An Analysis of Quentin Tarantino’s Films Narrated (Mostly) by Quentin Tarantino

For nearly thirty years, the work of Quentin Tarantino has inspired copious discussion among movie fans. Some of the most copious discussion, as well as some of the most insightful, has come from no less avid a movie fan than Tarantino himself. Every cinephile has long since known that the man who made Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Jackie Brown — and more recently pictures like Django Unchained, The Hateful Eight, and Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood — is one of their own. Now the subject of numerous video essays, Tarantino could, in another life, have become that medium’s foremost practitioner. In the Now You See It video essay above, we have the next best thing: an analysis of Tarantino’s work narrated, for the most part, by the man himself.

“It’s as if a couple of movie-crazy young Frenchmen were in a coffee house, and they’ve taken a banal American crime novel and they’re making a movie out of it based not on the novel, but on the poetry they’ve read between the lines.” So goes New Yorker critic Pauline Kael’s review of Jean-Luc Godard’s Bande à part — as remembered by Tarantino in an interview in the 2000s.

These and other such clips comprise “Quentin Tarantino and the Poetry Between the Lines,” or at least they comprise the parts that don’t come straight from Tarantino’s films or the films that inspired them. From Bande à part Tarantino took not just the name of his production company but also the imperfect style of dancing he had John Travolta and Uma Thurman show off in Pulp Fiction, one of the many acts of cinematic “stealing” to which he gladly cops.

In describing the rule-breaking work of Godard, the first big cinephile-filmmaker, Kael inadvertently bestowed a revelation upon Tarantino: “That’s my aesthetic!” he remembers thinking. “That’s what I want to achieve!” That goal has inspired Tarantino to a number of acts of cultural transposition, and this video essay also brings together the comments several other figures have made about his achievement: Inglourious Basterds star Christoph Waltz remarks on the characteristic way that Tarantino, “the product of the culture that made the Western possible at all,” would “take the genre once removed into the Italian and bring it back to America” as he does in his repatriated spaghetti Western The Hateful Eight. To that picture, and to Quentin Tarantino’s greater cinematic project, applies the observation Gene Siskel made on Pulp Fiction just as it was becoming a cultural phenomenon in its own right: “Like all great films, it criticizes other movies.”

Related Content:

How Quentin Tarantino Steals from Other Movies: A Video Essay

Quentin Tarantino Explains How to Write & Direct Movies

Quentin Tarantino Picks the 12 Best Films of All Time; Watch Two of His Favorites Free Online

The Power of Food in Quentin Tarantino’s Films

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

An Emotional Journey into the Heart of August Sander’s Iconic Photograph, “Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance”

The portrait is your mirror. It’s you. —August Sander

A picture is worth a thousand words, and compelling portraits that speak eloquently to a critical moment in history often earn many more than that.

Author John Green’s thoughtful Art Assignment investigation into Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, August Sanders’ 1914 photograph, taps into our need to interpret what we’re looking at.

The descriptive title (the piece is alternatively referred to as Young Farmers) offers some clues, as does the date.

The subjects’ youth and location—a remote village in the German Westerwald—suggest, correctly as it turns out, that they would soon be bound for what Green terms “another dance,” WWI.

Green has learned far more about the people in his favorite photo since he covered it in a 2‑minute segment for his vlogbrothers channel below.

Much of the shorter video’s narration carries over to the Art Assignment script, but this time, Green has the help of “a community of problem solvers” who contributed research that fleshed out the narrative.

We now know the young farmers’ identities, actual occupations, what they did in the war, and their eventual fate.

Ditto their connection to photographer Sanders, who lugged his equipment on foot to the remote mountain path the friends would be traveling in finery made possible by the Second Industrial Revolution.

A consummate storyteller, Greene makes a meal out of what he has learned.

It would provide the basis for a helluva book…though here another author has beaten Green to the punch. Richard Powers’ novel, also titled Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, was a National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist in 1985.

Related Content:

The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826)

Take a Visual Journey Through 181 Years of Street Photography (1838–2019)

See the First Photograph of a Human Being: A Photo Taken by Louis Daguerre (1838)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Here latest project is an animation and a series of free downloadable posters, encouraging citizens to wear masks in public and wear them properly. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

This Is What The Matrix Looks Like Without CGI: A Special Effects Breakdown

Those of us who saw the The Matrix in the theater felt we were witness to the beginning of a new era of cinematically and philosophically ambitious action movies. Whether that era delivered on its promise — and indeed, whether The Matrix’s own sequels delivered on the franchise’s promise — remains a matter of debate. More than twenty years later, the film’s black-leather-and-sunglasses aesthetic may date it, but its visual effects somehow don’t. The Fame Focus video above takes a close look at two examples of how the creators of The Matrix combined traditional, “practical” techniques with then-state-of-the-art digital technology in a way that kept the result from going as stale as, in the movies, “state-of-the-art digital technology” usually has a way of guaranteeing.

By now we’ve all seen revealed the mechanics of “bullet time,” an effect that astonished The Matrix’s early audiences by seeming nearly to freeze time for dramatic camera movements (and to make visible the eponymous projectiles, of which the film included a great many). They lined up a bunch of still cameras along a predetermined path, then had each of the cameras take a shot, one-by-one, in the span of a split second.

But as we see in the video, getting convincing results out of such a groundbreaking process — which required smoothing out the unsteady “footage” captured by the individual cameras and perfectly aligning it with a computer-generated background modeled on a real-life setting, among other tasks — must have been even more difficult than inventing the process itself. The manual labor that went into The Matrix series’ high-tech veneer comes across even more in the behind-the-scenes video below:

In the third installment, 2003’s The Matrix Revolutions, Keanu Reeves’ Neo and Hugo Weaving’s Agent Smith duke it out in the pouring rain as what seem like hundreds of clones of Smith look on. Viewers today may assume Weaving was filmed and then copy-pasted over and over again, but in fact these shots involve no digital effects to speak of. The team actually built 150 realistic dummies of Weaving as Smith, all operated by 80 human extras themselves wearing intricately detailed silicon-rubber Smith masks. The logistics of such a one-off endeavor sound painfully complex, but the physicality of the sequence speaks for itself. With the next Matrix film, the first since Revolutions, due out next year, fans must be hoping the ideas of the Platonically techno-dystopian story the Wachowskis started telling in 1999 will be properly continued, and in a way that makes full use of recent advances in digital effects. But those of us who appreciate the enduring power of traditional effects should hope the film’s makers are also getting their hands dirty.

Related Content:

The Philosophy of The Matrix: From Plato and Descartes, to Eastern Philosophy

The Matrix: What Went Into The Mix

Daniel Dennett and Cornel West Decode the Philosophy of The Matrix

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

50 Songs from a Single Year, Mixed Together Into One 3‑Minute Song (1979–89)

The concept of generations, as we currently use the term, would have made no sense to people living throughout most of human history. “Before the 19th century,” writes Sarah Leskow at The Atlantic, “generations were thought of as (generally male) biological relationships within families—grandfathers, sons, grandchildren and so forth.” The word did not describe common traits shared by, “as one lexicographer put it in 1863, ‘all men living more or less at the same time.’”

The theory was thoroughly ingested into mass culture, as anyone can tell from social media wars and the fixations of newspaper columnists. One such correspondent weighed in a few years ago with a contrarian take: “Your generational identity is a lie,” wrote Philip Bump at The Washington Post in 2015. (He makes an exception for Baby Boomers, for reasons you’ll have to read in his column.)

All this debunking is to the good. While scholars routinely investigate the origins of contemporary ideas, too often the rest of us take for granted that our present ways of seeing the world are timeless and eternal.

Yet, whether generations are a real phenomenon or a cultural construction, globalized mass media of the past several decades ensures that no matter where we come from, most people born around the same time will share some set of near-identical experiences—of listening to the same music, watching the same films, TV shows, etc. Given the way our thinking can be shaped by formative moments in pop culture, we’re bound to have a few things in common if we had access to Hollywood film and MTV. Maybe what most defines generations as we know them now is culture as commodity.

Take the video series featured here. Each one cuts together 50 songs released in a single year, beginning in 1979, along with video montages of some of the year’s most popular artists. Created by The Hood Internet, “a DJ and production duo from Chicago, known for their expertise in mashups and remixes,” the series could serve as a lab experiment to test the emotional reactions of people born at different times. We may have all heard these songs by now. But only those who heard them in their youth will have the nostalgic reactions we associate with generational memory, since music, as David Toop writes at The Quietus, is “a memory machine.”

Everyone else could stand to learn something about what the 80s looked and sounded like. As a historical period, it tends to get cast in a fairly narrow mold, with synthpop and hair metal defining the extent of 80s music. The pop music of the decade was fabulously diverse, with genres cross-pollinating in what turn out to be surprisingly harmonious ways in these mashup videos. The creators of the series worked their way up to 1987, and we get to see some dramatic shifts along the way that further complicate the idea of 80s music, even for those who heard these songs when they came out, and who have nine years of formative moments to go with them. See all of the videos on The Hood Internet’s YouTube channel.

Related Content:

1980s Metalhead Kids Are Alright: Scientific Study Shows That They Became Well-Adjusted Adults

A Soul Train-Style Detroit Dance Show Gets Down to Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” in the Late 80s

How a Recording Studio Mishap Created the Famous Drum Sound That Defined 80s Music & Beyond

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How Humphrey Bogart Became an Icon: A Video Essay

According to film theorist David Bordwell, there was a major change in acting styles in the 1940s. Gone was the “behavioral acting” style of the 1930s (the first full decade of sound film), where mental states were demonstrated not just through the face, but through body movement, and how actors just held themselves. Instead, in the 1940s there is a “new interiority, a kind of neutralization, of the acting performance, that’s intense, almost silent film-style.”

Part of this is due to increasingly convoluted, psychological narratives, including lots of voice-overs. Some of it was also due to studios hoping to achieve the psychological depth of novel writing.

In short, whatever the reasons in the 1940s, we got to watch characters think.

In Nerdwriter’s latest video essay, Evan Puschak examines the icon of 1940s male acting: Humphrey Bogart, whose skill and opportunity placed him at the right place and the right time for such a shift in styles. Think of Bogart and you think of his eyes and yes, the many moments where the camera lingers on his face and…we watch him think.

In hindsight it feels like he was waiting for this moment. Puschak picks up the tale with 1939’s The Return of Dr. X, which features a badly miscast Bogart as a mad scientist. But the actor had spent most of the 1930s playing a selection of bad guys, mostly gangsters. He was good at it. He was also a bit tired of the typecasting.

Also tired of of playing gangsters was George Raft, and that turned out to be good thing, because Raft turned down the lead role in the John Huston-written, Raoul Walsh-directed High Sierra. Huston and Bogart were friends and drinking buddies, and it was their friendship, plus Bogart convincing both Raft to turn down the role and Walsh to hire him instead, that led to a career breakthrough.

As Puschak points out, though Bogart was playing a gangster again, he brought to the character of Mad Dog Roy Earl a world-weariness and a vulnerable interior, and we see it in his eyes more than through his dialog.

In the same year Bogart played private detective Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, also a role that George Raft turned down. Bogart brought over to the character the cynicism and coolness of his gangster roles; it feels repetitive to say it was an iconic role, but it’s true—it’s a performance that ripples across time to every actor playing a private detective, who are either borrowing from it or riffing on it or turning it on its head. You wouldn’t have Columbo. You wouldn’t have Breathless either.

Did George Raft ever realize he was a sort of guardian angel for Bogart? Because for a third time, a role he turned down became a Bogart classic: Rick Blain in Casablanca (1942). As Puschak points out, it’s a difficult role as Rick is decidedly passive and casually mean for the first half, leaving people to their fate. It only works because we can see every decision Rick makes roiling behind Bogart’s eyes, and we know that eventually he will break and do the right thing.

As he got older and the 40’s turned into the ‘50s, Bogart began to play with these kind of characters. His prospector in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre turns wild-eyed with greed and madness; his writer in In a Lonely Place is suspected of murder, and Bogart plays him ever so slightly mad that we wonder if he might even be a killer. It is one of Bogart’s most uncomfortable performances, taking what had become familiar and friendly in his screen persona and twisting it.

He died in 1957, age 57, from the cancerous effects of a lifetime of smoking. What kind of roles might he have done if he had made it through the 60s and the 70s? Would the French New Wave directors have hired him? Would Scorsese or Altman or Coppola? Again, we can only wonder.

Related Content:

Beat the Devil: Watch John Huston’s Campy Noir Film with Humphrey Bogart (1953)

Lauren Bacall (1924–2014) and Humphrey Bogart Pal Around During a 1956 Screen Test

Jean-Paul Sartre Writes a Script for John Huston’s Film on Freud (1958)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

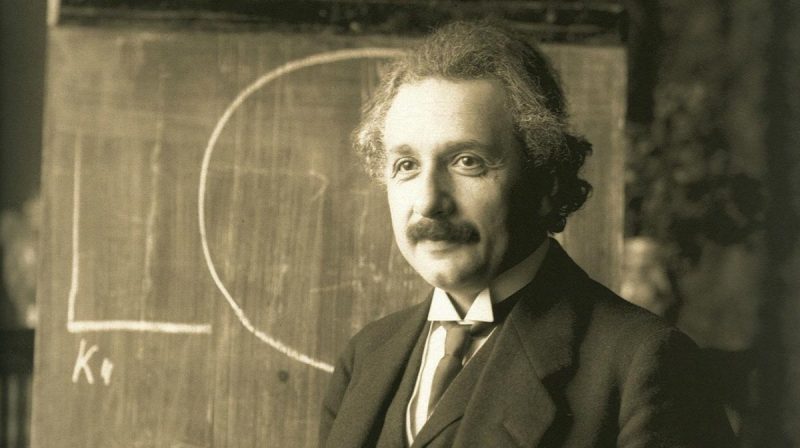

Albert Einstein Explains Why We Need to Read the Classics

Two pieces of reading advice I’ve carried throughout my life came from two early favorite writers, Herman Melville and C.S. Lewis. In one of the myriad pearls he tosses out as asides in his prose, Melville asks in Moby Dick, “why read widely when you can read deeply?” Why spread our minds thin? Rather than agonize over what we don’t know, we can dig into the relatively few things we do until we’ve mastered them, then move on to the next thing.

Melville’s counsel may not suit every temperament, depending on whether one is a fox or a hedgehog (or an Ahab). But Lewis’ advice might just be indispensable for developing an outlook as broad-minded as it is deep. “It is a good rule,” he wrote, “after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones.”

Many other famous readers have left behind similar pieces of reading advice, like Edward Bulwer-Lytton, author of notorious opener “It was a dark and stormy night.” As though refining Lewis’ suggestion, he proposed, “In science, read, by preference, the newest works; in literature, the oldest. The classic literature is always modern. New books revive and redecorate old ideas; old books suggest and invigorate new ideas.”

Albert Einstein shared neither Lewis’ religion nor Bulwar-Lytton’s love of semicolons, but he did share both their outlook on reading the ancients. Einstein approached the subject in terms of modern arrogance and ignorance and the bias of presentism, writing in a 1952 journal article:

Somebody who only reads newspapers and at best books of contemporary authors looks to me like an extremely near-sighted person who scorns eyeglasses. He is completely dependent on the prejudices and fashions of his times, since he never gets to see or hear anything else. And what a person thinks on his own without being stimulated by the thoughts and experiences of other people is even in the best case rather paltry and monotonous.

There are only a few enlightened people with a lucid mind and style and with good taste within a century. What has been preserved of their work belongs among the most precious possessions of mankind. We owe it to a few writers of antiquity (Plato, Aristotle, etc.) that the people in the Middle Ages could slowly extricate themselves from the superstitions and ignorance that had darkened life for more than half a millennium.

Nothing is more needed to overcome the modernist’s snobbishness.

Einstein himself read both widely and deeply, so much so that he “became a literary motif for some writers,” as Dr. Antonia Moreno González notes, not only because of his paradigm-shattering theories but because of his generally well-rounded public genius. He was frequently asked, and happy to volunteer, his “ideas and opinions”—as the title of a collection of his writing calls his non-scientific work, becoming a public philosopher as well as a scientist.

We might credit Einstein’s liberal attitude toward reading and education—in the classical sense of the word “liberal”— as a driving force behind his endless intellectual curiosity, humility, and lack of prejudice. His diagnosis of the problem of modern ignorance may strike us as grossly understated in our current political circumstances. As for what constitutes a “classic,” I like Italo Calvino’s expansive definition: “A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.”

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

Italo Calvino Offers 14 Reasons We Should Read the Classics

Virginia Woolf Offers Gentle Advice on “How One Should Read a Book”

The New York Public Library Creates a List of 125 Books That They Love

100 Novels All Kids Should Read Before Leaving High School

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Is It Rude to Talk Over a Film? MST3K’s Mary Jo Pehl on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #45

We live in a commentary culture with much appreciation for camp and snark, but something special happened in the early ’90s when Mystery Science Theater 3000 popularized this additive form of comedy, where jokes are made during a full-length or short film. Mary Jo Pehl was a writer and performer on MST3K and has since riffed with fellow MST3K alums for Rifftrax and Cinematic Titanic.

Mark, Erica, and Brian briefly debate the ethics of talking over someone else’s art and then interview Mary Jo about how riffs get written, developing a riffing style and a character that the audience can connect with (do you need to include skits to establish a premise for why riffing is happening?), riffing films you love vs. old garbage, the degree to which riffing has gone beyond just MST3K-associated comedians, VH-1’s Pop-Up Video, and more.

Follow Mary Jo @MaryJoPehl.

Here are a some links to get you watching riffing:

- For MST3K newbies, you might want to watch some episodes, nearly all of which are on YouTube. The AV Club has recommended its top ten episodes. Mark thinks a great introduction to the show (from a late season that features Mary Jo as a regular cast member) is S10E03 riffing a rare contemporary film, 1996’s Merlin’s Shop of Mystical Wonders. For a classic (i.e. featuring original host and creator Joel Hodgson) episode, S03E03’s Pod People is much beloved.

- Watch samples of Bridget and Mary Jo riffing the blockbuster Gravity, Mary Jo with Rifftrax founder (and former MST3K host) Mike Nelson riffing Mariah Carey’s Glitter, the two of them doing a full short at a Rifftrax Live event, and with Cinematic Titanic Live taking on Rattlers.

Different teams have different styles of riffing, so if you hate MST3K, you might want to see if you just hate those guys or hate the art form as a whole. The alums themselves currently work as:

- Rifftrax (Mike Nelson, Kevin Murphy, and Bill Corbett, who were the stars of the final MST3K seasons, but the new effort involves different writers. They riff both old B‑movies and Hollywood blockbusters like Twilight.

- Rifftrax Presents includes Bridget and Mary Jo (who among other things, are able to effectively treat shorts and films that aim to discuss “women’s issues”) as well as the very British Matthew J. Elliot and Ian Potter, Janet Varney and Cole Stratton, and Rifftrax writers Conor Lastowka and Sean Thomason.

- Joel Hodgson owns MST3K and recently did his final tour as a riffer, though that entirely new group will continue performing without him and just issued the Live Social Distancing Riff-Along Special. Joel led from behind the scenes the recent Netflix MST3K revival with host Jonah Rey.

- Frank Coniff and Trace Beaulieu (who participated with Mary Jo and Joel in Cinematic Titanic) tour as “The Mads,” which doesn’t seem to have any clips posted, but you can hear their podcast Movie Sign with the Mads.

- Groups influenced by MST3K that Mark checked out include Master Pancake Theater, Rangoon Riffs, The Guy with Glasses, Linkara, Snob Riffs, and The Last Angry Geek. Rifftrax allows groups like these to create and sell their own riffs.

Here are a few relevant articles:

- “ ‘Mystery Science Theater 3000’ at 30: How a Cult TV Show Changed Pop Culture” by Noel Murray

- “Color Commentary” by Tad Friend

- “ ‘Mystery Science Theater 3000’ Returns with New Blood for the Turkey Day Marathon” by Meredith Woerner

Also, PROJECT: RIFF is the website/database we talk about where a guy named Andrew figured out how many riffs per minute are in each MST3K episode, which character made the joke, and other stuff.

Learn more at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.