Only recently has “actor” become an acceptable gender-neutral term for performers of stage and screen.

Prior to that, we had “actor” and “actress,” and while there may have been some problematic assumptions concerning the type of woman who might be drawn to the profession, there was arguably linguistic parity between the two words.

Not so for artists.

In the not-so-distant past, female artists invariably found themselves referred to as “female artists.”

Not great, when male artists were referred to as (say it with me) “artists.”

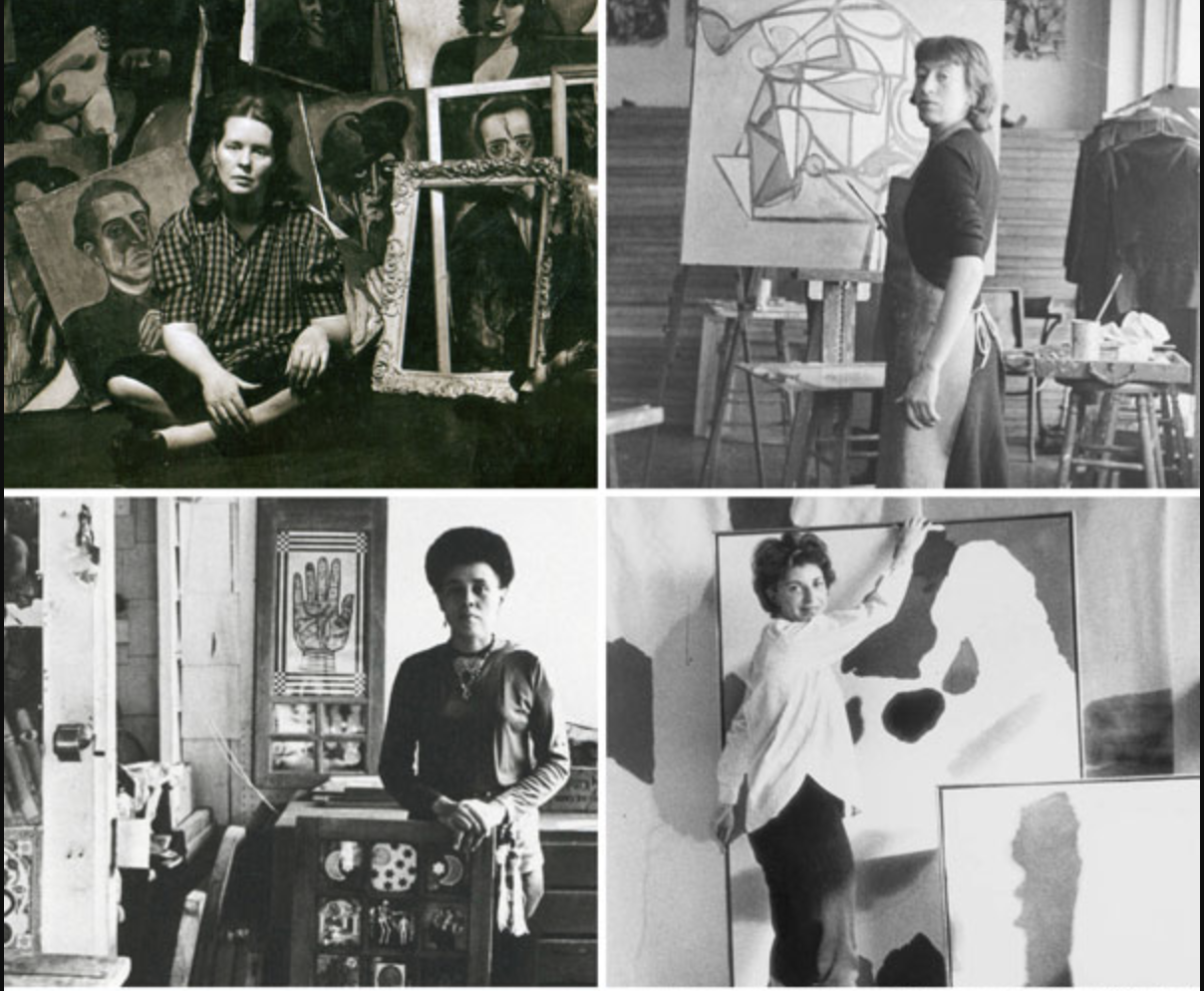

The new season of the Getty’s podcast Recording Artists pays tribute to six significant post-war artists—two Abstract Expressionists, a portraitist, a performance artist and experimental musician, and a printmaker who progressed to assemblage and collage works with an overtly social message.

Hopefully you won’t need to reach for your smelling salts upon discovering that all six artists are female:

and Eva Hesse

Host Helen Molesworth is also female, and up until recently, served as the much admired Chief Curator of LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art. (According to artist Lorna Simpson’s take on Molesworth’s abrupt dismissal: “Women who have a point of view and stand by it are often punished. Just because you get rid of Helen Molesworth doesn’t mean you have solved ‘the problem.’”)

Molesworth, who is joined by two art world guests per episode—some of them (gasp!) non-female—is the perfect choice to consider the impact of the Radical Women who give this season its subtitle.

We also hear from the artists themselves, in excepts from taped ’60s and ’70s-era interviews with historians Cindy Nemser and Barbara Rose.

Their candid remarks give Molesworth and her guests a lot to consider, from the difficulties of maintaining a consistent artistic practice after one becomes a mother to racial discrimination. A lot of attention is paid to historical context, even when it’s warts and all.

The late Alice Neel, a white artist best remembered for her portraits of her black and brown East Harlem neighbors and friends, cracks wise about butch lesbians in Greenwich Village, prompting Molesworth to remark that she thinks she—or any artist of her acquaintance—could have “easily” swayed Neel to can the homophobic remarks.

It’s also possible that Neel, who died in 1984, would have kept step with the times and made the necessary correction unprompted, were she still with us today.

A couple of the subjects, Yoko Ono and Betye Saar, are alive …and actively creating art, though it’s their past work that seems to be the source of greatest fascination.

When New York City’s Museum of Modern Art reopened its doors following a major physical and philosophical reboot, visitors were treated to The Legends of Black Girl’s Window, an exhibition of the 94-year-old Saar’s work from the ‘60s and ‘70s. New Yorker critic Doreen St. Félix bemoaned the “absence of explicitly black-feminist works,” particularly The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, a mixed media assemblage, Molesworth discusses at length in the podcast episode dedicated to Saar.

MoMA also played host to a massive exhibition of Ono’s early work in 2015, prompting the New York Times critic Holland Cotter to pronounce her “imaginative, tough-minded and still underestimated.”

This is a far cry better than New York Times critic Hilton Kramer’s dismissal of Neel’s 1974 retrospective at the Whitney, when the artist was 74 years old:

… the Whitney, which can usually be counted on to do the wrong thing, devoted a solo exhibition to Alice Neel, whose paintings (we can be reasonably certain) would never have been accorded that honor had they been produced by a man. The politics of the situation required that a woman be given an exhibition, and Alice Neel’s painting was no doubt judged to be sufficiently bizarre, not to say inept, to qualify as something ‘far out.’”

Twenty six years later, his opinion of Neel’s talent had not mellowed, though he had the political sense to dial down the misogyny in his scathing Observer review of Neel’s third show at the Whitney…or did he? In citing curator Ann Temkin’s observation that Neel painted “with the eye of a caricaturist” he makes sure to note that Neel’s subject Annie Sprinkle, “the porn star who became a performance artist, is herself a caricature, no mockery was needed.”

One has to wonder if he would have described the artist’s nude self-portrait at the age of 80 as that of “a geriatric ruin” had the artist been a man.

Listen to all six episodes of Recording Artists: Radical Women and see examples of each subject’s work here.

And while neither Saar nor Ono added any current commentary to the podcast, we encourage you to check out the interviews below in which they discuss their recent work in addition to reflecting on their long artistic careers:

“‘It’s About Time!’ Betye Saar’s Long Climb to the Summit” (The New York Times, 2019)

“The Big Read – Yoko Ono: Imagine The Future” (NME, 2018)

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, February 3 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates New York: The Nation’s Metropolis (1921). Follow her @AyunHalliday.