In the early 19th century, Aristotle’s Meteorologica still guided scientific ideas about the climate. The model “sprang from the ancient Greek concept of klima,” as Ian Beacock writes at The Atlantic, a static scheme that “divided the hemispheres into three fixed climatic bands: polar cold, equatorial heat, and a zone of moderation in the middle.” It wasn’t until the 1850s that the study of climate developed into what historian Deborah Cohen describes as “dynamic climatology.”

Indeed, 120 years before Exxon Mobile learned about—and then seemingly covered up—global warming, pioneering researchers discovered the greenhouse gas effect, the tendency for a closed environment like our atmosphere to heat up when carbon dioxide levels rise. The first person on record to link CO2 and global warming, amateur scientist Eunice Newton Foote, presented her research to the Eight Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1856.

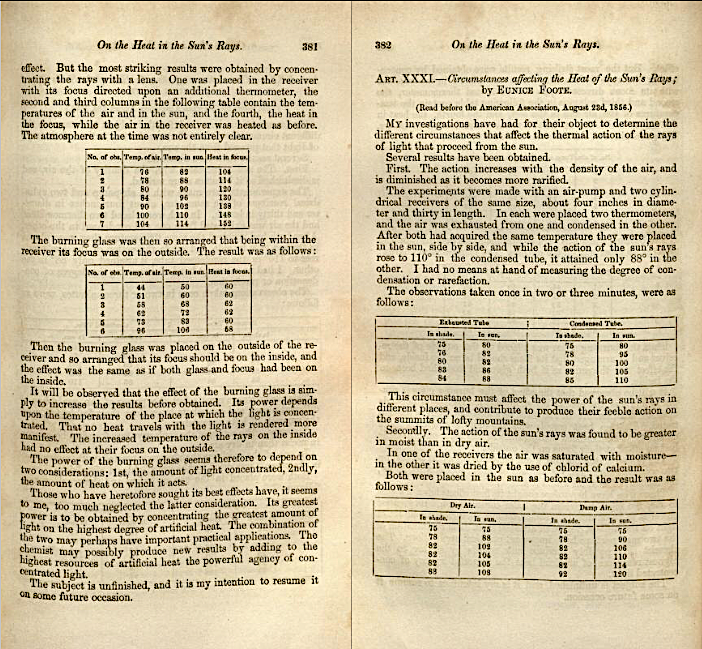

Foote’s paper, “Circumstances affecting the heat of the sun’s rays,” was reviewed the following month in the pages of Scientific American, in a column that approved of her “practical experiments” and noted, “this we are happy to say has been done by a lady.” She used an air pump, glass cylinders, and thermometers to compare the effects of sunlight on “carbonic acid gas” (or carbon dioxide) and “common air.” From her rudimentary but effective demonstrations, she concluded:

An atmosphere of that gas [CO2] would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature…must have necessarily resulted.

Unfortunately, her achievement would disappear three years later when Irish physicist John Tyndall, who likely knew nothing of Foote, made the same discovery. With his superior resources and privileges, Tyndall was able to take his research further. “In retrospect,” one climate science database writes, Tyndall has emerged as the founder of climate science, though the view “hides a complex, and in many ways more interesting story.”

Neither Tyndall nor Foote wrote about the effect of human activity on the contemporary climate. It would take until the 1890s for Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius to predict human-caused warming from industrial CO2 emissions. But subsequent developments depended upon their insights. Foote, whose was born 200 years ago this past July, was marginalized almost from the start. “Entirely because she was a woman,” the Public Domain Review points out, “Foote was barred from reading the paper describing her findings.”

Furthermore, Foote “was passed over for publication in the Association’s annual Proceedings.” Her paper was published in The American Journal of Science, but was mostly remarked upon, as in the Scientific American review, for the marvel of such homespun ingenuity from “a lady.” The review, titled “Scientific Ladies—Experiments with Condensed Gas,” opened with the sentence “Some have not only entertained, but expressed the mean idea, that women do not possess the strength of mind necessary for scientific investigation.”

The praise of Foote credits her as a paragon of her gender, while failing to convey the universal importance of her discovery. At the AAAS conference, the Smithsonian’s Joseph Henry praised Foote by declaring that science was “of no country and of no sex,” a statement that has proven time and again to be untrue in practice. The condescension and discrimination Foote endured points to the multiple ways in which she was excluded as a woman—not only from the scientific establishment but from the educational institutions and funding sources that supported it.

Her disappearance, until recently, from the history of science “plays into the Matilda Effect,” Leila McNeill argues at Smithsonian, “the trend of men getting credit for female scientist’s achievements.” In this case, there’s no reason not to credit both scientists, who made original discoveries independently. But Foote got there first. Had she been given the credit she was due at the time—and the institutional support to match—there’s no telling how far her work would have taken her.

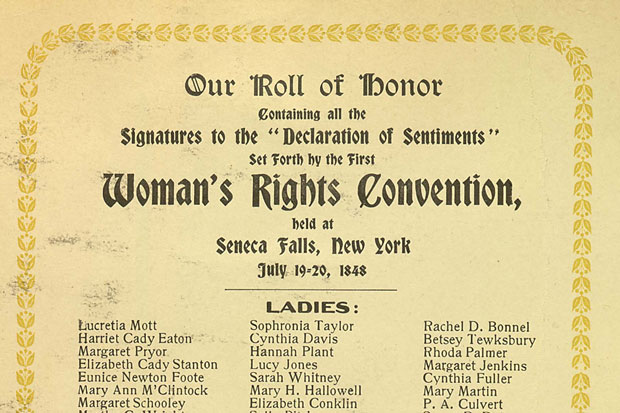

Just as Foote’s discovery places her firmly within climate science history, retrospectively, her “place in the scientific community, or lack therof,” writes Amara Huddleston at Climate.gov, “weaves into the broader story of women’s rights.” Foote attended the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, NY in 1848, and her name is fifth down on the list of signatories to the “Declaration of Sentiments,” a document demanding full equality in social status, legal rights, and educational, economic, and, Foote would have added, scientific opportunities.

Learn much more about Foote and her fascinating family from her descendent, marine biologist Liz Foote.

Related Content:

Women Scientists Launch a Database Featuring the Work of 9,000 Women Working in the Sciences

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness