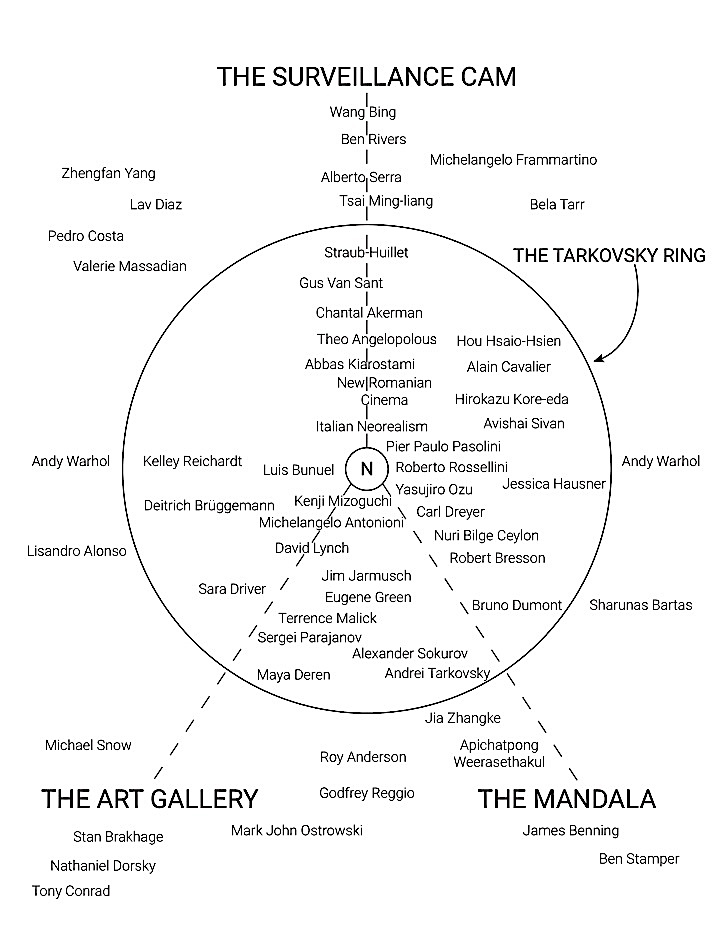

The dozens of filmmakers in the diagram above belong to a variety of cultures and eras, but what do they have in common? Some of the names that jump out at even the casual filmgoer — Andrei Tarkovsky, Jim Jarmusch, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Terrence Malick — may suggest a straightforward connection: cinephiles love them. Of course, not every cinephile loves every one of these directors, and indeed, bitter cinephile arguments rage about their relative merits even as we speak. But in one way or another, all of them are taken seriously as auteurs by those who take film seriously as an art form — and not least by Paul Schrader, one of the most serious auteur-cinephiles alive.

Schrader first made his name as a film critic, with his 1972 book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. In it he argues that the work of Yasujirō Ozu, Robert Bresson, and Carl Theodor Dreyer have in common a quality that quite literally “transcends” their differences in origin.

This transcendental style in film “seeks to maximize the mystery of existence; it eschews all conventional interpretations of reality: realism, naturalism, psychologism, romanticism, expressionism, impressionism, and, finally, rationalism.” It “stylizes reality by eliminating (or nearly eliminating) those elements which are primarily expressive of human experience, thereby robbing the conventional interpretations of reality of their relevance and power.”

45 years on, Schrader revisits this concept in the Toronto International Film Festival interview clip above. “Most movies lean toward you. They lean toward you aggressively with their hands around your throat, trying to grab every second of your attention.” But transcendental films “lean away from you, and they use time — and as other people would call it, boredom — as a technique.” They linger on the everyday, the uneventful, the repetitive. Used adeptly, this “withholding device” is a way of “activating” viewers and their attention. Then comes the “decisive action,” the moment in which the film does “something unexpected”: the “big blast of Mozart” at the end of Bresson’s Pickpocket, the “big blast of emotion” at the end of an otherwise reserved Ozu picture. “What are you going to do with it, now that he has totally conditioned you not to expect it?”

In the new edition of Transcendental Style in Film published in 2018, Schrader includes the diagram at the top of the post. It illustrates the three major directions in which filmmakers have departed from traditional narrative, represented by the N at the center. Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer all go off toward the meditative “mandala.” Abbas Kiarostami, Gus Van Sant, and the Italian neorealists start on path that leads to the “surveillance cam,” with its unblinking eye on an unchanging patch of reality. The likes of Kenji Mizoguchi, Michelangelo Antonioni, and David Lynch point the way to the audiovisual abstraction of the “art gallery.” Floating around these aesthetic end points are the names of filmmakers known for the “difficulty” of their work: Stan Brakhage, Wang Bing, James Benning.

Their work resides well past what Schrader calls the “Tarkovsky Ring,” named for the auteur of Mirror, Stalker, and Nostalghia. When an artist passes through the Tarkovsky Ring, as Schrader put it to Indiewire, “that’s the point where he is no longer making cinema for a paying audience. He’s making it for institutions, for museums, and so forth.” Within the Tarkovsky Ring appear a fair few adventurous directors still working today, like Hirokazu Kore-eda, Kelly Reichardt, Alexander Sokurov, and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Schrader has neglected to include his own name on the diagram, perhaps leaving his exact placement as an exercise for the reader. He certainly belongs on there somewhere: after all, some critics have called his last feature First Reformed his most transcendent yet.

Related Content:

The Exhilarating Filmmaking of Robert Bresson Explored in Eight Video Essays

How One Simple Cut Reveals the Cinematic Genius of Yasujirō Ozu

Four Video Essays Explain the Mastery of Filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami (RIP)

Andrei Tarkovsky Reveals His Favorite Filmmakers: Bresson, Antonioni, Fellini, and Others

Watch Online The Passion of Joan of Arc by Carl Theodor Dreyer (1928)

The 5 Essential Rules of Film Noir

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.