The Internet has redeemed graduation season for those of us whose commencement speakers failed to inspire.

One of the chief digital pleasures of the season is truffling up words of wisdom that seem ever so much wiser than the ones that were poured past the mortarboard into our own tender ears.

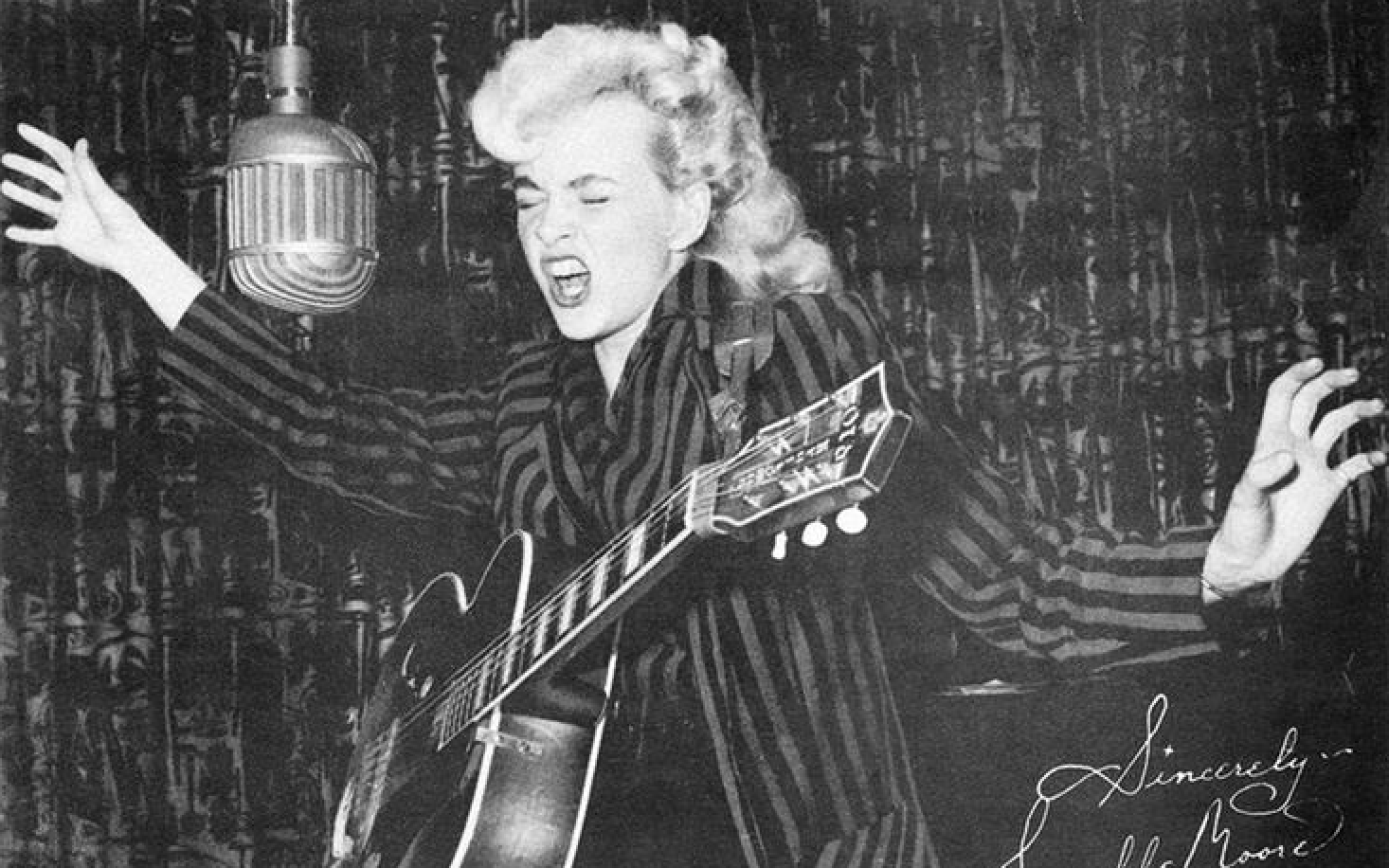

Our most-recently found pearls come from the mouth of one of our favorite dark horses, musician, producer, and multimedia pioneer Todd Rundgren, one of Berklee College of Music’s 2017 commencement speakers.

Rundgren claims he never would have passed the prestigious institution’s audition. He barely managed to graduate from high school. But he struck a blow for lifelong learners whose pursuit of knowledge takes place outside the formal setting by earning honorary degrees from both Berklee, and DePauw University, where the newly anointed Doctor of Performing Arts can be seen below, studying his honoris causa as the school band serenades him with a student-arranged version of his song, All the Children Sing.

Rundgren’s outsider status played well with Berklee’s Class of 2017, as he immediately ditched his ceremonial headdress and conferred some cool on the sunglasses dictated by his failing vision.

But it wasn’t all opening snark, as he praised the students’ previous night’s musical performance, telling them that they were a credit to their school, their families and themselves.

His was a different path.

Rundgren, an experienced public speaker, claims he was stumped as to how one would go about crafting commencement speeches. Rejecting an avalanche of advice, whose urgency suggested his speech could only result in “universal jubilation or mass suicide if (he) didn’t get it right,” he chose instead to spend his first 10 minutes at the podium recounting his personal history.

It’s interesting stuff for any student of rock n roll, with added cool points owing to the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame’s failure to acknowledge this musical innovator.

Whether or not the Class of 17 were familiar with their speaker prior to that day, it’s probable most of them were able to do the math and realize that the self-educated Rundgren would have been their age in 1970, when his debut album, Runt, was released, and only a couple of years older when his third album, 1972’s two disc, Ritalin-fueled Something/Anything shot him to fame.

After which, this proud iconoclast promptly thumbed his nose at commercial success, detouring into the sonic experiments of A Wizard, a True Star, whose disastrous critical reception belies the masterpiece reputation it now enjoys.

Rolling Stone called it a case of an artist “run amok.”

Patti Smith, whose absolutely mandatory Creem review reads like beat poetry, was a rare admirer.

Did a shiver of fear run through the parents in the audience, as Rundgren regaled their children with tales of how this deliberate trip into the unknown cost him half his fanbase?

How much is Berklee’s tuition these days, anyway?

Autobiographical urges from the commencement podium run the risk of coming off as inappropriate indulgence, but Rundgren’s personal story is supporting evidence of his very worthy message to his younger fellow artists :

- Don’t self-edit in an attempt to fit someone else’s image of who you should be as an artist. See yourself.

- Use your art as a tool for vigorous self-exploration.

- Commit to remaining free and fearless, in the service of your defining moment, whose arrival time is rarely published in advance.

- Don’t view graduation as the end of your education. Think of it as the beginning. Learn about the things you love.

Related Content:

John Waters’ RISD Graduation Speech: Real Wealth is Never Having to Spend Time with A‑Holes

The First 10 Videos Played on MTV: Rewind the Videotape to August 1, 1981

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City this June for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.