There are many roads to wellness. Meditation, yoga, exercise, and healthy diet are all effective therapies for bringing down stress levels. But we shouldn’t discount an activity we once used to while hours away as children, and that adults by the millions have taken to in recent years. Coloring takes us out of ourselves, say experts like Doctor of Psychiatry Scott M. Bea, “it’s very much like a meditative exercise.” It relaxes our brain by focusing our attention and pushing distracting and disturbing thoughts to the margins. The low stakes make the activity easy and pleasurable, qualities grown-ups don’t get to ascribe to most of what they spend their time doing.

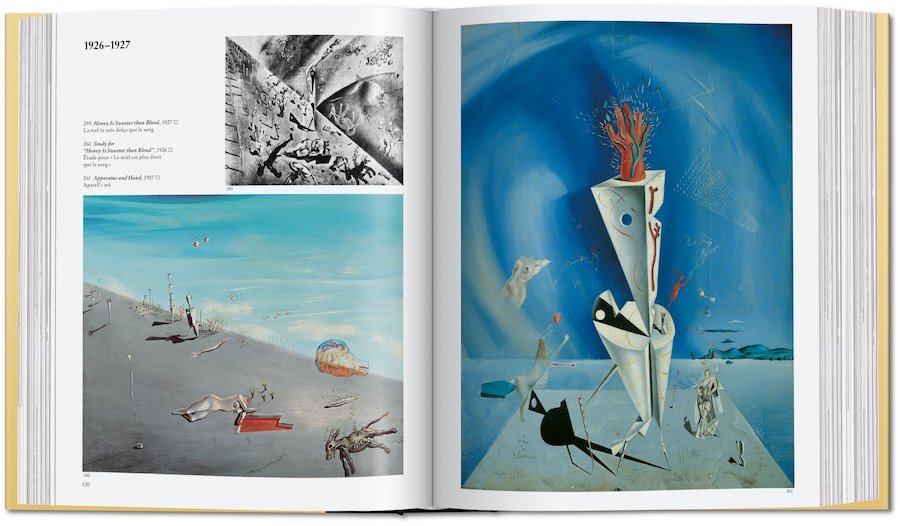

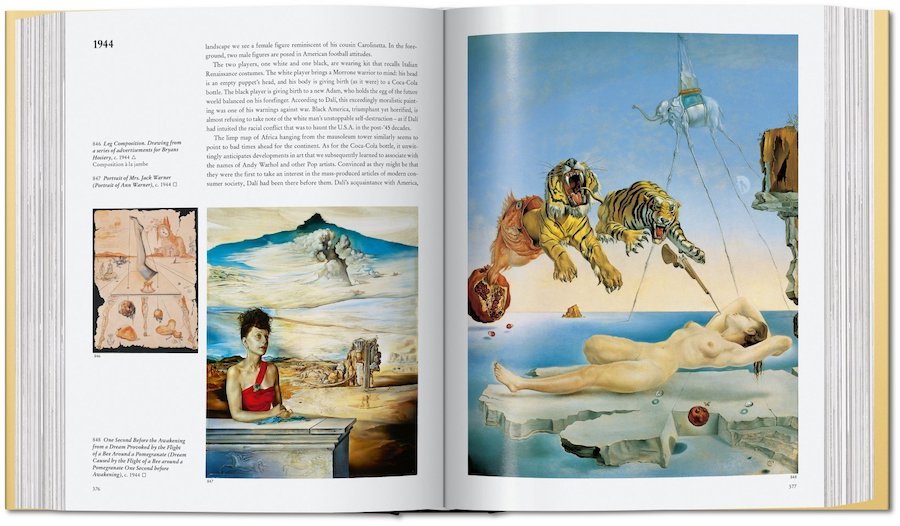

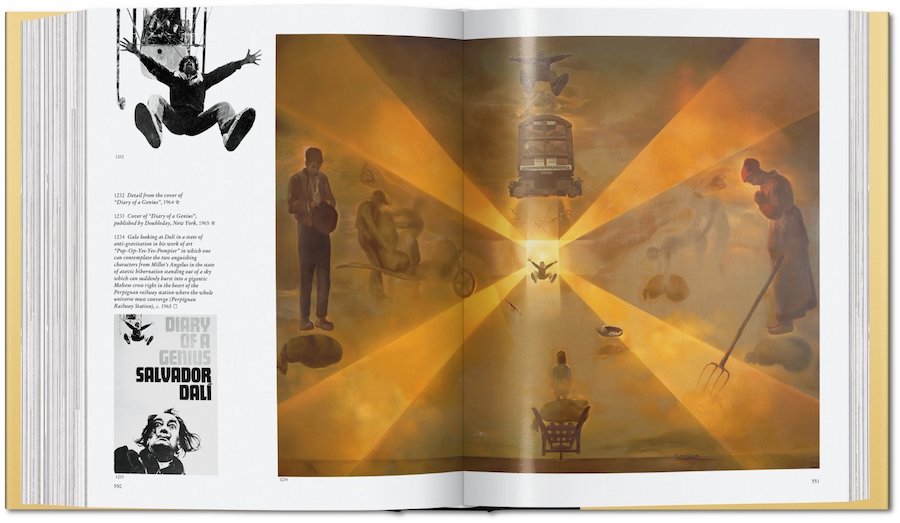

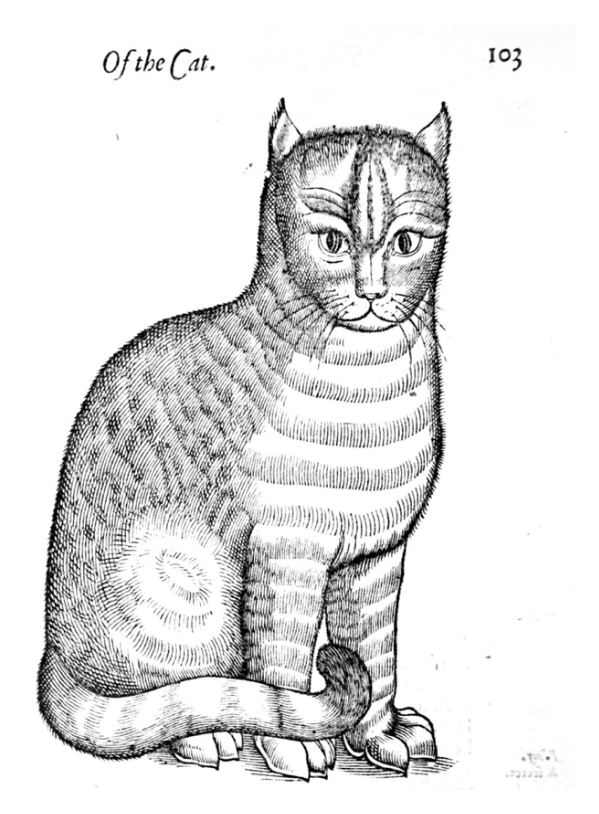

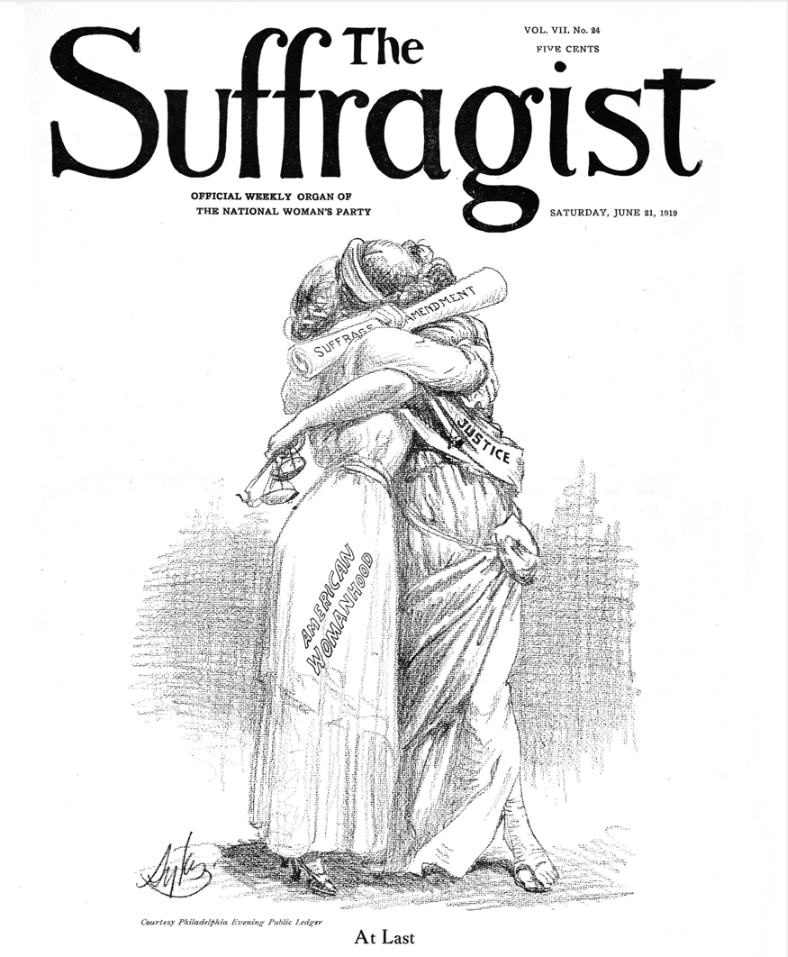

Reducing anxiety is all well and good, but some art and history lovers can’t accept just any old mass-market coloring book. Luckily, a consortium of over a hundred museums and libraries has given these special customers a reason to stick with it. Since 2016, the annual #ColorOurCollections campaign, led by the New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM), has made available, for free, adult coloring books. The range of images offers something for everyone, from early modern illustrations like the cat at the top, from Edward Topsell’s Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes (1607)—courtesy of Trinity Hall Cambridge; to the poignant cover of The Suffragist, below, from July 1919, a month after U.S. women won the right to the vote (from the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens).

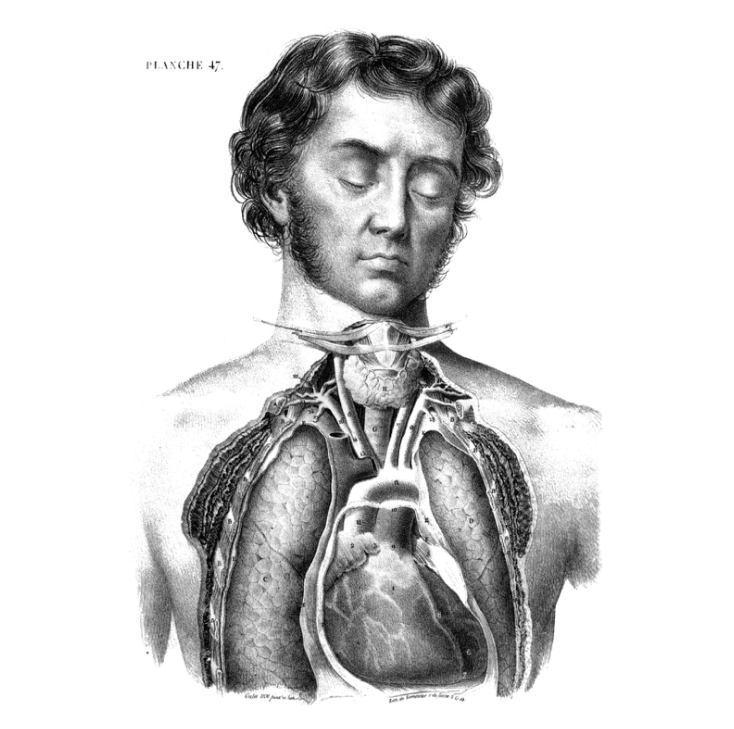

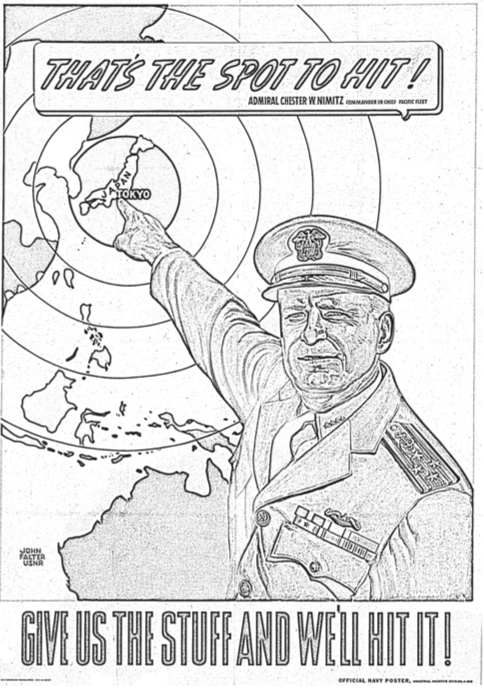

There are, unsurprisingly, copious illustrations of medical procedures and anatomy, like that below from the Library at the University of Barcelona. There are vintage advertisements, “canoe-heavy content” from a Canadian museum, as Katherine Wu reports at Smithsonian, and war posters like that further down of Admiral Chester Nimitz asking for “the stuff” to hit “the spot,” i.e. Tokyo –from the Pritzker Military Museum. “The only commonality shared by the thousands of prints and drawings available on the NYAM website is their black-and-white appearance: The pages otherwise span just about every taste and illustrative predilection a coloring connoisseur could conjure.”

One Twitter fan pointed out that the initiative provides “a great way to get to know some of the collections held in libraries around the world.” Their enthusiasm is catching. But note that few of the institutions (see full collection here) have uploaded a large quantity of colorable images. Most of the “coloring books” consist of only a handful of pages, some only one or two. Taken altogether, however, the combined strength of one hundred institutions, over four years (see previous years at the links below), adds up to many hundreds of pages of coloring fun and relaxation. If that’s your thing, start here. If you don’t know if it’s your thing, #ColorOurCollections is a free (minus the cost of printer ink and paper), educational way to find out. Grab those crayons, oil pastels, colored pencils, etc. and calm down again the way you did when you were six years old.

Related Content:

Download Free Coloring Books from 113 Museums

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness