Among historians of European Christianity, it long seemed a settled question that Irish Catholicism, the so-called “Celtic Rite,” differed significantly in the middle ages from its Roman counterpart. This despite the fact that the phrase Celtic Rite “must not be taken to imply any necessary homogeneity,” notes the Catholic Encyclopedia, “for the evidence such as it is, is in favour of considerable diversity.” Far from an insular religion, Irish Catholicism spread to France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and Northern Spain through the missions of St. Columbanus and others, and both influenced and absorbed the Continent’s practices throughout the medieval period.

Historians have recently set out to “restore [the Irish Church] to its rightful place on the European historical map,” writes Trinity College Dublin’s Ann Buckley in her introduction to a book of scholarly essays called Music, Liturgy, and the Veneration of Saints of the Medieval Irish Church in a European Context.

To varying degrees, all of the scholars represented in this collection write to counter the essentializing “quest for what might be unique or ‘other’ about Ireland and Irish culture” among all other European national and religious histories.

Buckley’s writing on the veneration of Irish saints has made a significant contribution to this effort, and her decade and a half of archival work has helped create the Amra project, which aims “to digitize and make freely available online over 300 manuscripts containing liturgical material associated with some 40 Irish saints which are located in research libraries across Europe.” So write Medievalists.net, who also point out some of the most exciting aspects of this accessible resource:

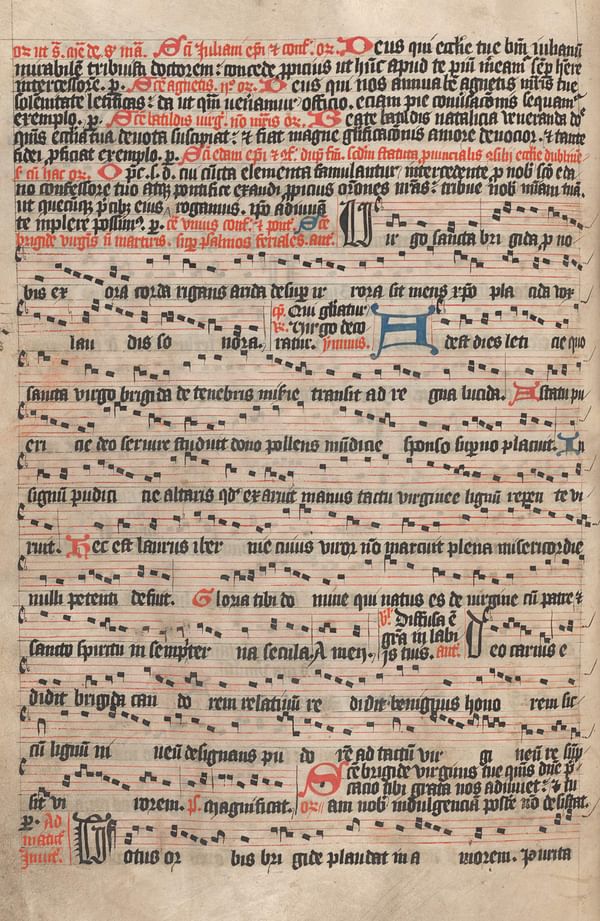

The digital archive, when completed, will also incorporate recordings and performing editions of all the chants and prayers from the original manuscripts, as well as translations of the Latin texts into a number of European languages. In this way, contemporary audiences can enjoy first-hand the devotional songs associated with Irish saints, bringing them out of their slumber after more than half a millennium.

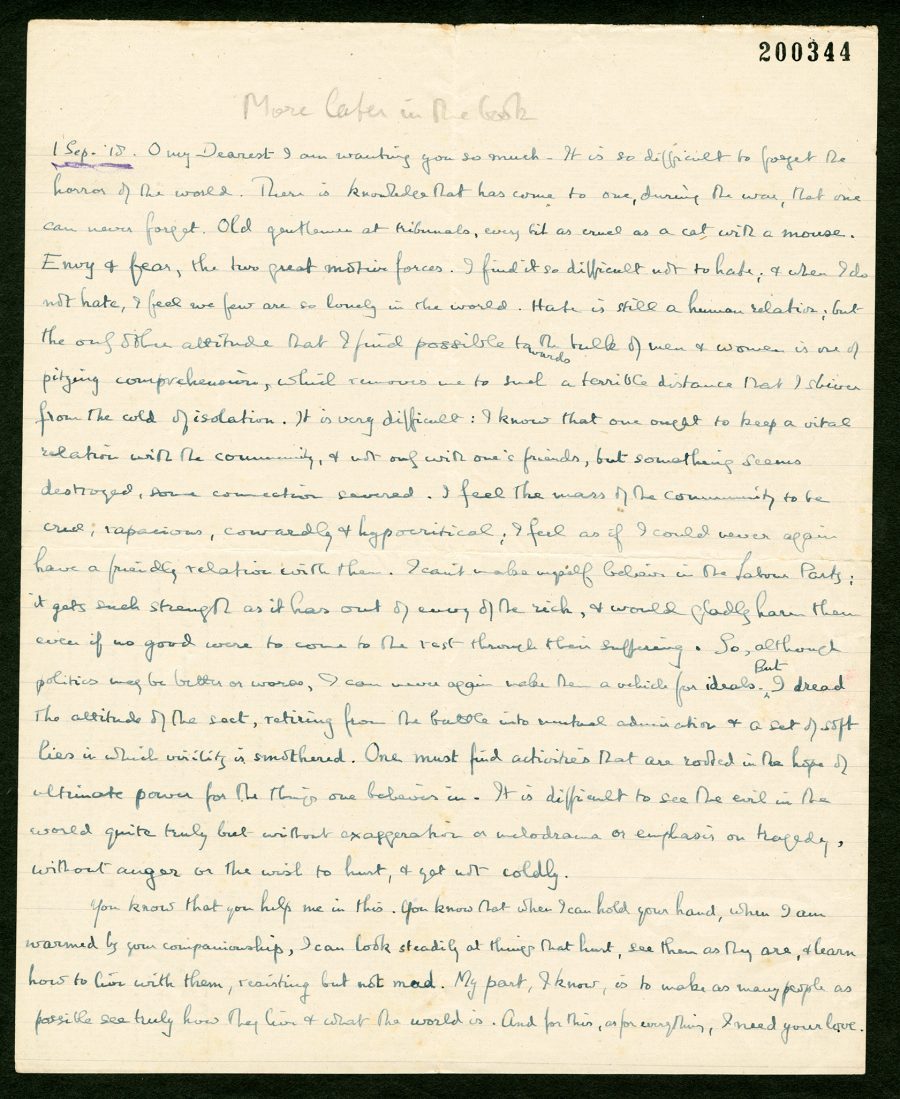

You can hear one antiphonal chant, “Magni patris/Mente mundi,” from the Office St. Patrick, just above. Perhaps unsurprisingly, “no other Irish saint is represented so extensively or with such variety in medieval liturgical sources,” writes Buckley. Manuscript hymns, prayers, and offices for Patrick have been found in Dublin, Oxford, Cambridge, the British Library, and “in the Vienna Schottenkloster dating from the time of its foundation by Irish Benedictine monks in the twelfth century.” (See the opening of the Office of St. Patrick, “Venerenda imminentis,” from a late-15th century manuscript, at the top.)

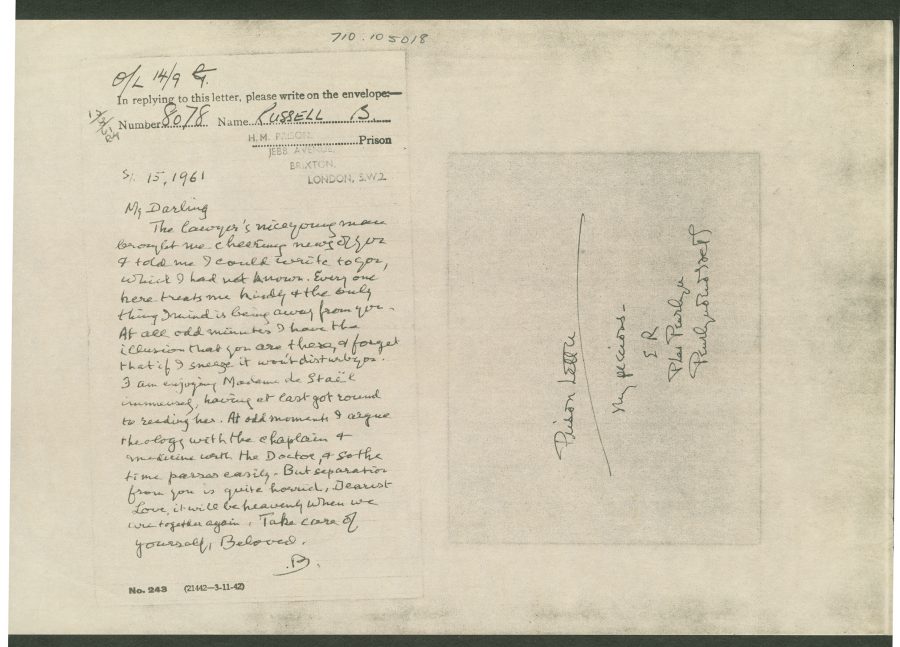

Other saints represented in the archival material include Brigit, Colmcille, Columbanus, Canice, Declan, Ciaran, Finian, and Laurence O’Toole. The missionary monks all received their own “offices,” liturgical ceremonies performed on their feast days. Many of the manuscripts, such as the opening of the Office of St. Brigit, above, contain musical notation, allowing musicologists like Buckley to recreate the sound of Irish Catholicism as it existed in Ireland, Britain, and Continental Europe several hundred years ago.

The project is developing a digital archive of such recordings, as well as “a fully searchable database,” Medievalists.net notes, with “interactive maps showing the geographical distribution of the cults of Irish saints across Europe, and of the libraries where the manuscripts are now housed. A series of documentary films is also envisaged.” You don’t have to be a specialist in the history of the Irish Church, or an Irish Catholic, for that matter, to get excited about the many ways such a rich resource will bring this medieval history to new life.

Related Content:

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized & Put Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness