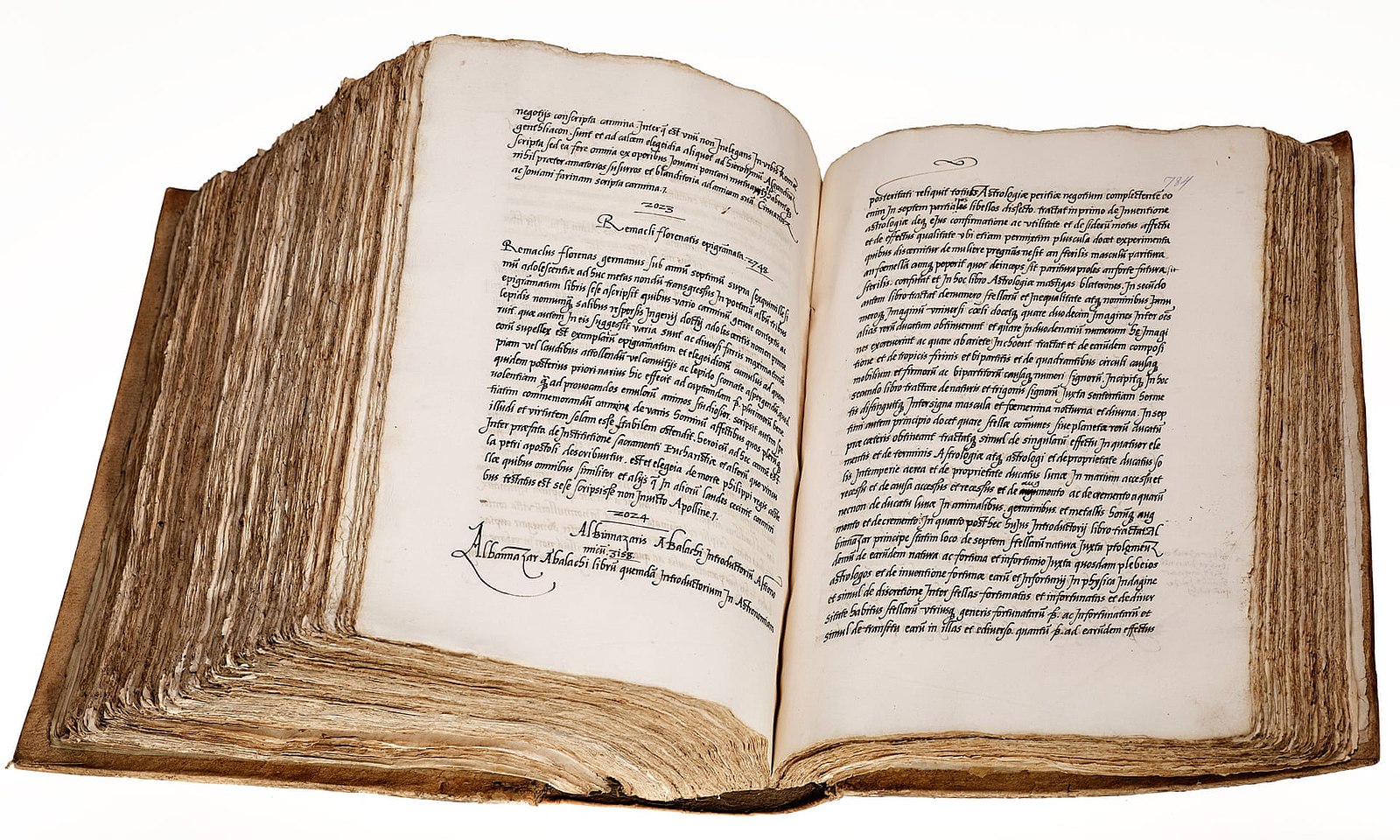

Of the many books released over the past couple decades about the existence or nonexistence of God (and there were a lot) one of the best comes from philosopher and novelist Rebecca Goldstein. Her 2010 36 Arguments for the Existence of God is not, however, a work of popular theology or anti-theology; it is fiction, a satire of academia, the publishing world, the Judaism she left behind, and the bubble of hype that once inflated around so-called “new atheism.”

In a book within the book, Goldstein’s hero, Cass Seltzer strikes it big with his own popular knockdown of religion, The Varieties of Religious Illusion, which ends with 36 refutations of arguments for God in the appendix, which itself provides the appendix for Goldstein’s book. If this sounds complicated, there’s no reason it shouldn’t be. Conversations about God, for hundreds of years the biggest topic in Western philosophy, should not be reduced to syllogisms and stereotypes.

Yet oversimplifying the big questions is what many pop atheist books do, Goldstein suggests. Seltzer’s book arrives when there is “a glut of godlessness” in bookstores. Such books “were selling well,” writes Goldstein, “sometimes edging out cookbooks and memoirs written by household pets to rise to the top of the best-seller list.” The two deep thinkers and religious critics Seltzer self-consciously draws on in his title make his project seem all the more ironically trivial:

First had come the book, which he had entitled The Varieties of Religious Illusion, a nod to both William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience and to Sigmund Freud’s The Future of An Illusion. The book had brought Cass an indecent amount of attention. Time Magazine, in a cover story on the so-called new atheists, had ended by dubbing him “the atheist with a soul.”

By embedding arguments for the existence of God in each of the books 36 chapters, Goldstein implies “the joke—or sort of joke,” as Janet Maslin writes at The New York Times, “is that Cass’s conundrum-filled life illustrates and affirms thoughts of the divine even as his appendix repudiates them.” Dwelling persistently on an idea grants it the very validity one argues it should not have, perhaps.

This does seem to be an effect of certain hard-nosed atheist writing, as Nietzsche recognized very well. “I am afraid we are not rid of God,” he once lamented, “because we still have faith in grammar.” Religious ideas are embedded in the structure of the language; language itself seems to have metaphysical properties. It is like ectoplasm, slippery, opaque, made of metaphors both living and dead. It both enables and thwarts all attempts at certainty.

Goldstein’s creative approach to the God debate stands out for its ambivalence and humor. (See her discuss faith, fiction, and reason with her partner, Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, in the video at the top of the post.) In the compilations here, Goldstein and 149 more renowned academics offer their agnostic or atheist thoughts on God. Some are less nuanced, some lean more heavily on statistics, physics, and math; many come from the theoretical sciences and from analytic and moral philosophy. Some are sympathetic to religion, some are contemptuous. A wide breadth of intellectual perspectives is represented here.

Yet other than Goldstein and a handful of other prominent women, the selections skew almost entirely male (rather like the characters in most religious scriptures), and skew almost entirely white European and North American. We can do what we like with this information. It should not prejudice us against the finest thinkers in the compilation, which includes several Nobel Prize winning scientists, famous philosophers, Richard Feynman, Oliver Sacks, and Noam Chomsky, as well as a few figures who have recently become infamous for alleged sexual harassment, racism, and far worse.

But we might wish the less engaging contributors to this discussion had given way to a greater diversity of perspectives, not only from other cultures, but from the arts and humanities. On the other side of the coin, we have a smaller list of 20 Christian academics addressing the question of God, below. These include respected scientists like Francis Collins and John Polkinghorne and many well-regarded (and some not so) Christian philosophers. The lineup is entirely male, and also includes an apologist accused of faking his academic credentials and an apologist turned right-wing propagandist who was convicted and jailed for fraud. At the very least, these details might call into question their intellectual honesty.

Here again, maybe some of these selections should have been better vetted in favor of the many women in philosophy, theology, science, etc. But there are voices worth hearing here, from professing intellectuals who can keep the questions open even while in a state of belief, a skill even rarer in the world than in this collection of Christian scientists, scholars, and apologists.

Related Content:

Atheism: A Rough History of Disbelief, with Jonathan Miller

Does God Exist? Christopher Hitchens Debates Christian Philosopher William Lane Craig

In His Latest Film, Slavoj Žižek Claims “The Only Way to Be an Atheist is Through Christianity”

Atheist Ira Glass Believes Christians Get the Short End of the Media Stick

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness