Since his death 56 years ago, Yasujirō Ozu has only become more and more often referenced as a locus of greatness in Japanese cinema. Almost without exception, his exegetes explain the power of his films first through their deceptive simplicity. His movies may look and play like simple midcentury domestic dramas, each bearing a strong resemblance to the one before, but within these rigid thematic and aesthetic strictures, Ozu achieves transcendence. In fact, before becoming a filmmaker in his own right Paul Schrader elevated Ozu into a trinity alongside Robert Bresson and Carl Theodor Dreyer in his 1972 book Transcendental Style in Film.

“Perhaps the finest image of stasis in Ozu’s films is the lengthy shot of the vase in a darkened room near the end of Late Spring,” Schrader writes, citing the 1949 picture usually counted among Ozu’s best. “The father and daughter are preparing to spend their last night under the same roof; she will soon be married. They calmly talk about what a nice day they had, as if it were any other day. The room is dark; the daughter asks a question of the father, but gets no answer. There is a shot of the father asleep, a shot of the daughter looking at him, a shot of the vase in the alcove and over it the sound of the father snoring. Then there is a shot of the daughter half-smiling, then a lengthy, ten-second shot of the vase again, and a return to the daughter now almost in tears, and a final return to the vase.”

Some viewers see the vase as an inexplicable inclusion, especially at such a charged moment. Schrader sees it as stasis itself, “a form which can accept deep, contradictory emotion and transform it into an expression of something unified, permanent, transcendent.” In the video essay at the top of the post, Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, examines for himself the place of the vase in Late Spring, in Ozu’s style more broadly, and in the body of critical work surrounding Ozu’s oeuvre.

To Puschak’s mind, the various readings of the vase by Schrader and others “speak to the unique power that Ozu has, that he developed over his long career. His style may appear simple, but is in fact so fine-tuned, so carefully calibrated, that he has the power to overwhelm the viewer, to launch a thousand interpretations with a single cut.”

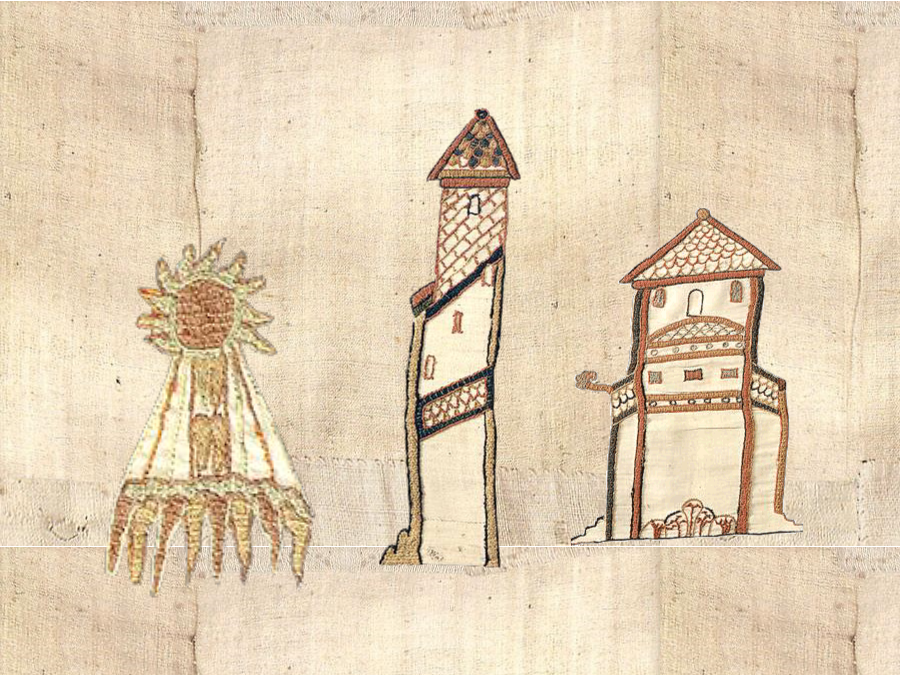

Late Spring features performances by Ozu regulars Chishū Ryū and Setsuko Hara, both of them inhabiting the kind of characters for which the director relied on them: Ryū the good-natured but firm father, Hara the by turns melancholic and optimistic but ultimately dutiful daughter. These are archetypal Ozu people, and the vase is an archetypal Ozu object, as much so as the recurring red tea kettle Ozu enthusiasts delight in spotting. Those fans will understand the appearance of the vase as a kind of “pillow shot,” the term used to describe those visual moments in all of Ozu’s pictures that have nothing to do with plot or character and everything to do with rhythm and reflection. They depict kettles and vases, but also pagodas, clothesline, street signs, smokestacks — things, not people, but things that, in their context, underscore Ozu’s powerful humanity.

Related Content:

An Introduction to Yasujiro Ozu, “the Most Japanese of All Film Directors”

How David Lynch Manipulates You: A Close Reading of Mulholland Drive

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.