After her analysis of totalitarianism in Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union, Hannah Arendt turned her scholarly attention to the subject of revolution—namely, to the French and American Revolutions. However, the first chapter of her 1963 book On Revolution opens with a paraphrase of Lenin about her own time: “Wars and revolutions… have thus far determined the physiognomy of the twentieth century.”

Arendt wrote the book on the threshold of many wars and revolutions yet to come, but she was not particularly sympathetic to the leftist turn of the 1960s. On Revolution favors the American Colonists over the French Sans Culottes and Jacobins. The book is in part an intellectual contribution to anti-Communism, one of many ideologies, Arendt writes, that “have lost contact with the major realities of our world”?

What are those realities? “War and revolution,” she argues, “have outlived all their ideological justifications… no cause is left but the most ancient of all, the one, in fact, that from the beginning of our history has determined the very existence of politics, the cause of freedom versus tyranny.” This sounds like pamphleteering, but Arendt did not use such abstractions lightly. As one of the foremost scholars of ancient Greek and modern European philosophy, she was eminently qualified to define her terms.

Her students, on the other hand, might have struggled with such weighty concepts as “revolution,” “rights, “freedom,” etc. which can so easily become meaningless slogans without substantive elaboration and “contact with reality.” Arendt was a thorough teacher. Once her students left her class, they surely had a better grasp on the intellectual history of liberal democracy. Such understanding constituted Arendt’s life’s work, and it was through teaching that she developed and refined the ideas that became On Revolution.

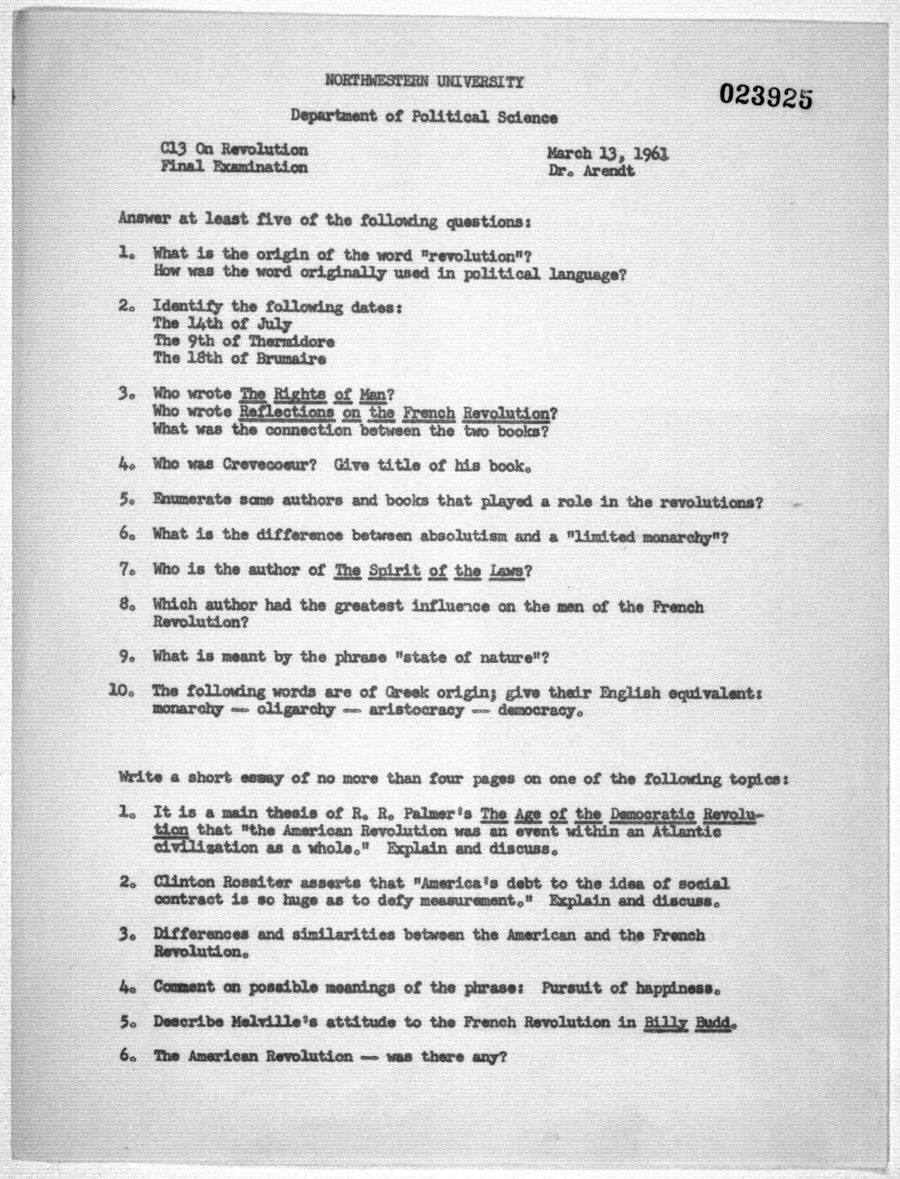

Arendt began research for the book at Princeton, where she was appointed the first woman to serve as a full professor in 1953. Throughout the 50s and early 60s, she taught at Berkeley, Columbia, Cornell, the University of Chicago, and Northwestern before joining the faculty of the New School. In 1961, she taught a Northwestern seminar called “On Revolution.” Just above, you can see the course’s final exam. (View it in a larger format here.) If you’re wondering why she gave the test in March, perhaps it’s because the following month, she boarded a plane to cover the Adolf Eichmann trial for The New Yorker.

What did Arendt want to make sure that her students understood before she left? See a transcription of the exam questions below. We see the two poles of her later argument coming into focus, the French and the American Revolutionary ideas. The latter example has been seen by many critical philosophers as hardly revolutionary at all, given that it was primarily waged in the interests of merchants and slave-owning plantation owners. It was, as one historian puts it, “a revolution in favor of government.”

This criticism is likely the basis of Arendt’s final question on the test. But in her erudite argument, the American Revolution is foundational to use of “revolution” as a political term of art. As Arendt writes in a late 60s lecture, re-discovered in 2017, “prior to the two great revolutions at the end of the 18th century and the specific sense it then acquired, the word ‘revolution’ was hardly prominent in the vocabulary of political thought or practice.” Rather, it mainly had astrological significance.

Arendt saw all subsequent world revolutions as partaking of the twinned logics of the 18th century. “Its political usage was metaphorical,” she says, “describing a movement back into some pre-established point, and hence a motion, a swinging back to a pre-ordained order.” Generally, that order has been pre-ordained by the revolutionaries themselves. See if your understanding of revolutionary history is up to Arendt’s pedagogical standards, below, and get a more comprehensive history of revolution from the readings on recent course syllabuses here, here, and here.

Answer at least five of the following questions:

- What is the origin of the word “revolution”?

How was the word originally used in political language?

- Identify the following dates:

The 14th of July

The 9th of Thermidore

The 18th of Brumaire

- Who wrote The Rights of Man?

Who wrote Reflections on the French Revolution?

What was the connection between the two books?

- Who was Crevecoeur? Give title of his book.

- Enumerate some authors and books that played a role in the revolutions?

- What is the difference between absolutism and a “limited monarchy”?

- Who is the author of The Spirit of the Laws?

- Which author had the greatest influence on the men of the French Revolution?

- What is meant by the phrase “state of nature”?

- The following words are of Greek origin; give their English equivalent: monarchy—oligarchy—aristocracy—democracy.

Write a short essay of no more than four pages on one of the following topics:

-

It is a main thesis of R.R. Palmer’s The Age of the Democratic Revolution that “the American Revolution was an event within an Atlantic civilization as a whole.” Explain and discuss.

-

Clinton Rossiter asserts that “America’s debt to the idea of social contract is so huge as to defy measurement.” Explain and discuss.

-

Differences and similarities between the American and the French Revolution.

-

Connect on possible meanings of the phrase: Pursuit of happiness.

-

Describe Melville’s attitude to the French Revolution in Billy Budd.

-

The American Revolution—was there any?

via Samantha Hill

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness