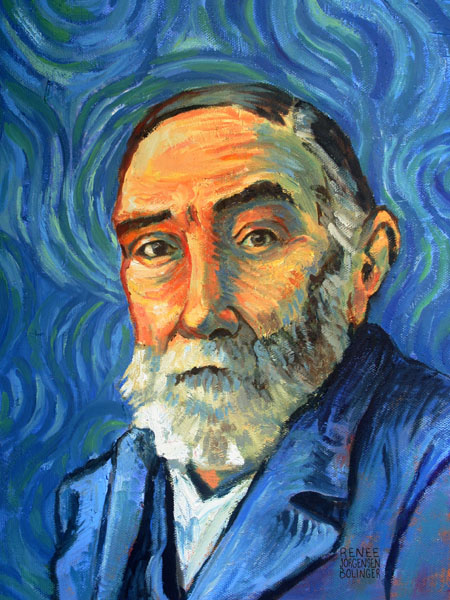

I guess it’s easy to be “The Quiet One” in The Who when surrounded by a preening singer with golden locks, a guitarist with a windmill arm who smashes his equipment, and a completely insane drummer (on and off stage). But John Entwistle helped root the band by standing still and delivering some of the meatiest and beatiest licks and melodic runs in ‘60s rock.

The above footage salvaged from the doc The Kids Are Alright shows the master at work. “Won’t Be Fooled Again” isn’t known as a bass-forward song, so this isolated track from a live take show will make you hear it anew. Entwistle plays his bass like an electric lead, doubling the drums sometimes, other times mimicking the vocals. He plays triplets and runs. He zooms up the neck, slides down, arpeggiates, the lot. It’s thick. Just hit play.

As some YouTube wag points out, it’s something of a bass player joke come to life at the end, where Entwistle leaves his bass onstage and walks off, while a girl rushes out of the audience to embrace the lead singer. Such is life in a band.

From the same shoot, you can also check out his isolated bass from “Baba O’Reilly.” Entwistle has a three-note riff to work with. He stays true to it while filling in spaces here and there with distortion turned way up. At the end he has a sip of (I assume) water and looks about as excited as when he started.

In the mid-nineties, Entwistle was interviewed for a book on drummer Keith Moon. Author Tony Fletcher caught him in an honest mood:

“I wasted my whole fucking career on The Who,” he said between gulps of Remy Martin brandy, his favourite tipple. “Complete fucking waste of time. I should be a multi-millionaire. I should be retired by now. I’ll be known as an innovative bass player. But that doesn’t help get my swimming pool rebuilt and let me sit on my arse watching TV all day. I wouldn’t want to, but I’d like the chance to be able to.”

Not all rock bands consist of best friends, and some are downright rancorous. But that’s often what brings out the best in people. So as you gaze at Entwistle stifling a yawn during these two clips, consider his confession and enjoy.

Related Content:

The Neuroscience of Bass: New Study Explains Why Bass Instruments Are Fundamental to Music

Listen to Grace Slick’s Hair-Raising Vocals in the Isolated Track for “White Rabbit” (1967)

What Makes Flea Such an Amazing Bass Player? A Video Essay Breaks Down His Style

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.