Even if you don’t know much about Korea, or indeed about film, it’s safe to say that you know at least one Korean film: Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, which has circled the world gathering acclaim and awards since its release last spring. First it won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, becoming the first Korean production to do so; more recently, it made film history even more dramatically at the Academy Awards. There it won Oscars not just for Best International Feature Film, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Director, but also Best Picture, becoming the first non-English-language film to do so. For many viewers, Parasite and its director seem to have come out of nowhere, but lovers of Korean cinema know full well that they come out of a rich tradition — and a robust industry.

Maybe you thrilled to Bong’s suspenseful, funny, and violent tale of class warfare as much as the Academy did. Maybe you’ve even seen the work of Bong’s contemporaries: Park Chan-wook, he of the controversial hit Oldboy; the even more transgressive Kim Ki-duk; the prolific Hong Sangsoo, with his Woody Allen-meets-Éric Rohmer sensibility.

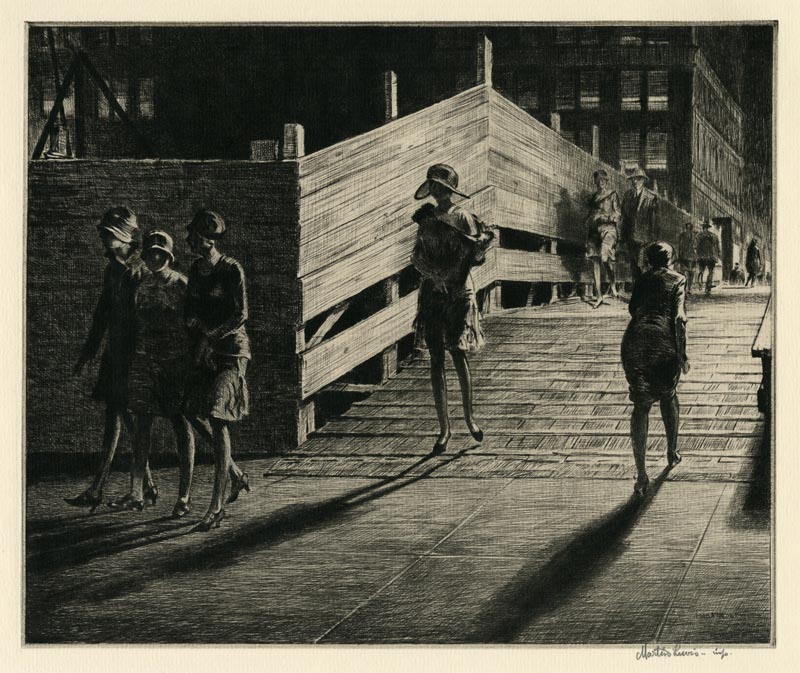

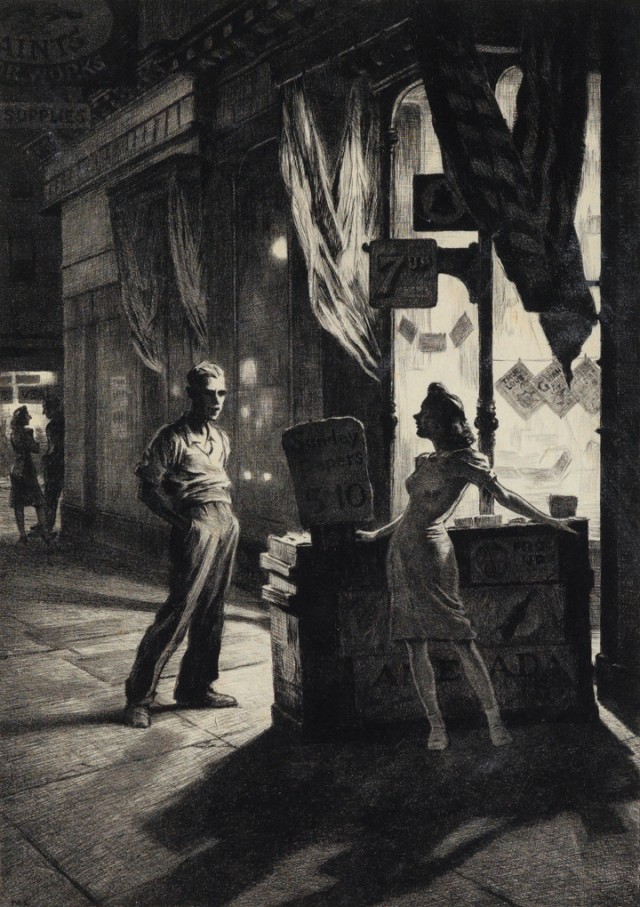

But do you know their sonsaengnim, the generations of Korean filmmakers who went before them? Now you can, no matter where in the world you are, on the Korean Film Archive’s Youtube channel. There, at no charge, you can experience decades of Korean cinema and hundreds of works of Korean cinematic art, including but not limited to those of mid-20th-century masters like Kim Ki-young, Im Kwon-taek, and my personal favorite Kim Soo-yong, director of haunting, even brazen pictures of the 1960s and 70s like Mist and Night Journey.

I actually met the then-octogenarian Kim Soo-yong a few years ago, when he called me over to his table out of curiosity about what a foreigner was doing at a screening of Mist. It happened at the Korean Film Archive’s cinematheque (known as Cinematheque KOFA) here in Seoul, where I’ve lived for the past few years. During that time I’ve also been writing a Korea Blog for the Los Angeles Review of Books, which occasionally features essays on the classic Korean films made available online by the Korean Film Archive. I began the series with Night Journey, and more recently have written up pictures like the 1960s neorealist cry of agony Aimless Bullet, the 1970s college-under-dictatorship comedy The March of Fools, the 1980s Westernization comedy Chil-su and Man-su, the 1990s food-sex-horror satirical mixture 301, 302, and others.

If you need more suggestions as to where to start with the KOFA’s more than 400 free films online, pay a visit to the Korean Movie Database (KMDb), where KOFA regularly post selections from their catalog. This month’s picks are “spy thriller films from the 1950s to 1970s infused with the anti-communist ideology during the time.” Previous months have rounded up “melodramas that are filled with women’s desire and craving for love,” films about “individual or family tragedies leading to historical tragedies,” and “heart-warming classical movies all the family members can enjoy together.” You can watch all these films either on the KMDb (which requires free registration) or on KOFA’s ever-growing Youtube channel. Either way, as we say here in Korea, 재미있게 보세요.

Related Content:

Martin Scorsese Introduces Filmmaker Hong Sangsoo, “The Woody Allen of Korea”

The Five Best North Korean Movies: Watch Them Free Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.