We read much about the role of Japanism in the art of late 19th Europe and North America. “The craze for all things Japanese,” writes the Art Institute of Chicago, “was launched in 1854 when American Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to recommence international trade after two centuries of virtual isolation.” Britain, the Continent, and the U.S. were awash in Japanese art and artifacts and ideas about the pre-industrial purity of Japanese forms proliferated. “Westerners were… drawn to traditional Japanese artistic expression because of its ties to the natural world. Japanese artists in all media treated the subjects of birds, flowers, landscapes, and the seasons.”

Westerners like Louis Comfort Tiffany emulated these patterns in their designs, and they appeared in the work of van Gogh and Gauguin. We may be familiar with how much the admiration for Japanese woodcuts, furniture, architecture, and poetry influenced Impressionism, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and early 20th century Modernism.

We may not know that the influence was mutual, with Japanese artists developing their own forms of Art Deco, European-influenced Modernism and a nationalist Japanese Arts and Crafts Movement called “Mingei” that was heavily inspired by earlier British artists who had themselves been inspired by the Japanese.

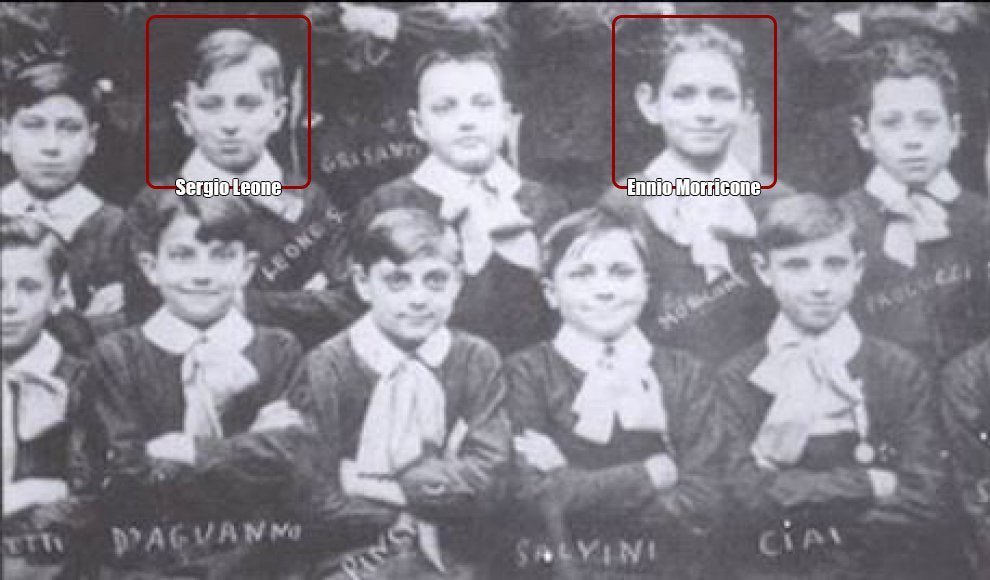

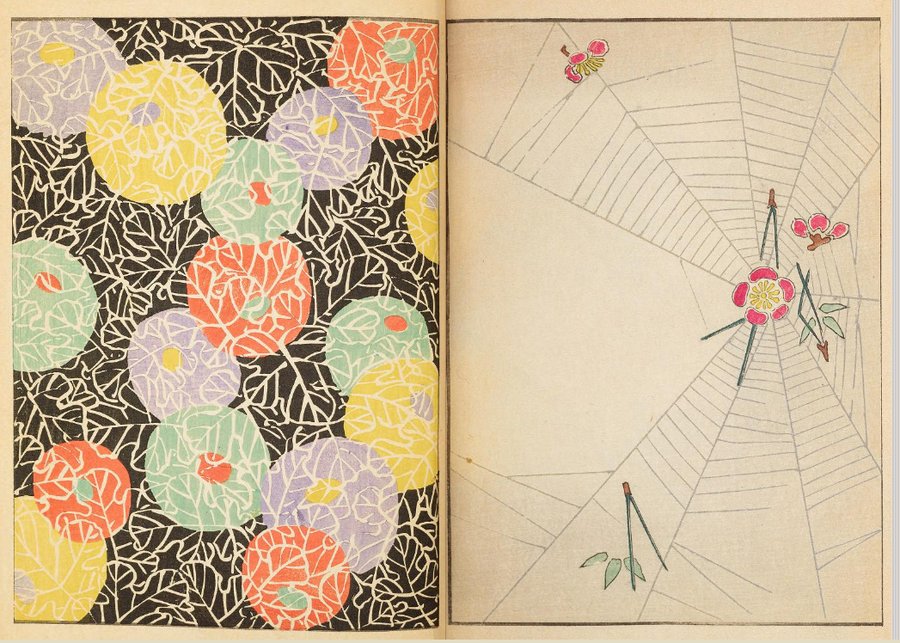

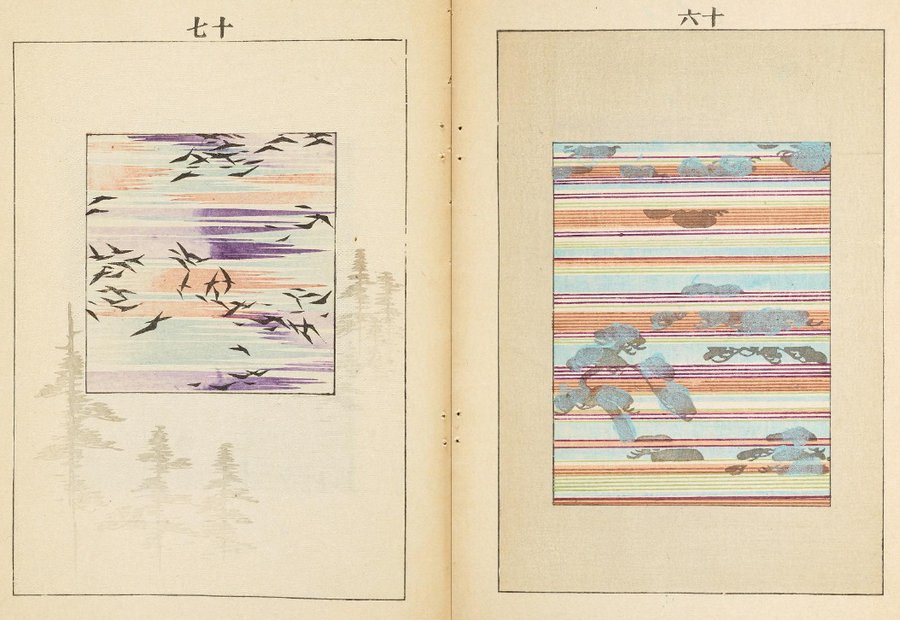

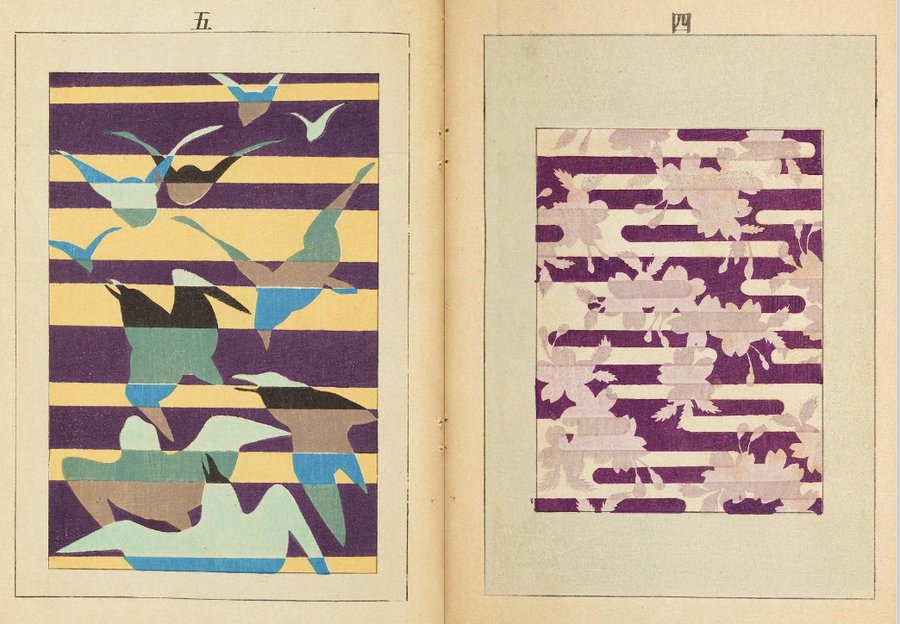

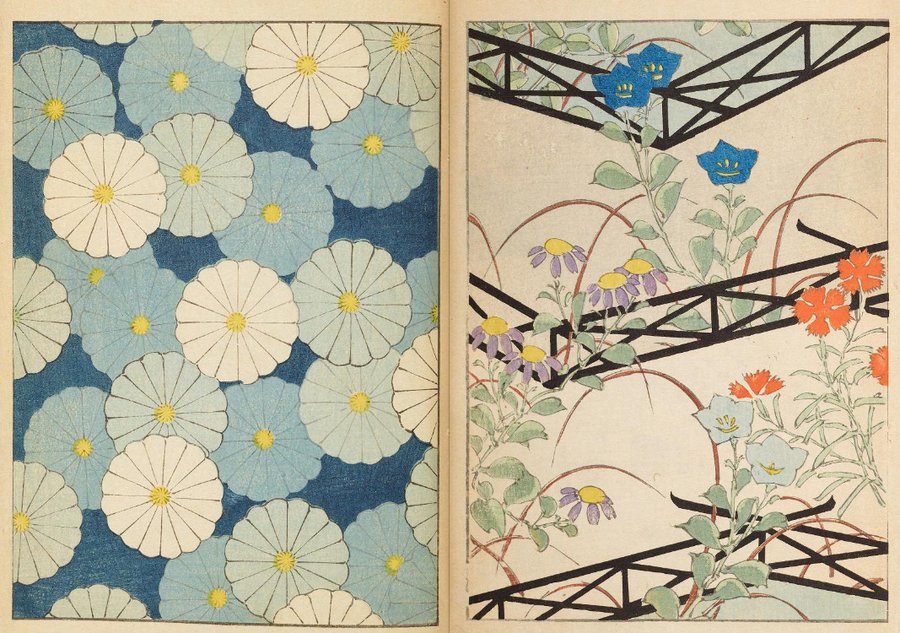

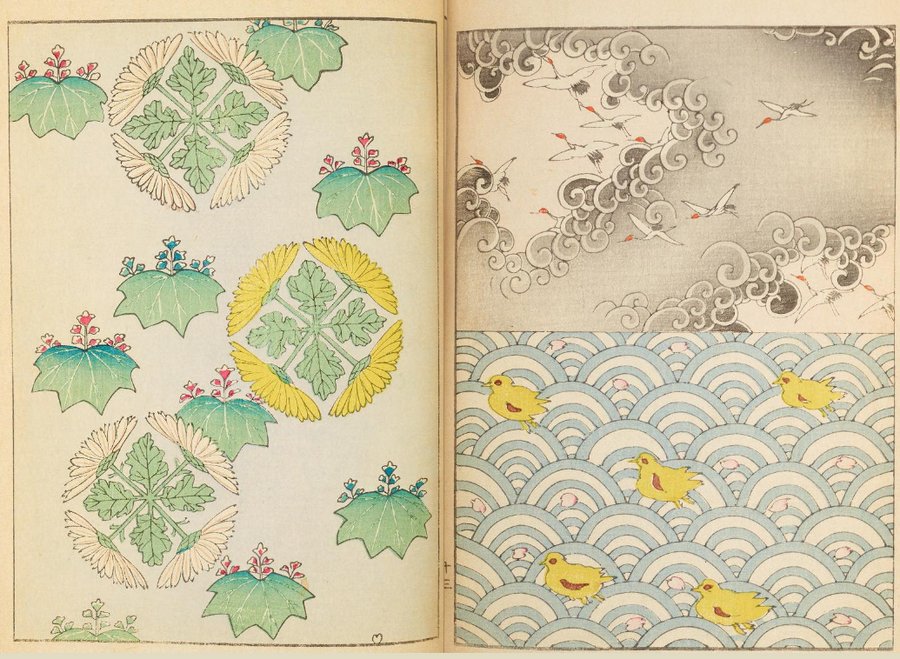

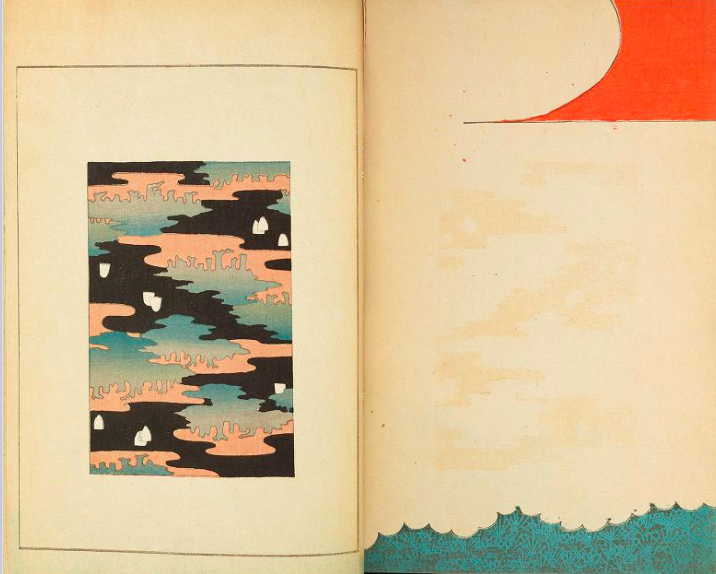

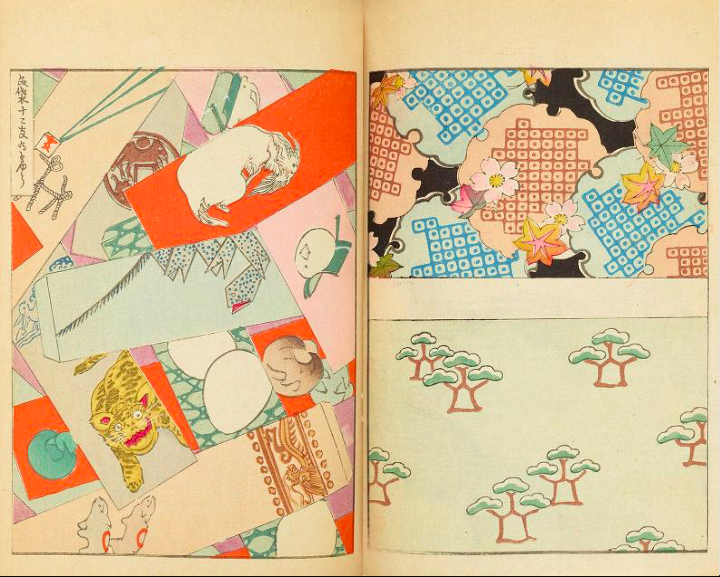

An earlier example of the cross-cultural exchange in the arts between Europe and Japan can be seen here in these prints from Shin-Bijutsukai (新美術海)… a Japanese design magazine that was edited by illustrator and designer Korin Furuya (1875–1910),” notes Spoon and Tamago. These images come from a collection of issues from 1901 to 1902, bound together in a huge 353-page design book (view it online at the Internet Archive or the Public Domain Review). We can see in the traditional images of flowers and birds the influence of industrial design as well as “hints of art nouveau and other influences of the time” from European graphic arts.

There was a reluctance among many Japanese artists to acknowledge their debts to Western artists, a symptom, writes Wendy Jones Nakanishi, professor at Shikoku Gakuin University, of “the ambivalence felt by many Japanese towards the rapid westernization of their country at the cost of the loss of indigenous cultural practices.” Despite the enormous popularity of Japanese art in Europe, “the ambivalence was mutual.” Many appeared to feel that “the subtle beauty of the Japanese art threatened European claims to cultural supremacy” when it appeared in Victorian exhibitions in London and elsewhere.

These fears aside, the meeting of many cultures in the exchanges between Europe and Japan helped to revitalize the arts and shake off stagnant classical traditions while responding in dynamic ways to rapid industrialization. The emphasis on folk and decorative art, brought into the realm of fine art, was culturally transformative in Europe. In Japan, the stylizations of modernist painting disrupted traditional scenes and techniques, as in the woodblock prints here and in the several hundred more in various issues of the monthly magazine. See them all at Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Advertisements from Japan’s Golden Age of Art Deco

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness