Photo via Oregon State University

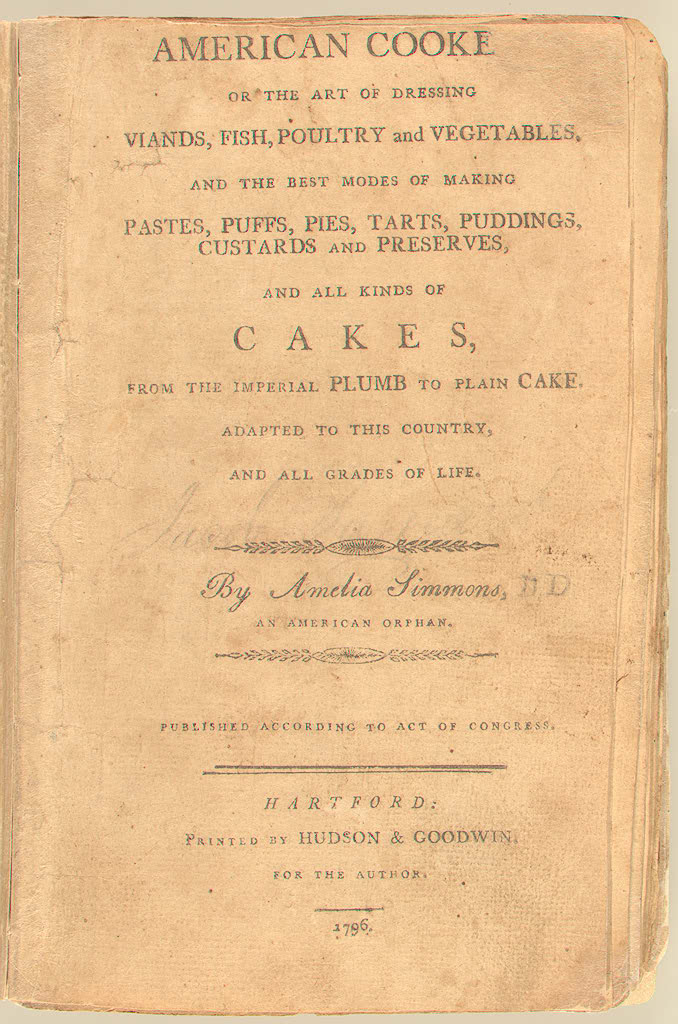

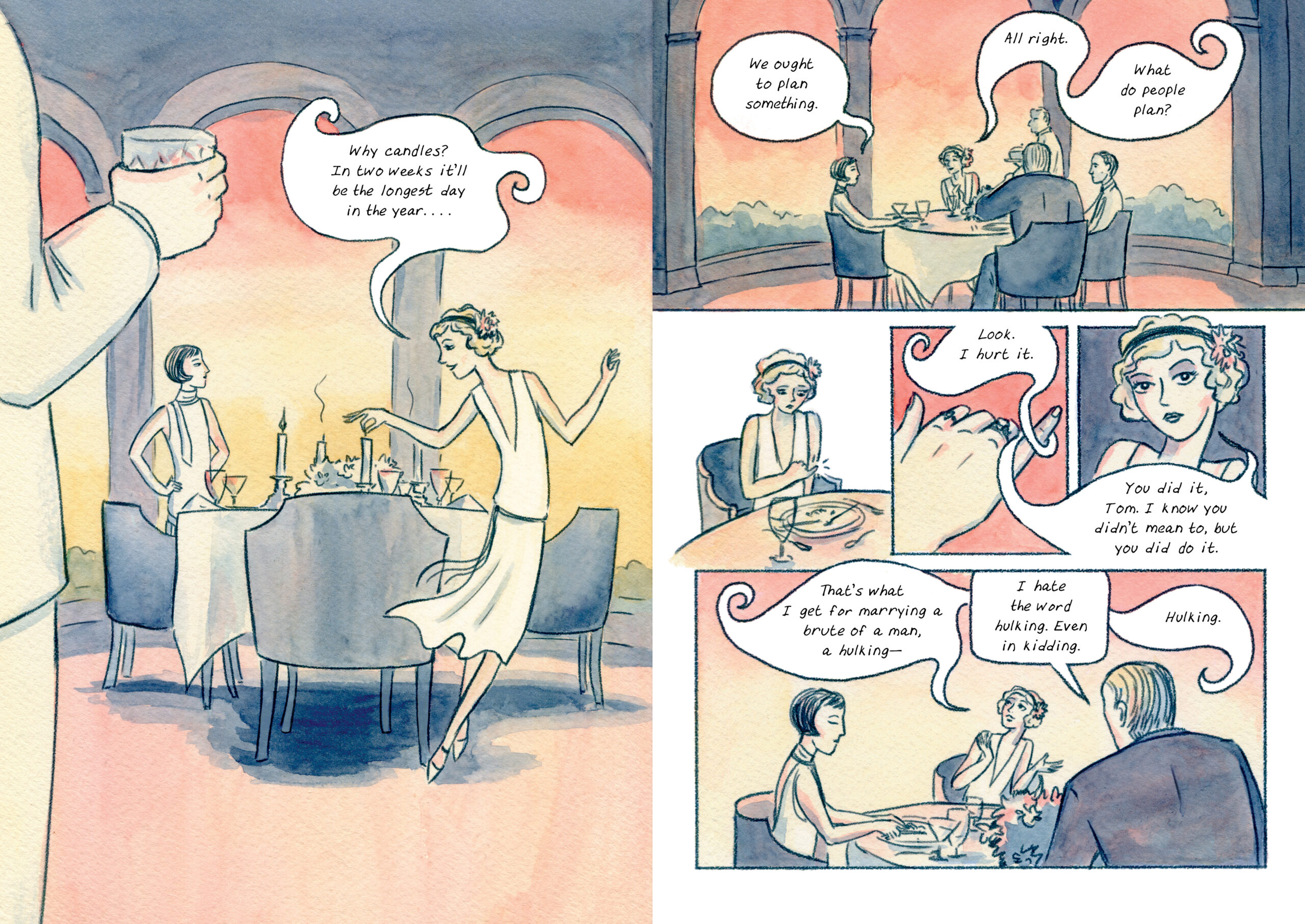

“Color is part of a spectrum, so you can’t discover a color,” says Professor Mas Subramanian, a solid-state chemist at Oregon State University. “You can only discover a material that is a particular color”—or, more precisely, a material that reflects light in such a way that we perceive it as a color. Scientific modesty aside, Subramanian actually has been credited with discovering a color—the first inorganic shade of blue in 200 years.

Named “YInMn blue” —and affectionately called “MasBlue” at Oregon State—the pigment’s unwieldy name derives from its chemical makeup of yttrium, indium, and manganese oxides, which together “absorbed red and green wavelengths and reflected blue wavelengths in such a way that it came off looking a very bright blue,” Gabriel Rosenberg notes at NPR. It is a blue, in fact, never before seen, since it is not a naturally occurring pigment, but one literally cooked in a laboratory, and by accident at that.

The discovery, if we can use the word, should justly be credited to Subramanian’s grad student Andrew E. Smith who, during a 2009 attempt to “manufacture new materials that could be used in electronics,” heated the particular mix of chemicals to over 2000 degrees Fahrenheit. Smith noticed “it had turned a surprising, bright blue color [and] Subramanian knew immediately it was a big deal.” Why? Because the color blue is a big deal.

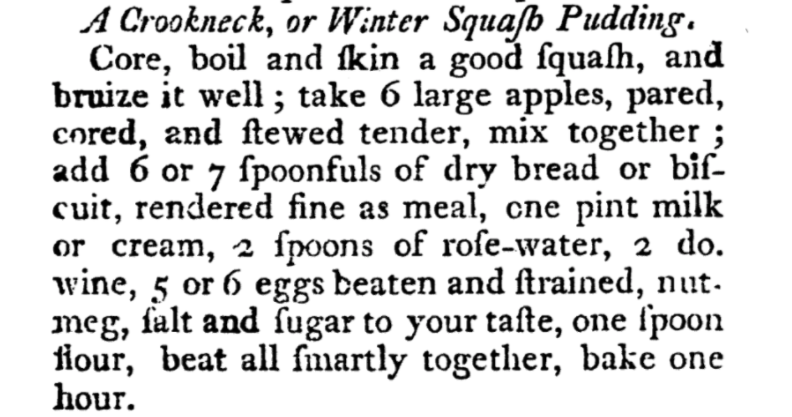

In an important sense, color is something humans discovered over long periods of time in which we learned to see the world in shades and hues our ancestors could not perceive. “Some scientists believe that the earliest humans were actually colorblind,” Emma Taggart writes at My Modern Met, “and could only recognize black, white, red, and only later yellow and green.” Blue, that is to say, didn’t exist for early humans. “With no concept of the color blue,” Taggart writes, “they simply had no words to describe it. This is even reflected in ancient literature, such as Homer’s Odyssey,” with its “wine-dark sea.”

Photo via Oregon State University

Sea and sky only begin to assume their current colors some 6,000 years ago when ancient Egyptians began to produce blue pigment. The first known color to be synthetically produced is thus called Egyptian blue, created using “ground limestone mixed with sand and a copper-containing mineral, such as azurite or malachite.” Blue holds a special place in our color lexicography. It is the last color word that develops across cultures and one of the most difficult colors to manufacture. “People have been looking for a good, durable blue color for a couple of centuries,” Subramanian told NPR.

And so, YInMn blue has become a sensation among industrial manufacturers and artists. Patented in 2012 by OSU, it received approval for industrial use in 2017. That same year, Australian paint supplier Derivan released it as an acrylic paint called “Oregon Blue.” It has taken a few more years for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to come around, but they’ve finally approved YlnMn blue for commercial use, “making it available to all,” Isis Davis-Marks writes at Smithsonian. “Now the authenticated pigment is available for sale in paint retailers like Golden in the US.”

Photo via Oregon State University

The new blue solves a number of problems with other blue pigments. It is nontoxic and not prone to fading, since it “reflects heat and absorbs UV radiation.” YInMn blue is “extremely stable, a property long sought in a blue pigment,” says Subramanian. It also fills “a gap in the range of colors,” says art supply manufacturer Georg Kremer, adding, “The pureness of YInBlue is really perfect.”

Since their first, accidental color discovery, “Subramanian and his team have expanded their research and have made a range of new pigments to include almost every color, from bright oranges to shades of purple, turquoise and green,” notes the Oregon State University Department of Chemistry. None have yet had the impact of the new blue. Learn much more about the unique chemical properties of YInMn blue here and see Professor Subramanian discuss its discovery in his TED talk further up.

Related Content:

Behold One of the Earliest Known Color Charts: The Table of Physiological Colors (1686)

A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete Digital Scan

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness