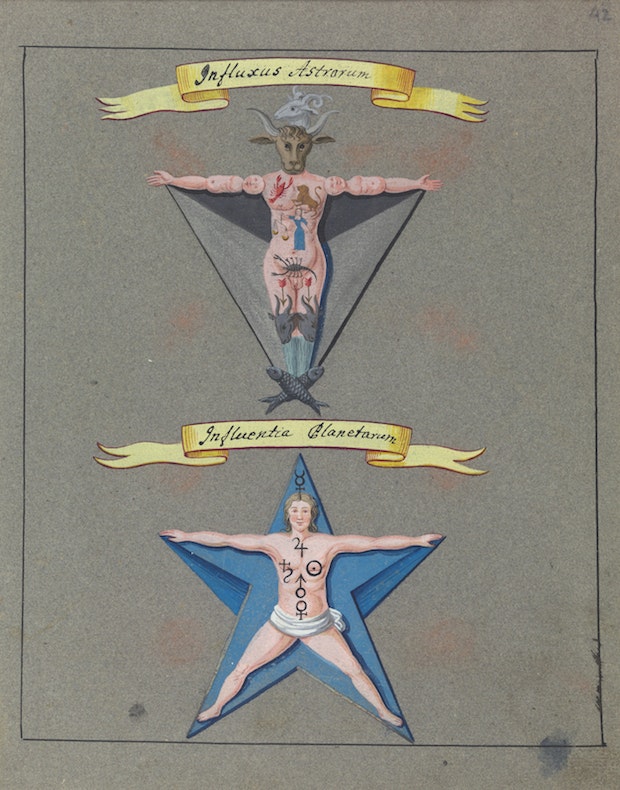

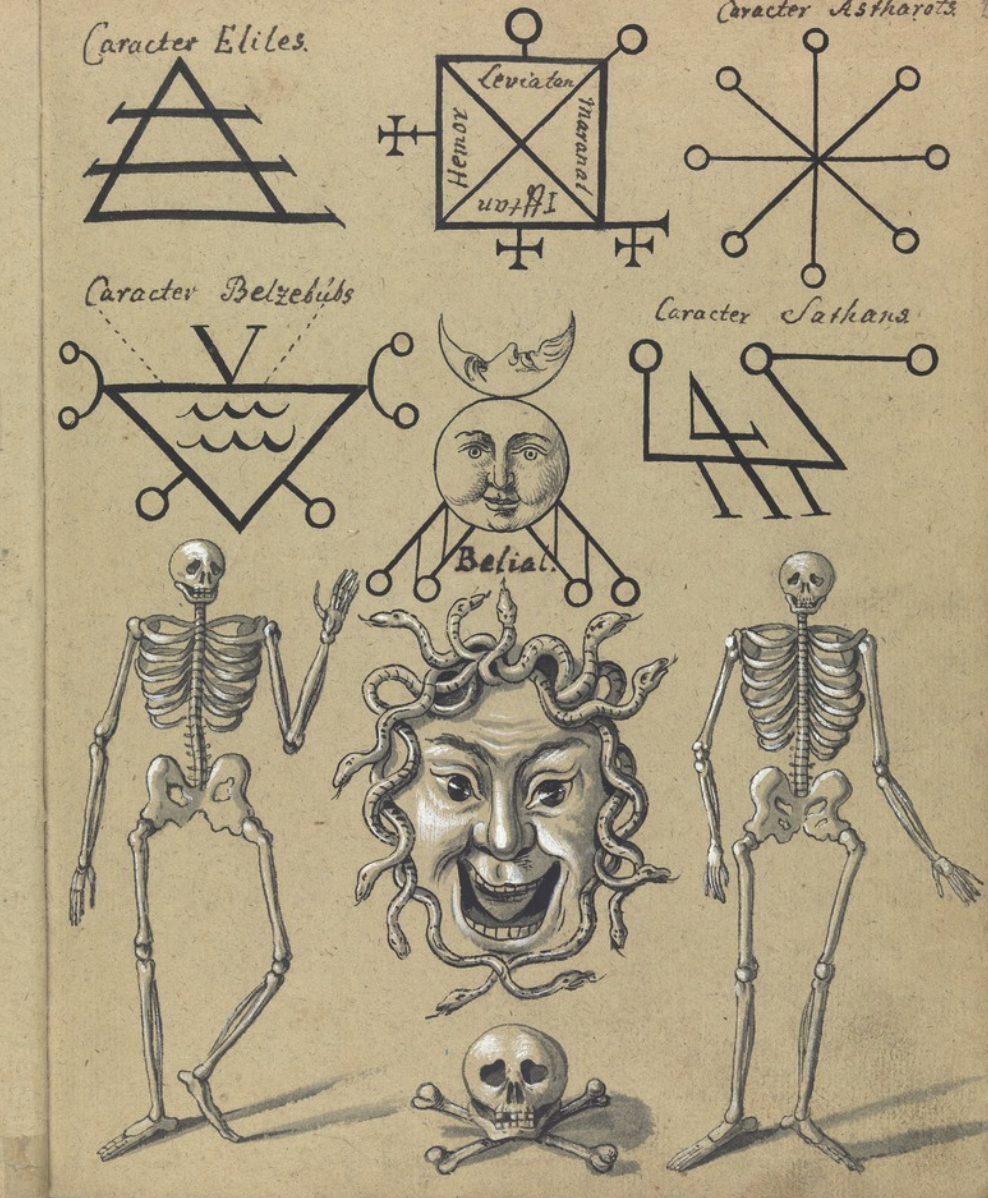

Grotesquely combining features of man and beast, these hideous chimeras are rendered in “more than thirty exquisite watercolors” that still look vivid today. In fact, with their punkish costumes, insouciant expressions, and often indecently exposed nether regions, these demons look ready and willing to cause a scandal even in our jaded time.

Nearly two and a half centuries ago, we might fairly assume, a greater proportion of the public believed in the existence of demons — if not these specific monstrosities, then at least the concept of the demonic in general. But we’re surely lying to ourselves if we believed that nobody in the 16th century had a sense of humor about it. Even the work of this book’s unknown illustrator evidences, beyond formidable artistic skill and wild imagination, a certain comedic instinct, serious business though demonic intentions toward humanity may be.

With its less humorous content including execution scenes and instructions for the procedures of witchcraft from divination to necromancy, the Compendium of Demonology and Magic belongs to a deeper tradition of books that elaborately catalog and depict the varieties of supernatural evil. (A much older example is the Codex Gigas, previously featured here on Open Culture, a “Devil’s Bible” that also happens to be the largest medieval manuscript in the word.)

You can behold more of these delightfully hellish illustrations at the Public Domain Review and even download the whole book free from the Wellcome Collection. (See a PDF of the entire book here.) And no matter how closely you scrutinize your digital copy, you won’t run the risk of touching it.

The Compendium of Demonology and Magic is one of the many texts featured in The Madman’s Library: The Strangest Books, Manuscripts and Other Literary Curiosities from History, a new book featured on our site earlier this week.

Related Content:

The Foot-Licking Demons & Other Strange Things in a 1921 Illustrated Manuscript from Iran

Behold the Codex Gigas (aka “Devil’s Bible”), the Largest Medieval Manuscript in the World

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.