No matter the strength of particular beliefs, or disbeliefs, religions of every kind are all equally fundamental to the human experience. This was so for thousands of years before the advent of the world’s big five religions, and for thousands of years after. “Religion has been an aspect of culture for as long as it has existed, and there are countless variations of its practice,” says Episcopal priest and anthropologist John Bellaimey in the TED-Ed video above. “Common to all religions is an appeal for meaning beyond the empty vanities and lowly realities of existence.”

Religions particularize a set of archetypal human responses to universal metaphysical questions like “Where do we come from?” and “How do I live a life of meaning?” and “What happens to us after we die?” Such questions find answers outside the boundaries of religious faith. For an increasing number of people, science and secular philosophy offer comforting, even beautiful naturalistic explanations. And millions more feel the pull of intuitions about a higher power or “a source from which we all come and to which we must return.”

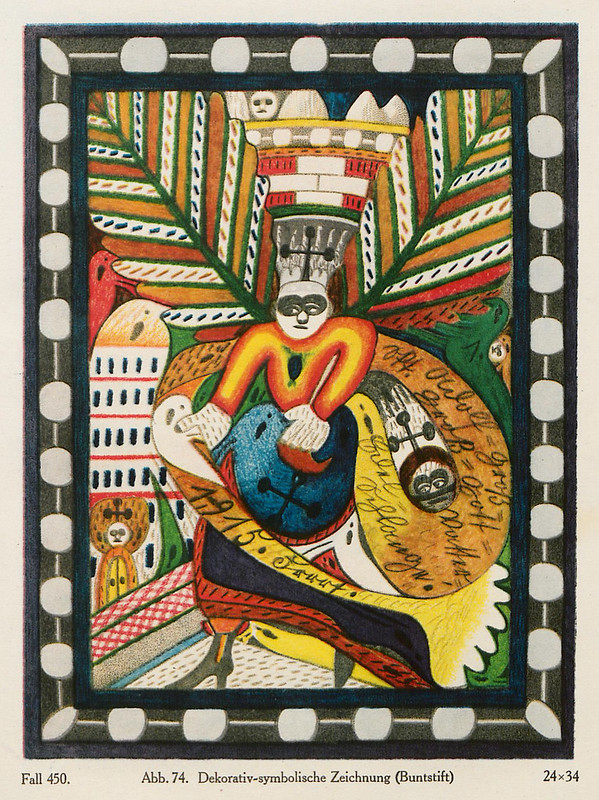

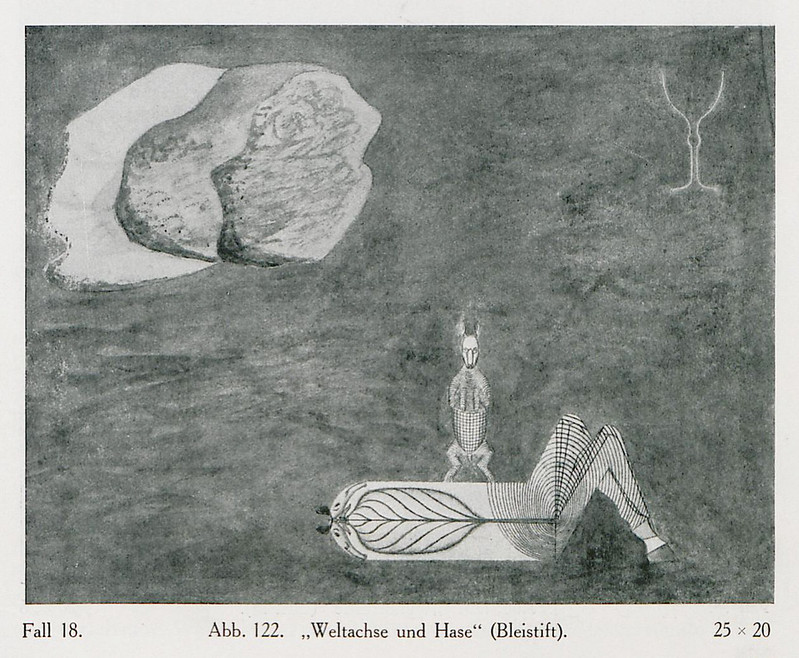

Religion gives the big questions faces and names, of divinities, demons, and holy men (in the five big, it has been almost entirely men). Whether these figures existed or not, their legends shape culture and history and are shaped and changed in turn. Bellamy surveys the big five world religions with an overview of their central narratives, illustrated with montages of religious art. The information is at the level of a 101 course introduction, but the number of people in the world who know little to nothing about other religions is likely quite high, given the numbers of people who know so little about their own. We can probably all learn something here we didn’t know before.

Bellamy’s approach broadly suggests that what matters most in religion is story. But to dismiss religions as “just stories” misses the point. Purely at the level of narrative, we can think of religions as creative ways to tell the stories we find untellable. This says nothing about religion’s effects on the world. Is it a force for good or ill? Given its role in every stage of human cultural development, both positive and negative, maybe the question is unanswerable. There are too many varieties of religious experience over too great a span of time to reckon with.

Bellamy’s charitable explanations of the major five religions highlight their contingent nature—he locates each faith in its particular time and place of origin. But he also shows the universalizing tendencies of each tradition, qualities that made them so portable. He does not, however, mention that more inclusive interpretations usually came from revolts against more limited original designs. Religions and cultures evolved together, materially and culturally. As they spread and occupied more territory with wider populations, they grew and adapted.

In his book The Tree of World Religions, Bellamy develops such historical material into an exploration of twenty world religions from Hinduism to Rastafarianism, showing each one as a collective act of storytelling. Compiled from a 25-year high school world religions class Bellamy taught, the book covers the Mayans, the Norse, and Socrates, Laozi, the Hebrew Prophets, and the Buddha. In what Karl Jaspers called “the Axial Age,” writes Amazon, these later sages “moved religion from mostly-supernatural to mostly-humanistic, shifting the focus on God’s inscrutable otherness to God’s increasing insistence on ethical behavior as the highest form of worship.”

Related Content:

A Visual Map of the World’s Major Religions (and Non-Religions)

Christianity Through Its Scriptures: A Free Course from Harvard University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness