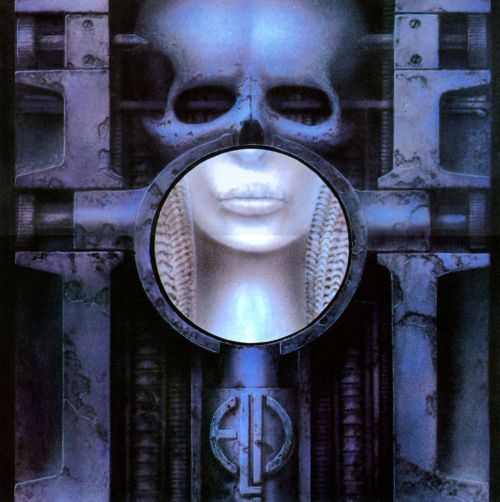

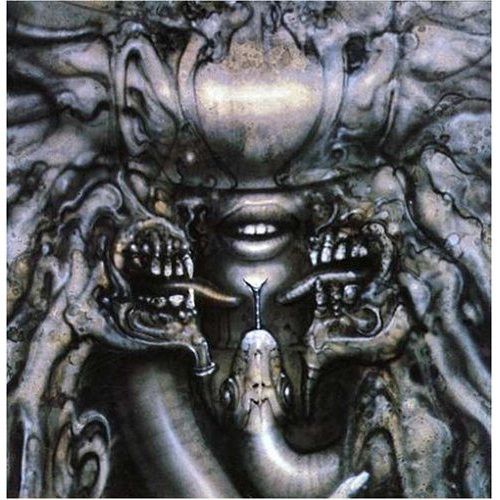

The work of H.R. Giger is immensely powerful. Giger’s amazing cover for Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s album Brain Salad Surgery portrays a Gothic touch that could fit any heavy metal band at any time.

—Jimmy Page

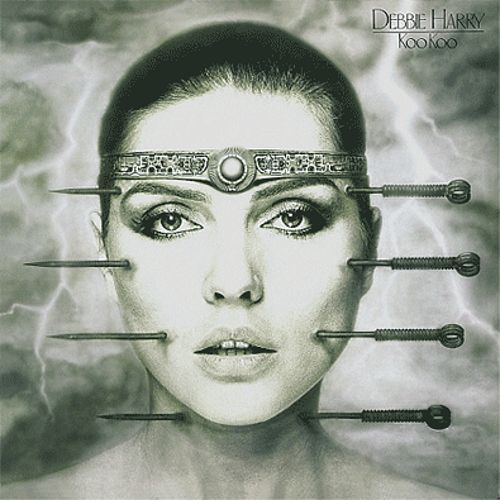

Swiss artist Hans Ruedi Giger is a genre unto his own, single-handedly inventing the biomechanical horror of the 1980s with his designs for Ridley Scott’s 1979 Alien, the film that launched him into international prominence and turned Debbie Harry on to his work. Meeting him the following year, the Blondie singer asked Giger to design the cover and music videos for her solo album, KooKoo.

The album was panned, but the cover ended up being as prescient as the film that preceded it. It would “see its influence in films like Hellraiser, the rise of what was called the ‘modern primitive’ movement, and help cultivate the dark masochistic character Harry would play in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome,” writes Ted Mills in an earlier Open Culture post. “It was a feeling that would flourish in the decadent ‘80s.”

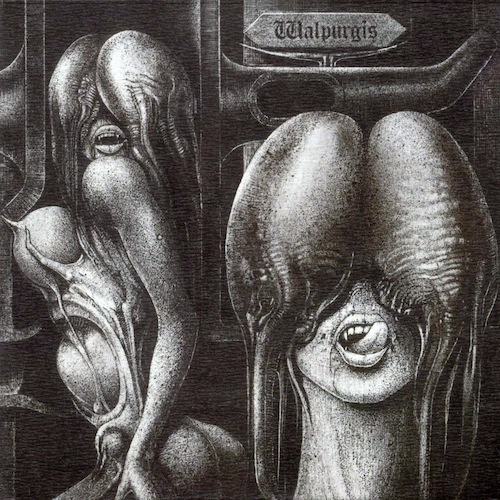

The record was also, in a way, “a throwback to Giger’s other famous record cover, the one for Emerson, Lake, and Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery” from 1973 (above). Ten years before Alien, Giger designed his first album cover, for a “proto-metal” band called The Shivers.

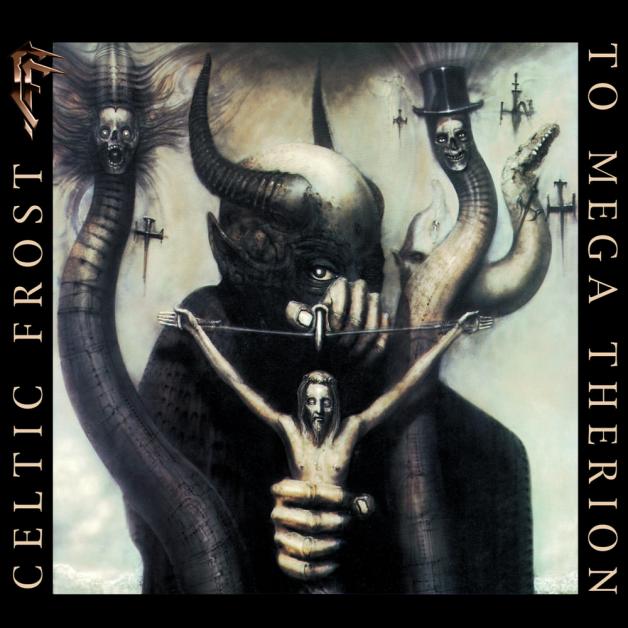

Their 1969 Walpurgis, features what look very much like Alien’s facehuggers. Giger had been having this nightmare for a long time. Years after these beginnings, due in large part to Alien and its sequels and the Debbie Harry cover, Giger became highly sought after by metal bands, from Celtic Frost to Danzig to Carcass.

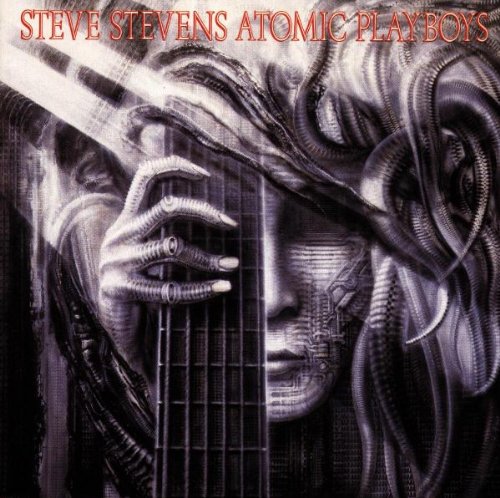

His work appears, however, on far more album covers than he would like. There have been “many small bands over the years,” he writes on his site, “presumably fans of mine, who had appropriated my artwork for their album and CD covers,” without getting permission. Giger himself has only created a few pieces specifically as album cover art, the last in 1989 for Steve Stevens’ Atomic Playboys. “Of the approximately 20 records on which my artwork has been seen over the last 30 years,” he writes, only a small number have been commissions. These include The Shivers, ELP, Harry, and Stevens.

All the other covers—those officially sanctioned, in any case—come from work Giger “made for myself, many years before, which the bands, later, licensed for their own use after seeing them in my books.” Though Giger himself is more of a jazz fan, his appeal to heavy metal is obvious. “Giger’s style of adding a surrealist twist to mechanical and biological scenes,” writes Allmusic, “often with twisted sexual undertones—was immediately identifiable,” and immediately identified a band as something seductively taboo and possibly deadly.

At least one use of his work got a band prosecuted. “Bay Area punks the Dead Kennedys included a poster of Giger’s Landscape #XX, also known as Penis Landscape (the image depicted rows of erect phalluses in coitus), in the packaging of their 1985 album Frankenchrist,” writes Rolling Stone, “and were subsequently put on trial for obscenity.”

Those who would misuse his work and violate his copyright may also find themselves in court. “It will,” he warns, “cost a lot more than if they had first contacted me, through my agent, to ask for permission.”

Related Content:

When Debbie Harry Combined Artistic Forces with H.R. Giger

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness