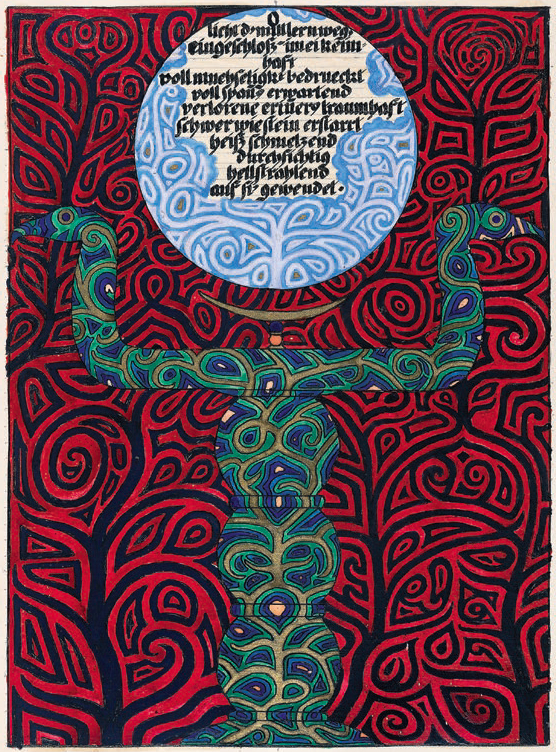

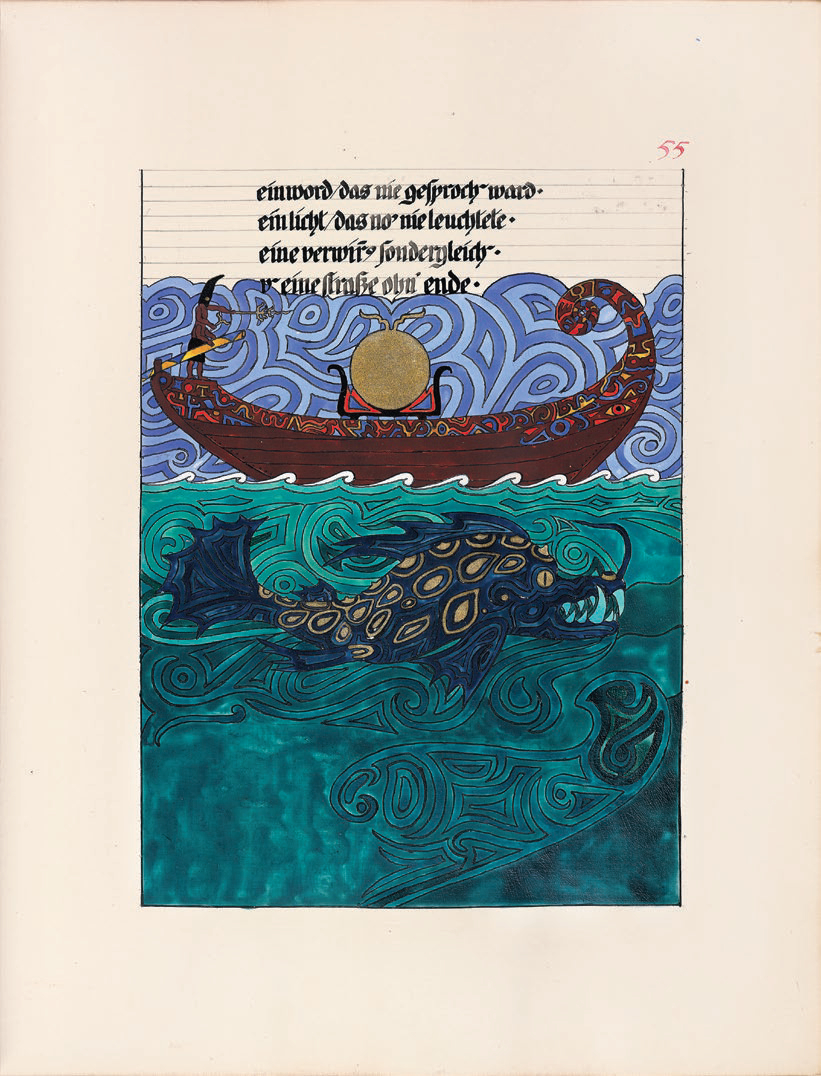

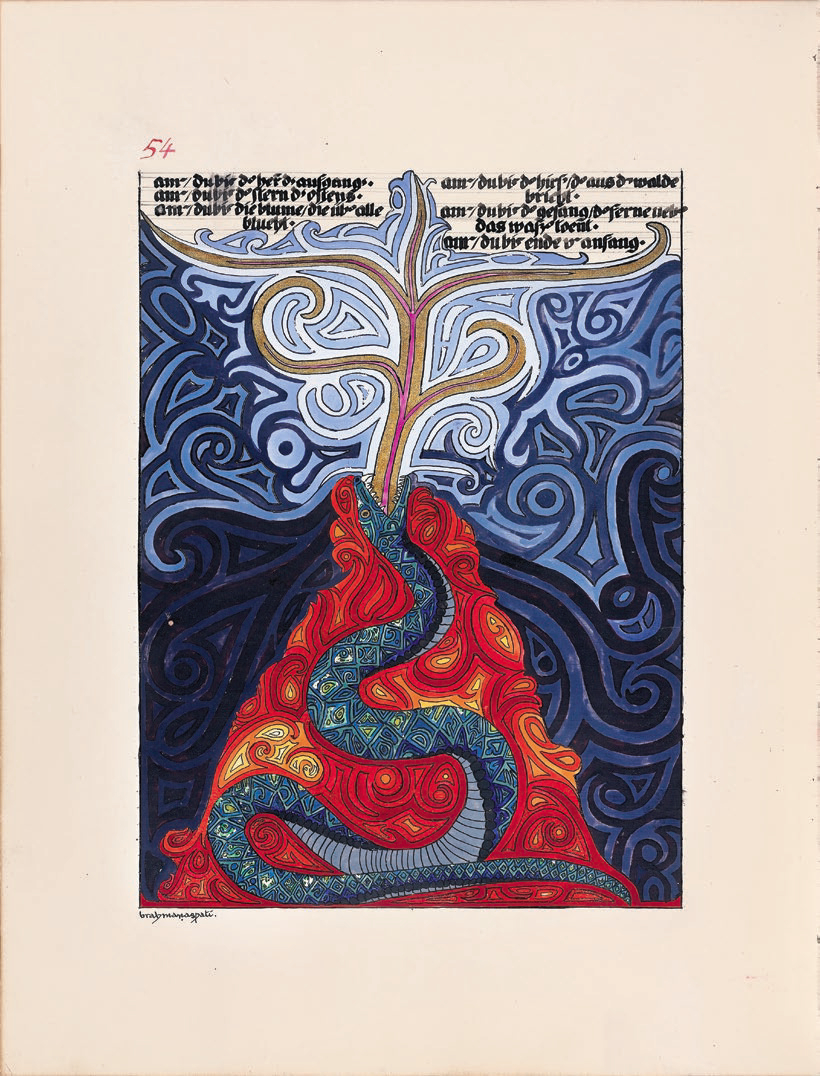

Carl Jung’s Liber Novus, better known as The Red Book, has only recently come to light in a complete English translation, published by Norton in a 2009 facsimile edition and a smaller “reader’s edition” in 2012. The years since have seen several exhibitions of the book, which “could pass for a Bible rendered by a medieval monk,” writes art critic Peter Frank, “especially for the care with which Jung entered his writing as ornate Gothic script.”

Jung “refused to think of himself as an ‘artist’” but “it’s no accident the Liber Novus has been exhibited in museums, or functioned as the nucleus of ‘Encyclopedic Palace,’ the survey of visionary art in the 2013 Venice Biennale.” Jung’s elaborate paintings show him “every bit the artist the medieval monk or Persian courtier was; his art happened to be dedicated not to the glory of God or king, but that of the human race.”

One could more accurately say that Jung’s book was dedicated to the mystical unconscious, a much more nebulous and oceanic category. The “oceanic feeling”—a phrase coined in 1927 by French playwright Romain Rolland to describe mystical oneness—so annoyed Sigmund Freud that he dismissed it as infantile regression.

Freud’s antipathy to mysticism, as we know, did not dissuade Jung, his onetime student and admirer, from diving in and swimming to the deepest depths. The voyage began long before he met his famous mentor. At age 11, Jung later wrote in 1959, “I found that I had been in a mist, not knowing how to differentiate myself from things; I was just one among many things.”

Jung considered his elaborate dream/vision journal—kept from 1913 to 1930, then added to sporadically until 1961—“the central work in his oeuvre,” says Jung scholar Sonu Shamdasani in the Rubin Museum introduction above. “It is literally his most important work.”

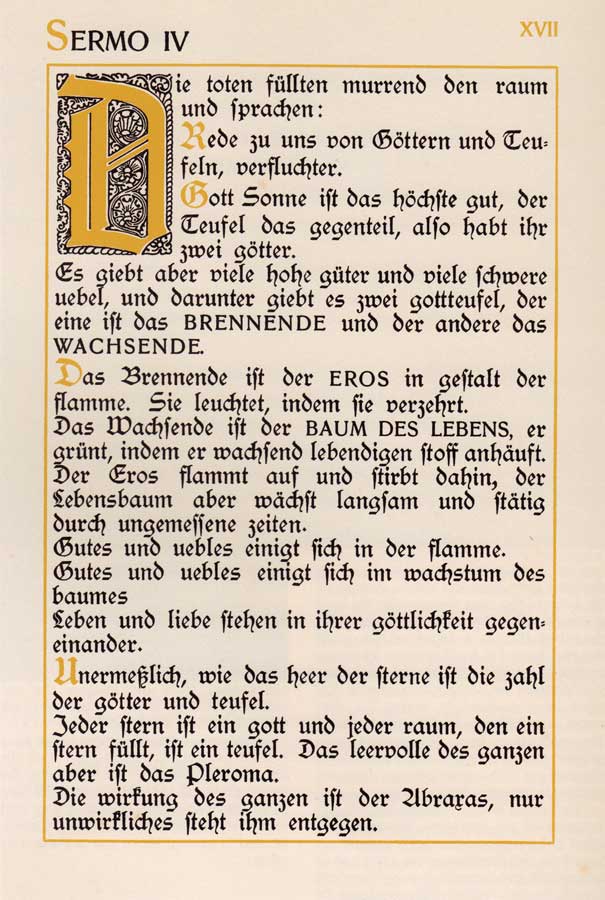

And yet it took Dr. Shamdasani “three years to convince Jung’s family to bring the book out of hiding,” notes NPR. “It took another 13 years to translate it.” Part of the reason his heirs left the book hidden in a Swiss vault for half a century may be evident in the only portion of the Red Book to appear in Jung’s lifetime. “The Seven Sermons of the Dead.”

Jung had this text privately printed in 1916 and gave copies to select friends and family members. He composed it in 1913 in a period of Gnostic studies, during which he entered into visionary trance states, transcribing his visions in notebooks called the “Black Books,” which would later be rewritten in The Red Book.

You can see a page of Jung’s meticulously hand-lettered manuscript above. The “Sermons,” he wrote in a later interpretation, came to him during an actual haunting:

The atmosphere was thick, believe me! Then I knew that something had to happen. The whole house was filled as if there were a crowd present, crammed full of spirits. They were packed deep right up to the door, and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all a‑quiver with the question: “For God’s sake, what in the world is this?” Then they cried out in chorus, “We have come back from Jerusalem where we found not what we sought/’ That is the beginning of the Septem Sermones.

The strange, short “sermons” are difficult to categorize. They are awash in Gnostic theology and occult terms like “pleroma.” The great mystical oneness of oceanic feeling also took on a very sinister aspect in the demigod Abraxas, who “begetteth truth and lying, good and evil, light and darkness, in the same word and in the same act. Wherefore is Abraxas terrible.”

There are tedious, didactic passages, for converts only, but much of Jung’s writing in the “Seven Sermons,” and throughout The Red Book, is filled with strange obscure poetry, complemented by his intense illustrations. Jung “took on the similarly stylized and beautiful manners of non-western word-image conflation,” writes Frank, “including Persian miniature painting and east Asian calligraphy.”

If The Red Book is, as Shamdasani claims, Jung’s most important work—and Jung himself, though he kept it quiet, seemed to think it was—then we may in time come to think of him as not only as an inspirer of eccentric artists, but as an eccentric artist himself, on par with the great illuminators and visionary mystic poet/painters.

Related Content:

The Famous Break Up of Sigmund Freud & Carl Jung Explained in a New Animated Video

Carl Jung Explains His Groundbreaking Theories About Psychology in a Rare Interview (1957)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness