At first glance, Madame Bovary and Blue Velvet would seem to have little in common, as would their creators. But the artistic life Gustave Flaubert led and the one David Lynch now leads share a basic precept: “Be regular and orderly in your life,” as the former once put it, “so that you may be violent and original in your work.” Lynch has spoken about his ways as an artistic creature of habit many times over the years, as demonstrated by the interview clip above. “Some people have heard the story that I went to Bob’s Big Boy for seven years every day at 2:30 and had the same thing,” he told Jay Leno in 1992. “That was my longest habit pattern, I think.”

Lynch’s regularity at that Los Angeles burger joint is just one of the routines that has structured his existence. “I like habitual behavior because it’s a known factor,” he says, “and then your mind is free to think about other things.” When life has an order, he later told Charlie Rose, “then you’re free to mentally go off any place. You’ve got a safe sort of foundation, and a place to spring off from.”

More recently, on a phone Q&A for the David Lynch Foundation, the auteur described his routine thus: “I wake up and I brush my teeth and I use the bathroom. Then I have a cappuccino and some cigarettes. Then I mediate, and then I have either some amrit nectar or a small smoothie with protein powder and blueberries and peaches. And then I go to work.”

However contradictory they may seem, Lynch’s long-standing twin loves of smoking and meditation both express themselves as routine actions. And if the backgrounds of his Youtube videos — including his little-varying daily Los Angeles weather reports — are anything to go by, he performs them in the kind of uncluttered physical space he’s long preferred: “The purer the environment,” as he puts it, “the more fantastic the interior world can be.” His 1980s and 90s comic strip The Angriest Dog in the World took place in such an environment, its nearly unchanging visuals and increasingly bizarre text an artistic correlative to his ideas about daily life and the imagination. But whatever their interest in his methods, Lynch’s fans want to know one thing above all: what the imagination of this least angry of all artists will bring forth next.

Related Content:

An Animated David Lynch Explains Where He Gets His Ideas

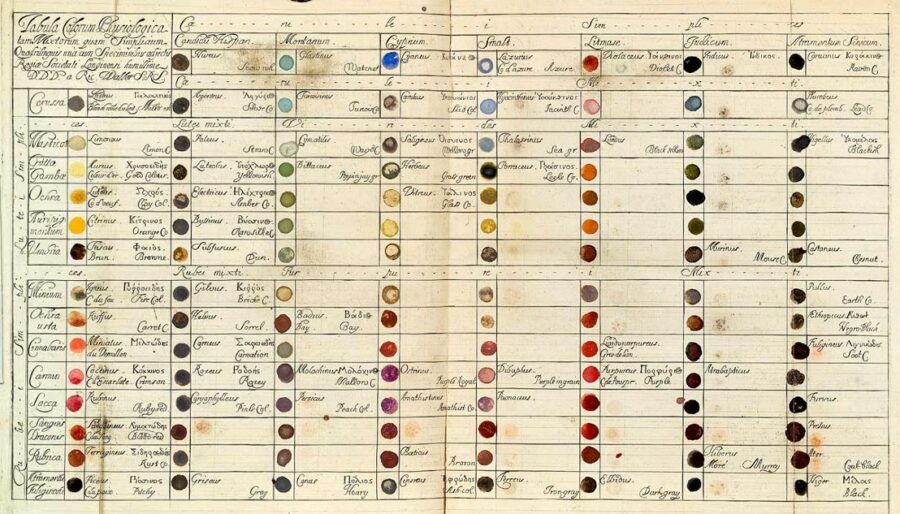

The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People, Presented in an Interactive Infographic

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.