Watchers of Westworld will have heard a character in the most recent episode utter the line, “for the first time, history has an author.” It’s as loaded a bit of dialogue as the series has dropped on fans, not least for its suggestion that in the absence of a god we should be better off with an all-knowing machine.

The line might bend the ear of literary scholars for another reason. The idea of authorship is a complicated one. In one sense, maybe, everyone is an author of history, and in another, perhaps no one is. But it’s difficult to comprehend these abstractions—we crave stories with strong characters, hence our veneration of Great Men and Women of the past.

Still, in many times and places, individual authorship was irrelevant. Renaissance thinkers revalued the author as an auctoritas, a worthy figure of influence and renown. “Death of the author” theorists pointed out that the appearance of a literary text could never be reduced to a single, unchanging personality. In religious studies, questions of authorship open onto minefield after minefield. There may be no commonly agreed-upon way to think about what an author is.

Does it make sense, then, to talk about the “world’s first author”? Perhaps. In the TED-Ed lesson above by Soraya Field Fiorio, we learn that the first known person to use written language for literary purposes was named was Enheduanna, a powerful Mesopotamian high priestess who wrote forty-two hymns and three epic poems in cuneiform 4,3000 hundred years ago.

Daughter of Sargon of Akkad, who placed her in a position to rule, Enheduanna lived about “1,500 years before Homer and about 500 years before the Biblical patriarch Abraham.” (There’s considerable doubt, of course, about whether either of those people existed, whether they wrote the works attributed to them, or whether such works were penned by committee, so to speak.)

Sargon was also an author, having composed an autobiography, The Legend of Sargon, that “exerted a powerful influence over the Sumerians he sought to conquer,” notes Joshua J. Mark at the Ancient History Encyclopedia. But first, Enheduanna used her position as high priestess to unify her father’s empire with religious hymns that praised the gods of each major Sumerian city. “In her writing, she humanized the once aloof gods,” just as Homer would hundreds of years later. “Now they suffered, fought, loved, and responded to human pleading.”

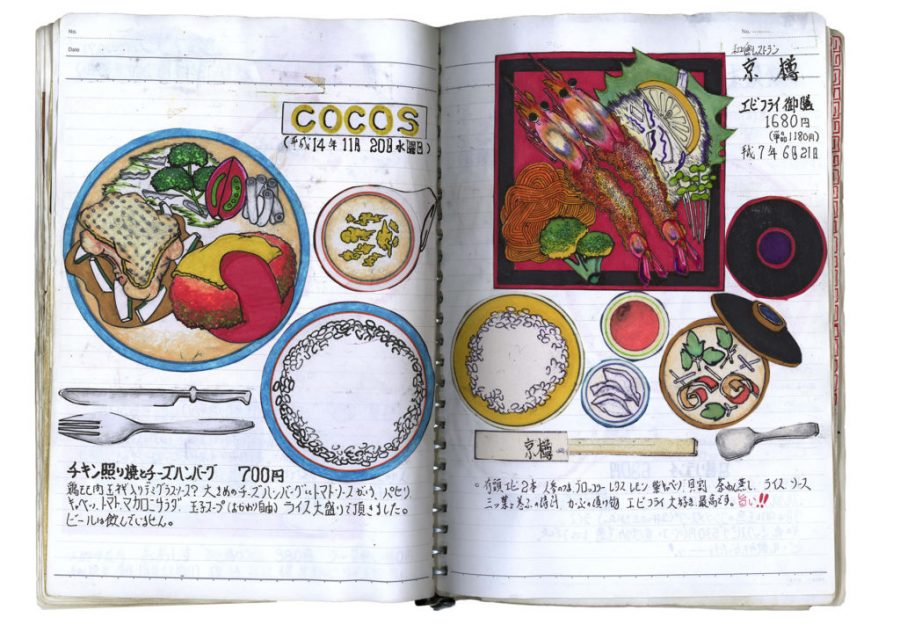

Her hymns to Inanna are her most defining literary achievement, but Enheduanna has somehow been completely left out of history. “We know who the first novelist is,” writes Charles Halton at Lit Hub, “eleventh century Japanese Noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, who wrote the Tale of Genji.” Likewise, we know the first novelist of the western world, Miguel de Cervantes, and the first essayist, Michel de Montaigne. But “ask any person in your life who wrote the first poem and they’re apt to draw a blank.”

Maybe this is because, unlike novels, we don’t think of poetry as being invented by a single individual. It seems as though it must have sprung from the collective psyche not long after humans began using language. Yet from the point of view of literary history—which, like most histories, consists of a succession of great names—Enheduanna certainly deserves the honor as the world’s first known poet and first known author. Learn more about her in the lesson above.

Related Content:

How to Write in Cuneiform, the Oldest Writing System in the World: A Short, Charming Introduction

Watch a 4000-Year Old Babylonian Recipe for Stew, Found on a Cuneiform Tablet, Get Cooked by Researchers from Yale & Harvard

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in its Original Ancient Language, Akkadian

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness