And therefore my opinion is, that when once forty years old we should consider our time of life as an age to which very few arrive; for seeing that men do not usually last so long, it is a sign that we are pretty well advanced; and since we have exceeded the bounds which make the true measure of life, we ought not to expect to go much further. —Michel de Montaigne

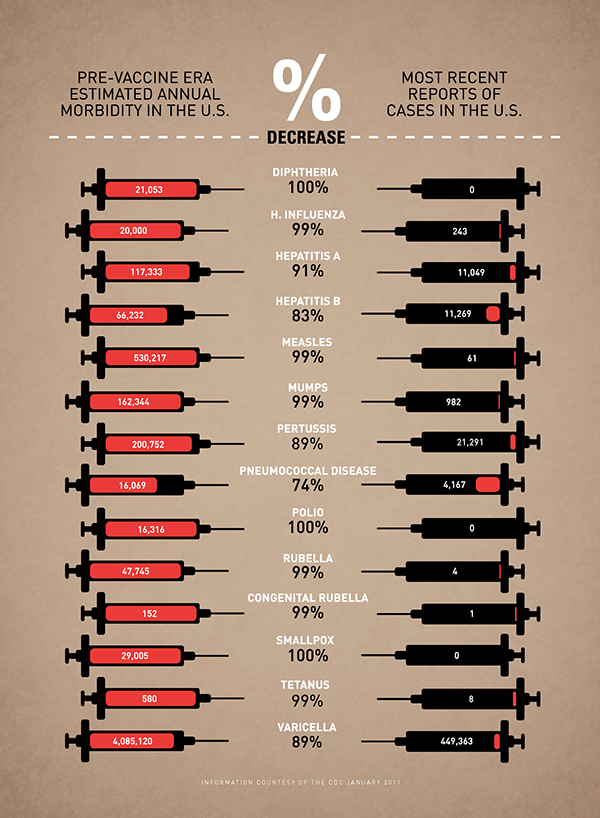

After his retirement at age 38, renaissance essayist Michel de Montaigne devoted several pages to the subject of mortality, as pressing an issue for him as for the classical philosophers he adored. And no less pressing an issue for us, of course. The brute fact of death aside, the quality of our lives has little in common with those of Cato, Seneca, or Montaigne himself. We meet needs and wants with commands to Alexa. We are beset by global anxieties they never imagined, and by remedies that would have saved millions in their time. Even in the age of Covid-19, life isn’t nearly so precarious as it was in 16th century France.

But whether we set the threshold at 40, 80, or 100, “to die of old age is a death rare, extraordinary, and singular,” Montaigne argued. Few attain it today. “It is the last and extremest sort of dying… the boundary of life beyond which we are not to pass, and which the law of nature has pitched for a limit not to be exceeded.” For these reasons and more, we look to the very aged for wisdom: they have attained what most of us will not, and can only look backwards, seeing the fullness of life, if they have clarity, in panoramic hindsight. Such vision is the subject of the 2016 short film above, in which three uniquely lucid centenarians dispense advice, reflect on their experience, and reminisce about the jazz age.

“I have always been lucky,” says now-108-year-old Tereza Harper. “I’ve never been unlucky.” No one lives to such an advanced age without facing a little hardship. Harper immigrated to England from Czechoslovakia during World War II to reunite with her father, who had been a prisoner of war. She lived to witness the many horrors of the 20th century and the many of the 21st so far. And yet, she says, “Everything makes me happy. I love talking to people. I like doing things. I like going out shopping. Once I go out shopping, I don’t really want to come back…. I’m not going yet. I’m still strong. I’m very very strong. I never realized how strong I am.” ”

What is the source of such strength and joy in the ordinary repetitions of daily life? A profound contentment marked by a sense of completion, for one thing. “I don’t think there’s anything that I really need to do,” Harper says, “because I’ve done practically everything that I’ve ever wanted to do in the past.” Likewise, 101-year-old Cliff Crozier, who died last year, remarks, “I think I’ve done all that I wanted to do.” Later, he adds some nuance: “I don’t have many failures,” he says. “If I’m making a cake and it fails it becomes a pudding.” (He also says, “It always pleases me that I can keep robbing the government with my pension.”)

Are there regrets? Naturally. 102-year-old John Denerley, who passed away in 2018, says ruefully, “If I’d have been more attentive at school in my early life, I’d have studied more, and harder…. Well, I didn’t do too bad in the end. But I think the sooner you start studying the better.” Crozier expresses regrets over the way he treated his father, a relationship that still causes him grief. These three are not, after all, superhumans. They are subject to the same pains as the rest of us. But they have achieved a vantage from which to see the whole of life from its limit. Whether or not we achieve the same, we can all learn from them how to make the most of the “extraordinary fortune,” as Montaigne wrote, “which has hitherto kept us above ground.”

Related Content:

Ram Dass (RIP) Offers Wisdom on Confronting Aging and Dying

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness