When I became the Kennedy Center Education Artist-in-Residence, I didn’t realize the most impactful word in that title would be “Residence.” —illustrator Mo Willems

Even as schools regroup and online instruction gathers steam, the scramble continues to keep cooped-up kids engaged and happy.

These COVID-19-prompted online drawing lessons and activities might not hold much appeal for the single-minded sports nut or the junior Feynman who scoffs at the transformative properties of art, but for the art‑y kid, or fans of certain children’s illustrators, these are an excellent diversion.

Mo Willems, author of Knuffle Bunny and the Kennedy Center’s first Education Artist-in-Residence, is opening his home studio every weekday at 1pm EST for approximately twenty minutes worth of LUNCHDOODLES. Episode 5, finds him using a fat marker to doodle a Candyland-ish game board (sans treacle).

Once the design is complete, he rolls the dice to advance both his piece and that of his home viewer. A 5 lands him on the crowd-pleasing directive “fart.” Clearly the online instructor enjoys certain liberties the classroom teacher would be ill-advised to attempt.

Check out the full playlist on the Kennedy Center’s YouTube channel and download activity pages for each episode here.

#MoLunchDoodles

If the daily LUNCHDOODLES leaves ‘em wanting more, there’s just enough time for a quick pee and snack break before Lunch Lady’s Jarrett J. Krosoczka takes over with Draw Everyday with JJK, a basic illustration lesson every weekday at 2pm EST. These are a bit more nitty gritty, as JJK, the kid who loved to draw and grew up to be an artist, shares practical tips on penciling, inking, and drawing faces. Pro tip: resistant Star Wars fans will likely be hooked by the first episode’s Yoda, a character Krosoczka is well versed in as the author and illustrator of the Star Wars Jedi Academy series.

Find the complete playlist here.

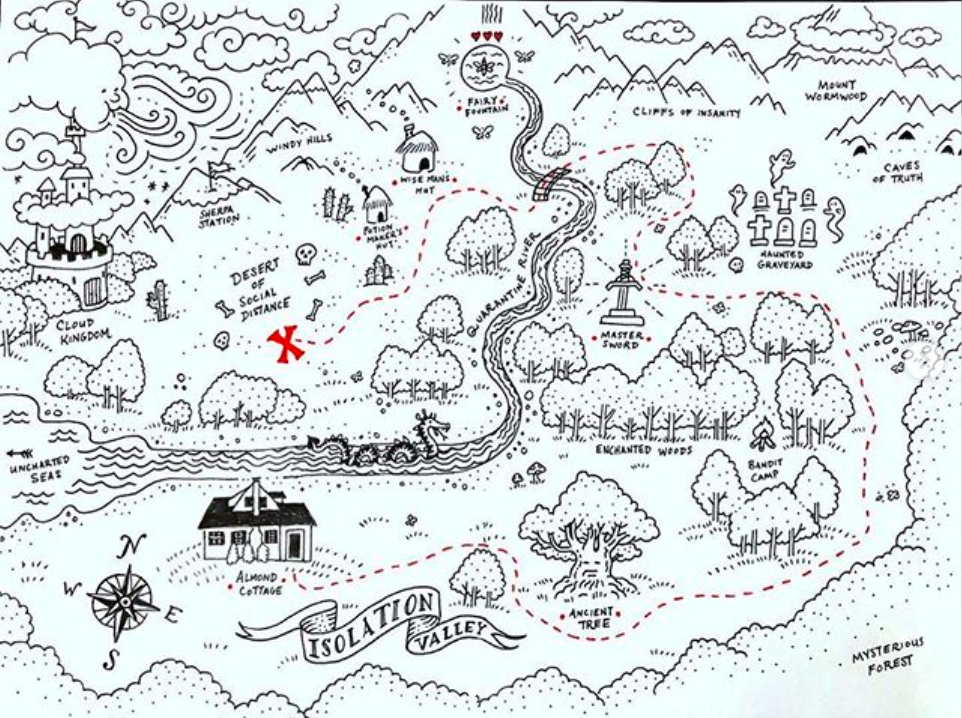

Illustrator Carson Ellis eschews video lessons to host a Quarantine Art Club on her Instagram page. Her most recent assignment is cartography based challenge, with helpful tips for creating an “impactful page turn” for those who wish to share their creations on Instagram:

DRAW A MAP: When we think of treasure maps, we think of sea monsters, islands with palm trees, pirate ships, anthropomorphic clouds blowing gales upon white-capped seas. YOUR map can be of anywhere: an enchanted wood, a dystopian suburb, your backyard, your apartment that has never felt so small, all of the above, none of the above. Or your map can be a traditional treasure map leading to a pirate’s hoard. It’s totally up to you. Three things that you MUST include are: a compass rose (very important—look this up if you don’t know what it is), the name of the place you are mapping, and a red X.

DRAW THE TREASURE: The first part of this assignment is to draw a map with a red X to mark the location of hidden treasure. The second part of this assignment is to draw the treasure. I don’t know what the treasure is. Only you know what the treasure is. Draw it on a separate piece of paper from the map.

BONUS POINTS: If you’re going to post this on instagram, I recommend formatting it with two images. Post the map first, then the treasure which the viewer will swipe to see. This will create what we in the kids book world call AN IMPACTFUL PAGE TURN. That’s the thing that happens when you’re reading a picture book and you turn the page to discover something funny or surprising. It’s kind of hard to explain, but you know a good page turn when you’ve experienced one.

#QuarantineArtClub

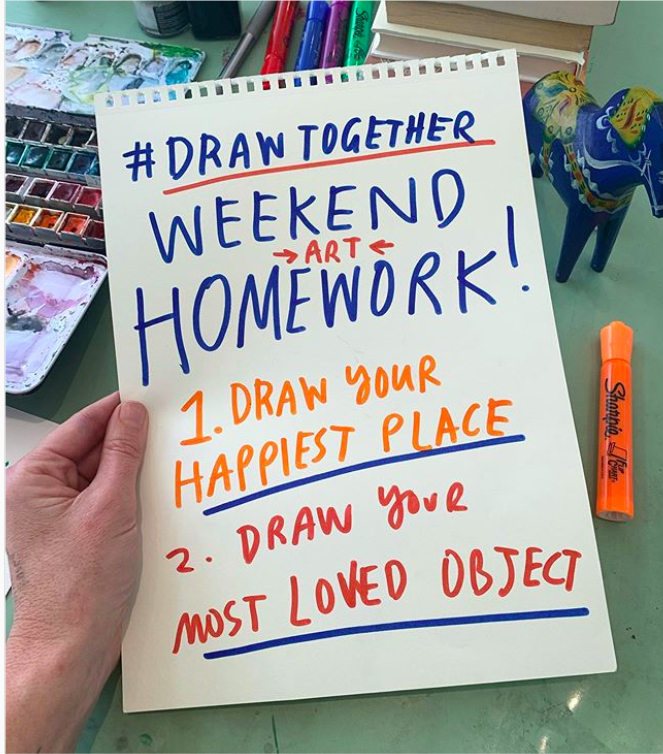

Wendy McNaughton, who specializes in drawn journalism, also likes the Instagram platform, hosting a live Draw Together session every school day, from 10–10.30 am PST. Her approach is a bit more freeform, with impromptu dance parties, special guests, and field trips to the backyard.

Her How to Watch Draw Together highlight is a hilarious crash course in Instagram Live, scrawled in magic marker by someone who’s possibly only now just getting a grip on the platform. Don’t see it? Maybe it’s the weekend, or “maybe ask a millennial for help?”

And bless E.B. Goodale, an illustrator, first time author and mother of a young son, who having counteracted the heartbreak of a cancelled book tour with a hastily launched week of daily Instagram Live Toddler Drawing Club meetings, made the decision to scale back to just Tuesdays and Thursdays:

It was fun doing it everyday but turned out to be a bit too much to handle given our family’s new schedule. We’re all figuring it out, right? I hope you will continue to join me in our unchartered territory next week as we draw to stay sane. Tune in live to make requests or watch it later and follow along at home.

(Her How to Draw a Cat tutorial, above, was likely intended for in-person bookstore events relating to her just published Under the Lilacs…)

#drawingwithtoddlers

Our personal favorite is Stickies Art School, whose online children’s classes are led not by multi-disciplinary artist Nina Katchadourian, whose Facebook page serves as the online institution’s home, but rather her senior tuxedo cat, Stickies.

Stickies, who comes to the gig with an impressive command of English, honed no doubt by frequent appearances on Katchadourian’s Instagram page, affects a diffident air to dole out assignments, the latest of which is above.

He allows his students ample time to complete their tasks—thus far all portraits of himself. The next one, to render Stickies in a costume of the artist’s choice, is due Wednesday by 9am, Berlin time.

Stickies also offers positive feedback on submitted work in delightful follow up videos, a responsibility that Katchadourian takes seriously:

There have been so many conversations at NYU Gallatin where I’m on the faculty about online teaching, how to do it, how to think of a studio course in this new form, etc, and I think perhaps that crossed over with the desire to cheer up some people with kids, many of whom are already Stickies fans, or so I have been told.

His child proteges are no doubt unaware that Stickies looked ready to leave the planet several weeks ago, a fact whose import will resonate with many pet owners in these dark days:

Maybe a third element was just being so glad he is still around, that having him actively “out there” feels good and life-affirming at the moment.

Stickies Art School is marvelous fun for adults to audit from afar, via Katchadourian’s public Facebook posts. If you are a parent whose child would like to participate, send her a friend request and mention that you’re doing so on behalf of your child artist.

Searching on the hashtag #artteachersofinstagram will yield many more resources.

Art of Education University has singled out 12 accounts to get you started, as well as lots of helpful information for classroom art teachers who are figuring out how to teach effectively online.

Related Content:

Learn to Draw Butts with Just Five Simple Lines

Cartoonist Lynda Barry Teaches You How to Draw

How to Draw the Human Face & Head: A Free 3‑Hour Tutorial

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Given the cancellation of everything, she’s taken to Instagram to document her social distance strolls through New York City’s Central Park, using the hashtag #queenoftheapeswalk Follow her @AyunHalliday.