John Coltrane released “more significant works” than his 1960 “My Favorite Things,” says Robin Washington in a PRX documentary on the classic reworking of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway hit. “A Love Supreme” is often cited as the zenith of the saxophonist’s career. “But if you tried to explain that song to an average listener, you would lose them. [“My Favorite Things”] is a definitive work that everyone knows, and anyone can listen to, and the fascinating story of its evolution is something everyone can share and enjoy.” The song is accessible, a commercially successful hit, and it is also an experimental masterpiece.

Indeed, “My Favorite Things” may be the perfect introduction to Coltrane’s experimentalism. After the dizzying chord changes of 1959’s “Giant Steps,” this 14-minute, two-chord excursion patterned on the ragas of Ravi Shankar announced Coltrane’s move into the modal forms he refined until his death in 1967, as well as his embrace of the soprano saxophone and his new quartet. It became “Coltrane’s most requested tune,” says Ed Wheeler in The World According to John Coltrane, “and a bridge to a broad public audience.”

Coltrane’s take is also mesmerizing, trance-inducing, “often compared to a whirling dervish,” notes the Polyphonic video above, a reference to the Sufi meditation technique of spinning in a circle. It’s an unlikely song choice for the exercise, which makes it all the more fascinating. The Sound of Music, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s final Broadway collaboration, was an “instant classic,” and everyone who’d seen it walked away humming the tune to “My Favorite Things.” By 1960, it had become a standard, with several cover versions released by Leslie Uggams, The Pete King Chorale, the Hi-Lo’s, and the Norman Luboff Choir.

Hundreds more covers would follow. None of them sounded like Coltrane’s. The modal form—in which musicians improvise in different kinds of scales over simplified chord structures—created the “open freedom” in music explored on Miles Davis’ pathbreaking Kind of Blue, on which Coltrane played tenor sax. (It was Davis who bought Coltrane his first soprano sax that year.) Coltrane’s use of modal form in adaptations of popular standards like “My Favorite Things” and George Gershwin’s “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess was an explicit strategy to court a wider public, using the familiar to orient his listeners to the new.

The video essay brings in the expertise of musician, composer, and YouTuber Adam Neely, who explains what makes Rogers and Hammerstein’s classic unique among show tunes, and why it appealed to Coltrane as the centerpiece of the 1961 album of the same name. The song’s unusual form and structure allow the same melody to be played over both major and minor chords. Coltrane’s modification of the song reduces it to the two tonics, E major and E minor, over which he and the band solo, introducing a shifting tonality and mood to the melody with each chord change.

Neely goes into greater depth, but it’s overall an accessible explanation of Coltrane’s very accessible, yet vertiginously deep, “My Favorite Things.” Maybe only one question remains. Coltrane’s rendition came out four years before Julie Andrews’ iconic performance in the film adaptation of The Sound of Music, evoking the obvious question,” says Washington: “Did he influence her?”

Related Content:

Jazz Deconstructed: What Makes John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” So Groundbreaking and Radical?

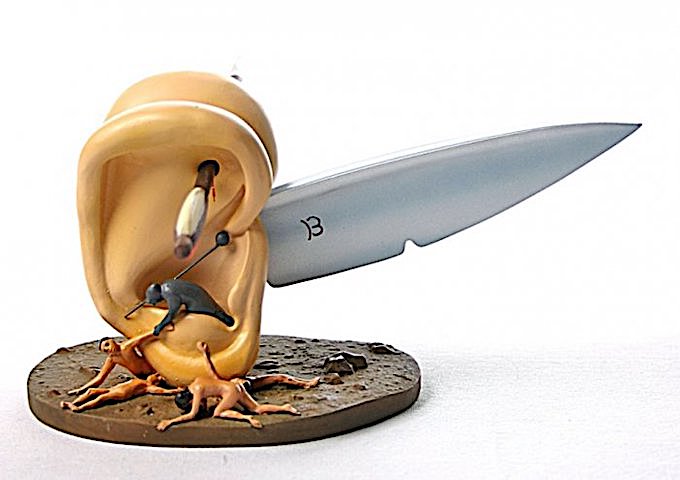

John Coltrane Draws a Picture Illustrating the Mathematics of Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness