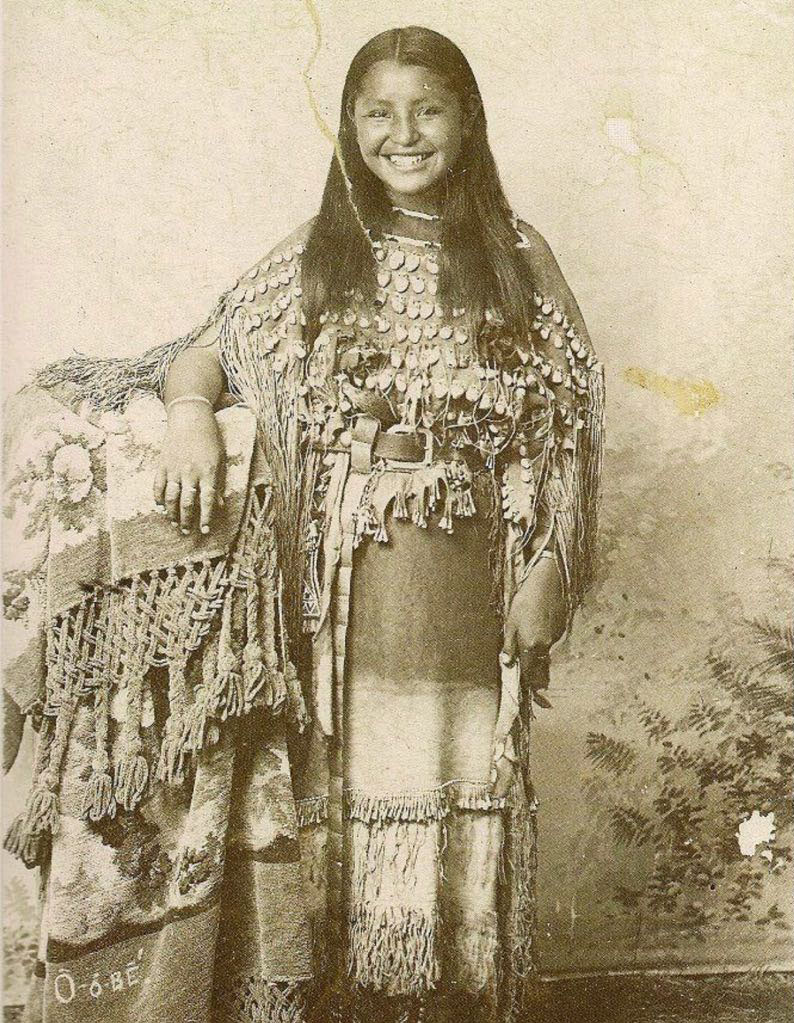

Just look at this photo. Just look at this young girl’s smile. We know her name: O‑o-be’, according to the Smithsonian. And we know that she was a member of the Kiowa tribe in the Oklahoma Territory. And we know that the photo was taken in 1894. But that smile is like a time machine. O‑o-be’ might just as well have donned some traditional/historical garb, posed for her friends, and had them put on the ol’ sepia filter on her camera app.

But why? What is it about the smile?

For one thing, we are not used to seeing them in old photographs, especially ones from the 19th century. When photography was first invented, exposures could take 45 minutes. Having a portrait taken meant sitting stock still for a very long time, so smiling was right out. It was only near the end of the 19th century that shutter speeds improved, as did emulsions, meaning that spontaneous moments could be captured. Still, smiling was not part of many cultures. It could be seen as unseemly or undignified, and many people rarely sat for photos anyway. Photographs were seen by many people as a “passage to immortality” and seriousness was seen as less ephemeral.

Presidents didn’t officially smile until Franklin D. Roosevelt, which came at a time of great sorrow and uncertainty for a nation in the grips of the Great Depression. The president did it because Americans couldn’t.

Smiling seems so natural to us, it’s hard to think it hasn’t always been a part of art. One of the first things babies learn is the power of a smile, and how it can melt hearts all around. So why hasn’t the smile been commonplace in art?

Historian Colin Jones wrote a whole book about this, called The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris, starting with a 1787 self-portrait by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun that depicted her and her infant. Unlike the coy half-smiles as seen in the Mona Lisa, Madame Le Brun’s painting showed the first white, toothy smile. Jones says it caused a scandal–smiles like this one were undignified. The only broad smiles seen in Renaissance painting were from children (who didn’t know better), the “filthy” plebeians, or the insane. What had happened? Jones credits the change to two things: the emergence of dentistry over the previous hundred years (including the invention of the toothbrush), and the emergence of a “cult of sensibility and politeness.” Jones explains this by looking at the heroines of the 18th century novel, where a smile meant an open heart, not a sarcastic smirk:

Now, O‑o-be’ and Jane Austen’s Emma might have been worlds apart, but so are we–creatures of technology, smiling at our iPhones as we take another selfie–from that Kiowan girl in the Fort Sill, Oklahoma studio of George W. Bretz.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020.

Related Content:

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838–2019)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

A timeless smile,

is her name O‑o-dee or O‑o-bee(as written on the picture)?

It looks like Ō‑ō-BĒ’ written on the photo, but according to summary notes from the Smithsonian website, her name was O‑o-dee. Either might be a typo, an error from what was heard by the person writing the name, or a difference in writing styles. Unfortunately, I don’t know more

Hi there,

We noticed that this post is getting a lot of visits today, but we couldn’t tell where visitors are coming from? Was Google News sending you here? Or was it something else?

Thanks for letting us know,

OC

This article was on my Google news feed.

Beautiful! Rare to see a smile in 19th Century photos.

Toothbrushes were not invented recently. I think you meant the modern toothbrush with synthetic brissels. Humanity has been brushing their teeth for centuries.

I remember seeing an early 20th century film (1917–18) of my great grandmother caring for my Grandfather as a baby. She was full-on smile, smile, smile, but that was motion, which for the time, was new. I think there are a few examples of late 19th century humans smiling for motion cameras when film was really very new tech and still experimental. It is such an interesting time-machine affect.

Hello, I indeed came through Google’s suggested news articles. Beautiful photo!

When I opened Google, it was one of the articles offered. Wonderful. I thought it was a hoax, a modern girl dressed up. But curiousity got me to read it. Love learning new things.

This beautiful Indian maiden must have been in the family of Miranda Lambert.…Am i right don’t y’all get it . The smile the hands!!😀🎸

I’ve seen this before a number of times. I wonder what O‑o-be’s later life was like. She could’ve very been around into or beyond the 1950s.

Such a pretty young woman. The smile just lights up her face! How interesting it would be to have seen smiles on more faces in early photographs.

Yes, this is such an iconic and indeed beautiful photo, L wonderful what was going through that girls life at the time. One thing l can assure you is she is bright brave and confident. Bless her God beautiful soul, this picture is timeless

This is how young women / girls should be? Proud of how they look, who they are; while looking forward eagerly to a bright future.

This photo is completely bogus. In the first place Indians never smiled like that. Secondly I’ve seen many many pictures of Indians and never seen a girl that is this attractive. It’s bogus!!

CGI photo

What a cutie! What a nice thing to find.

The “Dee vs. Bee” could be a difference between phonetic and proper spellings or the “sound” the letter makes. I know in the Osage language when using the Roman lettering system a D can be pronounced like a B… if that helps.

I come to this page via the Openculture.com newsletter. All the way from Pahiatua in New Zealand. We have old photo’s of Maori and Pacific peoples in our museums here but I don’t recall seeing such a great smile and happy eyes like O‑o-bee. Just beautiful.

The girl is wearing a dress for a jingle dance. It is covered with coins and little pieces of metal that “jingle” as she dances.

It was in my Google news feed. Nice post! Thank you!

Google suggested it, that smile lured me in.

It has 4th grade school picture vibes.

Same. Google news feed.

The article states that exposure times were about 45 minutes, is it possible they meant “4–5 minutes”? A quick Google search says the popular processes of 1850 on had 3–5 minute exposure times. Holding still and smiling for 3–5 minutes would be damn hard- but doing so for 45 minutes would be nearly impossible.

That savage wouldve made wonderful slave to my ancestors

My biological mother is from

Oklahoma, with supposed native ties, and my daughter looks just like this girl. Thank you for publishing this cause it is such a close resemblance I will for sure follow this up. You may have inadvertently help me. Thank you for what you do

Filthy white Europeans genocided her entire race and now you sick people want to admire her smile.

Google News! :)

Okay I have never seen such outrageous weirdness in my life… Either you’re trolling or in a cult

That’s really cool, Christina!

Oh she was so gorgeous.

Beautiful young lady, I do understand why the pictures of native Americans smiling are very rare though. We destroyed their culture,way of life and took the land. Not much reason to smile about if you think about it.