When Jeanette Ng gave her acceptance speech at the 2019 Joseph W. Campbell awards (now called the Astounding Award for Best New Writer), she described “Golden Age” editor Campbell as “a fascist” who “set a tone of science fiction that still haunts the genre to this day. Sterile. Male. White.” The list of Hugo winners this year show how much the situation is changing. Ng herself won a Hugo for her Campbell speech. (The unpleasant performance of the awards’ online presenter sadly got more headlines than the winners.)

Yet popular canons of sci-fi, even “seemingly progressive books for their time,” Liz Lutgendorff writes, still contain a “pervasive sexism.” Campbell was hardly the only offender, but the charge certainly sticks to him. “The first science fiction anthologies were published during a backlash against first-wave feminism,” Wired explains. In response to growing women’s activism, “male editors such as John W. Campbell and Groff Conklin specifically excluded women from” the pages of Astounding Science Fiction’s popular anthology series and Conklin’s many best-ofs.

Prior to these powerful editors, “women writers were relatively common throughout the pulp era, and the proportion of women readers was even higher.” Lisa Yaszek, Professor of Science Fiction Studies at Georgia Tech, found that “at least 15 percent of the science fiction community were women—producers—and reading polls suggest that 40 to 50 percent of the readers were women.” These figures surprised even her. Many of the writers whom Campbell excluded were hugely popular during 1920s, influencing their contemporaries and inspiring readers.

One such writer, Clare Winger Harris, published her first short story “The Runaway World,” in the July 1926 issue of Weird Tales (after writing an earlier historical novel in 1923). That same year, she won third place in a story contest run by legendary Amazing Stories editor Hugo Gernsback, from whom the Hugo Awards take their name. She would go on to publish ten more stories in popular science fiction pulps, most of them for Gernsback. Then she disappeared from writing in 1930, ostensibly to raise her three sons.

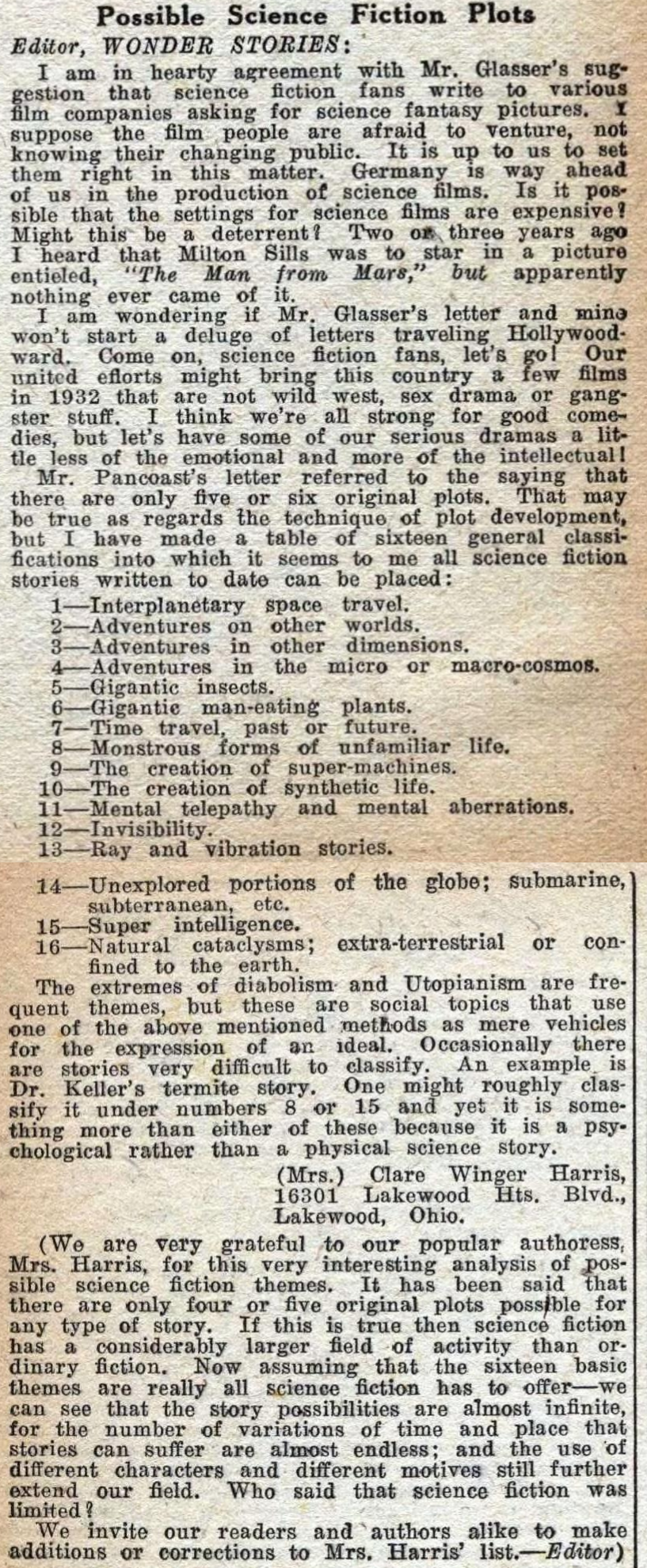

But she had more to say. In the August 1931 edition of Gernsback’s Wonder Stories, a letter from Harris appears in which she rallies the community to insist that Hollywood make sci-fi films. “Come on, science fiction fans, let’s go!” she writes, “Our united efforts might bring this country a few films in 1932 that are not wild west, sex drama or gangster stuff. I think we’re all strong for good comedies, but let’s have of our serious dramas a little less of the emotional and more of the intellectual.”

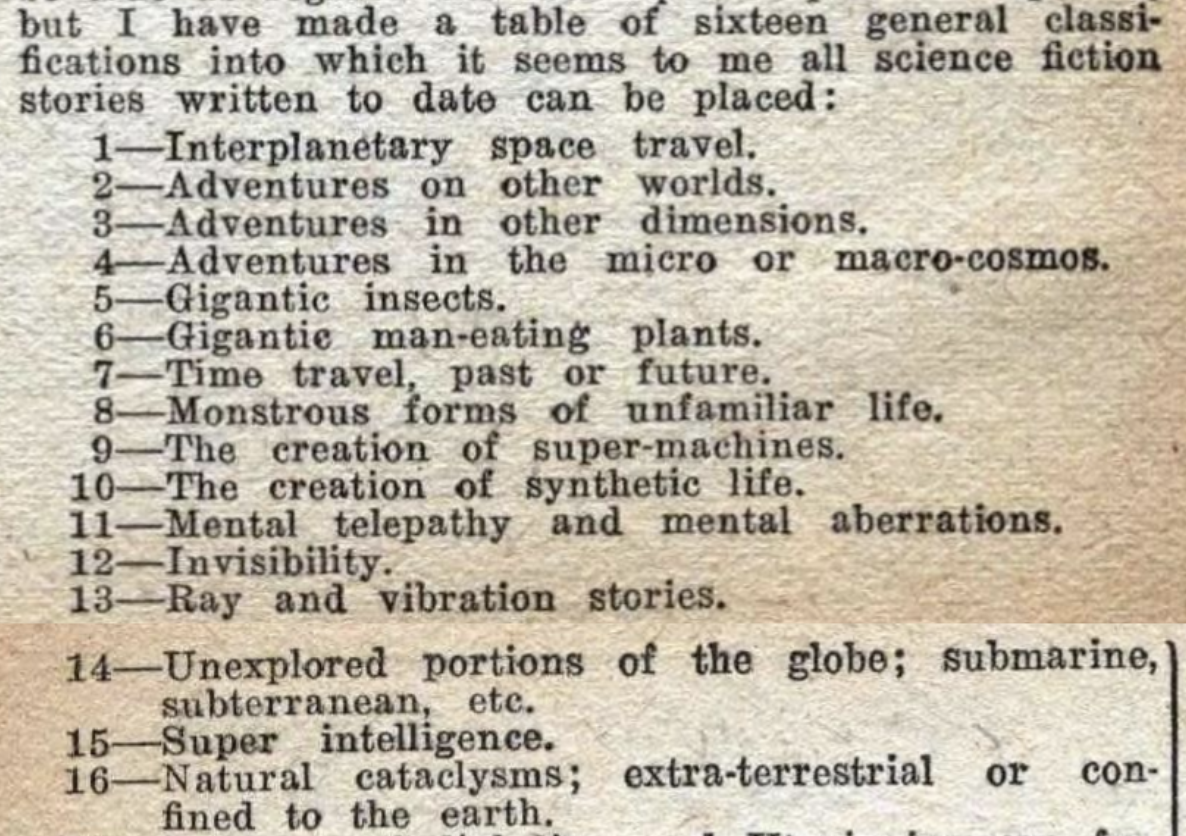

Harris goes on, in response to another reader letter, to correct the notion that “there are only five or six original plots.” (This number has varied over the ages from seven to thirty-seven). “That may be true as regards the technique of plot development,” writes Harris, “but I have made a table of sixteen general classifications into which it seems to me all science fiction stories written to date can be placed.” See it above.

Sci-fi author Doris V. Sutherland points to the redundancies and dated quaintness of much of the list. Giant insects have fallen out of fashion. “A number of the categories speak of the technological level of the day. The inclusion of ‘ray and vibration stores’ harks back to an era when the unseen effects of various electro-magnetic waves had only recently been grasped by researchers.” Moreover, the atomic age was yet to dawn. After it, “the idea of a man-made apocalypse would become rather more topical.”

The status of Harris’s letter as a “time capsule” that summarizes the “dominant themes in SF” at the time documents her keen appreciation for, as well as innovation on, those themes. She was valued for this talent by many in the field, Gernsback included. Upon learning she had won third prize in the 1926 Amazing Stories contest, he “gave praise,” Brad Ricca writes at LitHub, “couched in the cultural moment”—as well as indicative of his own biases.

That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest, for, as a rule, women do not make good scientification writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited. But the exception, as usual, proves the rule, the exception in this case being extraordinarily impressive.

These insulting beliefs did not prevent Gernsback from continuing to publish Harris’s work, nor any of women whose writing he approved. (He also helped make Campbell’s career.) Some have found it remarkable that Harris published under her own name rather than a male pseudonym, but Yaszek argues this was fairly common at the time. In fact, several male authors published under female pseudonyms. (Gernsback himself once adopted the moniker “Grace G. Hucksnob.”)

As women writers were edged out of science fiction during Campbell’s reign in the 1930’s, Harris retreated. Her only published literary productions were the 1931 letter and a short story that again proves her status as a pioneer. Her last story original story “appeared in 1933 in the fifth and last issue of a stapled, mimeographed pamphlet called Science Fiction that had a print run of maybe—maybe—50 issues,” Ricca writes. The story had been solicited by the tiny magazine’s editors, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, major Harris fans who would, of course, “go on to create Superman, the most recognized science fiction character on the planet.”

Learn more about Harris’s fascinating life—including her father’s brief stint as a Gernsback-influenced sci-fi novelist and her status as an early American convert to Buddhism before her death in 1968—at Ricca’s excellent LitHub investigation. See her full letter above.

Related Content:

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness